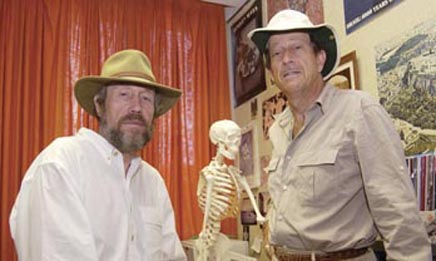

Epidemiologist DeWolfe Miller, left, and historian Robert Littman

A Mummy’s Tale

A donkey stumbles in the Sahara Desert, launching two University of Hawai'i at Manoa professors on what may be the most significant archeological find in Egypt in half a century

Near the Bahariya oasis, 260 miles southwest of Cairo, lie the tombs of approximately 10,000 mummies, until recently hidden beneath the desert sands. These mummies represent a span of about 600 years, from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD, a timeline that covers both the Greek and Roman conquests of Egypt. Unlike the residents of royal tombs in famed pyramids, these mummies come from all strata of society—the rich, the poor and the middle class.

During summer 2002, DeWolfe Miller, a professor of epidemiology, and Robert Littman, a professor of classics, made a preliminary survey of the Bahariya oasis. Accompanied by Manoa students, they worked out the logistics for a three-year project that will begin in 2003. Miller has worked in Egypt for about 25 years on the control of parasitic and infectious diseases. Littman is a historian specializing in ancient medicine. He also teaches a class on Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Tombs of the common people

"There’s never been such a large find of a series of tombs," Miller says. "There are so many mummies. Now we have a window into the past of health and disease among the Egyptian population." The records of Pharaohs’ lives decorate the walls of their elaborate tombs and reside in ancient texts. For the majority of ancient Egyptians, however, documentation is scarce. The mummies of Bahariya present an almost unheard of opportunity to systematically examine a substantial cross section of the society. "This will answer questions about the health and disease of a pre-modern population more than anything that’s been done in the last several hundred years," Littman says.

Leading the expedition is Zahi Hawass, chair of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities and internationally renowned as the premier authority on Egyptian archaeology. Hawass discovered the Bahariya mummies in 1996 after a donkey tripped on a tomb. Littman and Miller will work with the council’s leading archaeologists, conservators and excavators. The two professors have also assembled a team of researchers including Egyptologists, paleopathologists, epidemiologists, bioarchaeologists, radiologists and physicians.

CAT scanning the mummies

The team plans to use a portable CAT scanner to examine 300–500 mummies. The CAT scan will provide a detailed picture of the body without disturbing the wrappings. Researchers will have a complete, three-dimensional view of the mummy itself, including the entire skeletal system. "This kind of technology will allow us to peer into the body and look at all the clues as to the disease processes going on at the time of death or disease processes that might have occurred and then healed," Miller explains.

Miller and Littman hope to also use the CAT scans to reconstruct facial features, in a process similar to the reconstruction of King Tutankhamen’s face on a CNN broadcast this past summer. "We’ll be able to do a much better job using three-dimensional CAT scans," Miller says.

The study will allow the team to construct a comprehensive picture of the health and disease of this population. This information will give insights to many other aspects of ancient life—population, food supply, diet, demography, social life and religion.

"It’s going to be one of the most important studies done on mummies in the last 50 years, if not the most important study ever," predicts Littman. "This will put UH on the map in terms of Egyptology and the history of medicine."