Death Fever

Yesterday, I went over to my mom’s house to fix her bathtub drain. “It’s not working,” she told me. I looked from the toilet plunger in the bathtub to the drain, then I leaned over and pushed the lever down. The water went on its way.

“Well, it’s not going very fast,” she said.

“It’s going fine, Mom. Why don’t I look at your bills, since I am here.”

Halfway up the stair, she sat down. This is a gesture of the women in my family, confidences in stairwells.

“Give me your word,” she said. Her voice was tremulous, her breath ragged. She read the question in my face. “Give me your word you won’t lock me up.”

“I won’t, Mom, I won’t. But we have to figure out something else we can do when it gets bad.”

“You have no idea what they did to me in there.” She is squeezing her own hands and turning them over each other.

“Nothing like that is ever going to happen to you again, Mom. You have a family that supports you.”

“But what will happen? Can we get some pills?”

“No, Mom, you’re not entitled to the Death With Dignity prescription.”

“Why not? I’ve already received a life sentence.”

“Because of the way the law is written. It says you have to be six months from the end of your life as determined by a physician and also in your right mind.”

“And by the time I get that far, I won’t be in my right mind.”

“Right.”

“Well, that’s rotten.”

“It is. It makes me angry. The only legal option is Voluntarily Stopping Eating and Drinking.”

“How long does that take?”

“Seven to ten days.”

“How ghastly. I want to go quick.” Then she is crying. “I don’t want to lose who I am.”

I realized my mother was changing this winter when the first heavy snow hit, weighing down the lines and taking out the electricity. When I called, I learned that my mother had no lanterns and no snow tires on her car. She also needed new boots. She came out into the snow wearing clogs and managed to navigate her way down the stairs to the parking lot. In the store, while she was trying on boots, she kept changing places, moving from one bench to another while I zigzagged across the floor, collecting our purses and shopping bags.

“I’m like Mr. Magoo,” she said, when she realized.

“You’re not allowed to move again,” I said, dumping our purses. We laughed.

Does anyone know who Mr. Magoo is anymore? His main problem as a comic-book character was short-sightedness, which he refused to admit he had, even as it got him into one amusing predicament after another. He seemed always to be saved by a stroke of luck, unscathed and oblivious. I wish the same for my mother. But I picture her future brain, the deposits of proteins like the snow weighing down the electric lines, the world preternaturally quiet and stark, the hum of everything in our houses stopped.

My eighty-four-year-old mother is at her best on a trail and keeps a pretty good clip in her hitched gate—two hip replacements later. We walk alongside the Nooksack River, around us the thronging green of new spring. At the bank, she remembers her father teaching her to fly fish. From the way she gazes at the glinting water, I wonder if she sees him there. The next day, she thanks me again for taking her. “Let’s go back to the desert soon,” she says. The river roils with new run off. I am seeking the headwaters of this story.

As a girl, my mother felt most herself in a horse stable, mucking out a barn. Her father owned a cattle ranch in the Ventura hills, Running Springs Ranch. Pepper trees lined the drive. She took me there when I was a child, before the tract home developers shaved away all recognizable topography. She remembers the name of her first horse: Tickle. She still walks her dog a mile or two every day, even when her vertigo is so bad she thinks she might fall down. We meet to walk to the dog park in Sudden Valley, near the old red barn that is all that remains of the cattle ranch this place once was. The golf course lies in a gentle basin bounded on one side by a nine-mile lake, and on the others by foothills and forests. She’s slender and walks fast, forward tilted. When she is a certain distance from me, she looks like a girl, and I feel a wistful anguish as though I could see the working ranch of her childhood from here or as though she could have seen this former ranch when she was a girl, this place where she will choose to die.

We’re at the breakfast table on a Sunday with my brother when my mother says to me, “I saw you talking to my doctor.”

“Mom, I haven’t even met your doctor. You have an appointment next week.”

“No, I saw you at the cocktail party. You were talking to him.” She sounds none too pleased.

“Mom, we’re in a pandemic. I’ve never been to a cocktail party with your doctor.”

“Maybe it was a dream,” my brother suggests.

“Maybe,” she says, not sounding convinced. “It felt real.”

I don’t believe my mother has trusted anyone since she met my father.

She was in her third year at Stanford studying art history. He was a Catholic boy on scholarship, son of a widow, studying pre-med. She was an upper-class Protestant, and back then their match was considered a cultural crossing. Though she lives in a small condo now, my mother grew up a debutante in a 1929 brick Georgian house in mid-Wilshire Los Angeles. When I watch the film version of Little Women with my mother, we spot pieces of her furniture: the horse hair chair with the spiral arms, the walnut chest with its sculpted fruit and nut handles, the oil painting of a stately quarter horse. My father’s beauty as a young man was piercing—the plush curvature of his mouth—and I imagine my mother associated it with sorrow, or maybe shame, something recessed in him she wanted to touch. His mother, Haydèe, was a New Orleans creole who found work at the unemployment office because she was fluent in both Spanish and French. Haydèe confessed to my mom that for years, instead of going to mass, she dressed up and went to Dunkin Donuts. Even later in life, my father’s distaste for the church in which he was raised was pronounced, more like revulsion than distaste, more like fury. He once pointed to my son who was six and said, “Imagine being a boy like that, like that, and being threatened with fire and brimstone.”

I believe a sin was committed against my father early in life. Perhaps it happened at Loyola Catholic School for Boys or at his local parish. I believe it’s the reason my grandmother quit going to mass, quit making her boys go. I’ll never be able to verify if he was abused though both my brothers think so, too. My father was covert in his actions. Once he flew up to Seattle from San Jose without telling any of us and dropped in on my brother at the office because he was angry. My father liked stealth.

I have no compass points for the truth from my parents. I do know that when my father left his third wife, she told me he had already rented and furnished an apartment without telling her. Unprocessed trauma plays out as pattern. That’s why this story loops like a lariat in a rancher’s hands, a circle in the air first and then a circle in the dust.

My mother cries when she tells me this story: “After I was released from the hospital, I went to the house where you and your father lived, except it was empty. I stood there, looking through the windows. I didn’t know where he’d taken you.”

“I don’t want you there when I speak to the doctor.” My mother’s tone is arch. “I am perfectly capable of handling my affairs myself.”

“Mom, you have a disability now. Short term memory loss is a disability. You can learn to compensate.”

“I do. I write everything down in my calendar.”

She does write everything down in her calendar. And then she gets mixed up and whites it out. Then she says she can’t use the white out tape. It’s not made for left-handed people. She gives it to me. I spin the loop back in and take it home. We buy her bottled white out. She says it makes her wheeze. What she needs now is white out tape. Some pages of her calendar are so covered in white out, I can’t see the date.

“I’m not going to take over your doctor’s appointment, Mom. I am just going to be there as your co-pilot, as your auxiliary memory.”

“I don’t want to be useless.”

“You’re not, Mom. We’re all making adjustments.”

She is abruptly tearful. “I’m so sorry. I am so sorry for what this is doing to your life.”

I almost prefer her fighting with me or blaming her memory loss on the pinched nerve in her neck, prefer it to this torment, this floodplain of grief.

I think about traumatic brain injuries now that my mother is losing memory and cognition. In high school, my mother had a ski accident that concussed her, and she lay in the hospital for weeks while the cortisone dissolved the clots in her brain. This morning, she called to tell me she didn’t need to see the neurologist.

“I only lose my memory when you put pressure on me. You’re so bossy.”

“Blaming me is not going to help, Mom. This has been going on for a year.”

My mother and I have resolved to look through the photo albums this summer, so I can annotate them for my kids. One afternoon, we are leafing through the album from Germany, where my father was transferred by the army to treat soldiers diagnosed with syphilis and deliver the babies of officers’ wives. She says quite matter-of-factly, “There’s your father’s lover.” I peer closer, a dark-haired woman no less vixen than my blonde mother.

My mother was supposed to stay stateside with us— I was six months old and my brother was two— but within weeks, she grew restless and decided to join him. She maintains that my father picked her up at the airport with a woman named Annaliese, his new friend, and that my mother had to sit in back with us. Maybe he borrowed the woman’s car. Maybe not. According to my father, Annaliese became pregnant after an affair with a senior officer. My father confronted him in order to make the man do the right thing and support the child. According to my mother, my father was having an affair with Annaliese and the baby was his. Either could be true. Dr. Trueblood certainly liked to be the hero for women. He was also very principled and stood his ground. Later in life, when he was chief of staff at El Camino hospital, he publicly posted the C-section rates of all the obstetricians until the numbers fell.

“After Dad died, I found handwritten letters from Annaliese,” I say. I don’t hasten to turn the page. “And pictures of her daughter under his bed. The child certainly didn’t look like Dad.”

My mother shrugs. “The art of innuendo,” she says. “Your brother doesn’t look like him either.”

If there were love messages in those letters, they were couched in “remember when’s.” Scenes of ice skating and leaves falling. Prosaic. Naturally I was hoping for something definitive. And I only found a handful of letters …though she wrote to him for nearly twenty years. You decide which version of the story you like best.

I don’t like either.

We lived in the village and my mother drove a Volkswagen with walnuts in the tire treads for traction on the snow. By accident, she drove through a tank squadron and the ground shook. There’s a fetching picture of us as a family from that time—my father and brother in lederhosen wearing felt hats with jaunty feathers, my mother and I in our dirndls. We had friends in a farm house, mulled wine, Krampus at Christmas to chase the children around. He was Santa’s devilish sidekick. We screamed and ran while he roared. My grandparents hired my mother a housekeeper who waxed the floor with mayonnaise, and we all slipped and fell. To amuse himself, my brother lit toilet paper on fire while sitting on my parent’s bed. My father came home to a mattress smoking in the snow; my mother had managed to shove it out the window. Towards the end, my mother confronted my father about the alleged affair. It seemed he was always gone, and so stony when he was home. He denied the liaison, saying it was all in her head. “He was God, judge, and jury,” as she puts it. When he left that weekend for a hunting trip, she took us to the farmhouse neighbors, then took all her sleeping pills and lay down.

My father arrived home early and saved her. She was medevacked back to the states in a Red Cross helicopter. He would follow later on a military flight that dropped us off in Philadelphia, where my father boarded a train and rode with us to Los Angeles, his two children aged four and six.

Years later, when I told my father that my mother believed he had had an affair in Germany, he said, “I can see why she might have believed that, but it’s not what happened.” I remember exactly where we were when we had this conversation because he did not look at me as he spoke. We were standing at the western edge of the university campus where I teach, eyes traveling from the dark teal blue of the Puget Sound to the glittery peaks of the Coast Mountains in Canada. “She was the one who ran off to Vienna to have an affair with a sculptor.”

The next time I spoke with my mother, I asked her about it. She said, “Oh, that. That was only after his affair.”

Today, she taps her finger on a photo I cherish: the four of us on a blanket at the beach, my mother’s heavy hair swept up in a French twist, a tender cast to my father’s face, their babies lolling about in their laps. Evidently, my parents’ fights were epic: “I tried to scare him,” she says now, “and I guess I succeeded.”

After the suicide attempt, she wound up in Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital, and it would take her parents and lawyers to get her back out.

The young neurologist asks my mother if she has ever gotten lost. “Yes, I did once, in the car.”

“And what did you do?”

“I just drove around until I recognized something.”

This is news to me. He has her fill out pages of questions. She draws shapes, erases them, redraws them. She looks at me. “Don’t ask me to do geometry, Mom.” We laugh. “I can’t help you there.” His walls are hung with enlargements of Mt. Baker and the Twin Sister peaks. For a moment, I feel dug in at the summit, bivouacked where the air is thinnest. After the tests, he tells her he thinks she has a major dementia syndrome developing.”

“But I feel like myself. Are you sure?” she says.

“There is no doubt in my mind, from the tests and what you have told me, that there is a major dementia problem going on.”

With great kindness, he asks her to stop driving. “I wish there was some way for you to maintain your independence.”

“I’ll only drive to town and back,” she says.

He’s ready for this. “I’d recommend that you get a behind-the-wheel test at the DOL. They do them for seniors. I have to ask that you not drive until that’s done, and the office may not be offering the tests yet because of the pandemic.”

He mentions blood tests, MRIs, and medications to boost the brain chemicals for improved memory.

She cuts through his medical-ese: “Does it just get worse and worse until you’re no longer a person?”

No,” he says, “You’ll always be a person, you will just need more help, eventually a full-time caregiver. But that progression is five to ten years. Once you come to terms with this terrible news, you’ll realize you have lots of quality of life ahead. You don’t live in pain, and you are capable of joy. We all get a dementia of some kind in the aging process.”

My mother squints at him. “I fear being controlled.”

“There are entire organizations to support you,” he says, smiling.

While my mother pays the copay, I roll up brochures full of senior care options, and breathe the heated air inside my mask. On the one hand, I am grateful to this doctor for his positive outlook, and on the other, I think, buddy, you’re ducking it. I’ve read about what end stage Alzheimer’s looks like: intelligible speech lost, ambulatory ability lost, ability to sit up lost, ability to smile lost, ability to swallow lost…

She and I are stunned and silent going down the stairs from the neurologist’s office—my mother always takes the stairs. In the car, I propose we get a milkshake, an old family tradition in tough times, except we don’t know what’s open in our town anymore. Eventually, I find a smoothie shop. There are instructions on the door for ordering from an app or via the website. I can’t make the website work, and I don’t need a free app on my phone to gum it up with advertisements. I can see two young women inside running the juicers. Finally, I just call the shop’s number and ask if I can order. We wave through the window.

Back in the car with my Mahaolo Mango and her Pina Koolada, we suck in some sweetness. After a few moments, my mother rests the cup in the holder and turns to me. Her blue eyes pool with fear. “I won’t go into one of those places,” she says, her voice running out with her breath. It takes me a moment to realize she isn’t talking about the smoothie shop. She takes a deep quaking lungful of air. She means assisted living or a nursing home. “I don’t ever want to be locked up. Your father had me committed.”

“I know, Mom, and I know it has made you really afraid,” I say. “But you heard the doctor, we can hire people to help you at home.”

“You have no idea what they did to me in there. And your father colluded with the doctors not to let me out.”

“Mom, that’s not what is happening now. We’re going to make every decision together.” But she is not hearing me. The sound of pain in her ears must be like the rail squeal of a mile-long freight train. She clutches my hands.

“Promise me,” she begs, “ promise me, you’ll never lock me up.”

“Mom, I’d rather die than live in a nursing home. My friend Carolyn lived in one.”

“Me, too,” she says. “I’d rather die.” She sighs and looks out the window.

“I’ve been afraid tell you that.”

“You shouldn’t be. It’s a relief to hear it said.”

“People choose to voluntarily stop eating and drinking, Mom, so they can stay at home. It’s kind of a movement.”

“That’s what I want to do then. When it gets bad. I want to stay in my home.”

“I learned about it a few years ago, Mom. My church was sponsoring a workshop, and I went to it.”

“Why would you do a thing like that?”

“Because I thought this day might come.”

“Oh sweetheart. You are so courageous.”

As a young woman, I tried to understand what had happened to my mother at Langley Porter. At U.C. Berkeley, where I went to college, I read feminist critiques of the male-dominated and male-defined mental health system, and the histories of women who had been institutionalized. In Women and Madness, Phyllis Chesler asserts that “Women who reject or are ambivalent about the female role frighten both themselves and society so much that their ostracism and self‐destructiveness probably begin early.” My mother received electro-shock and Thorazine, I know that much. Following her release from Langley Porter, she divorced my father and won custody of us in a courtroom. When I see her walking toward me with her lilting gait and her girlish wave, I think of the courage it took to fight for us, and how exceptionally close it made us— my mother, brother, and me. My husband thinks we are a volatile family emotionally, and it’s true, we go the mat with each other. We shout a lot but we also show up for each other; we hear each other out. I believe my mother trusts only us in the world. She is like an electrical storm, beautiful and terrifying. There is something so solitary and brave about her. How else could a person make the decision to voluntarily stop eating and drinking?

My mother still likes training dogs on agility courses and in the mornings when we walk, she makes her foxlike Shiba Inu bounce back and forth over a hanging chain or walk along a log. She likes the single-mindedness of animals. After she got custody of us, she moved us in with our grandparents and took to jumping horses and hanging out with journalists who were shooting a documentary about the Ku Klux Klan in the South. She flew off a dressage horse as it went over a jump. As with the ski accident, momentary flight followed by major crash landing seemed to be the theme. She was in Louisiana with a journalist and Nieman Fellow who was in love with her; also his best friend, who was in love with her, and married. The two men had a shouting match over her hospital bed where she lay with a concussion. There was a commercial airline strike at the time, and my grandfather, who was constantly getting her out of scrapes, arranged for a flight out of Louisiana. The seriously boozing journalist secured a private pilot to fly her to Atlanta. My mother swears the pilot’s name was Monkey Scales and that he could not read the instruments. Every so often they’d swoop down over the Interstate to read the highway signs. He crash-landed, and it’s never been ascertained if that was what concussed her again or the riding accident. I remember visiting her in the hospital. She wanted me in bed with her, and she let me have her chocolate pudding. Strands of light came through the slats of the shutters, glistening like fishing line, and I knew even then, if you put my mother to the test, she could pull more than her own weight.

My mother’s doctor is Polish, somewhere in his mid-sixties, which means he graduated from medical school in Poland in the 1970s, emigrated here, learned English, and completed medical school a second time. Under “personal interests” on his doctor profile page, the first thing he lists is “family.” Also, “boating, ham radio and Coast Guard Auxiliary.” He speaks English, Polish, Italian, and German. I followed the advice that Kathleen at Compassion and Choices in Seattle gave me and called the doctor’s office first to find out if he would be willing to support VSED medically, so we could avoid an uncomfortable exchange and the doctor could prepare… or not. His nurse called back to say we should make an appointment. The doctor would talk to us about Voluntarily Stopping Eating and Drinking.

We wait a long time in the examining room because while he is appreciated for his thoroughness and attentiveness, his patients also know this means he runs chronically late. In the examining room, my mother’s blood pressure is high. She asks to take her black cloth mask off and is told not to. She turns to me, “I feel like I can’t breathe in this mask. It’s so thick. I’m claustrophobic.” I ask the nurse if we can have a paper one.

Dr. Zieliński enters the room in a big way; evidently a big and blustery guy—“Hello Sara, how are ve doink? You don’t look like a person who is dyink. You look very nice, as alvays.”

“Well,” I’m not dying,” my mother says, brightening noticeably, “but I do want to talk about end of life issues.”

“If you vant to talk about end of life issues, you vill have to convince me you are dyink,” he says, gazing at her with a soft smile. I suddenly remember coming across a poem on my mother’s computer filed “For Dr. Zieliński.”

“I’ve had this recent diagnosis.” She can’t seem to summon the word Alzheimer’s. I wonder if she is panicking under the mask. “And I want to know what my choices are… Can I take this mask off?”

“Certainly. Take it off.” He pulls his own mask down beneath his chin and pushes one hip into the counter. He looks like a bald, round-headed baby with a bib under his chin.

“Vat your choices are…vell, nobody has a right to force feed you. That can be honored. Help me understand vat you are seeking.”

“When the time comes, I want to choose to die.”

My mother is perched on the examining table and the doctor is standing. I am sitting in the corner of the room, literally, and their conversation seems to be taking place over my head. I wait for my mother to say the words she came here to say: Voluntary Stopping Eating and Drinking, or even the abbreviation, VSED.

“I don’t do euthanasia, Sara. The drugs that bring about death are controlled substances by the federal government. I don’t vant to go to prison. I tell my vife, if I am in a really bad shape, take me to the mountains, I vill walk off into the snow. That vill be between me and my maker. In certain religions, you cannot take your life. But every year, so many people drive off the cliff, and these are not recorded as suicide.”

“I don’t want to commit suicide,” my mother says. She looks at me, quizzically, as if to say, what are we talking about? I am no longer sure either but it is becoming clear to me that he may not support VSED. Is he recommending my mother drive off a cliff?

“Listen,” I say to him, “My mother has just been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. She has only this window of time in which to make plans. While she is mentally competent. And she doesn’t want to spend years in a nursing home.”

My mother echoes this, “No, I don’t want to spend years in a nursing home.” She is ready to get back on board.

Dr. Zieliński squints as though he is trying to see us from the other side of the world. “I say, if you get to go to nursing home, if you get to. I took care of my mother and it vas very hard time; my grandmother took care of her sister. Nursing home is luxury.”

My mother is swinging her legs like a girl and looking down at her knuckles.

I try from another angle, scrambling to get my footing. I thought he was going to help us. “What about the vascular dementia? My mother is at increased risk for stroke.”

“If she has stroke, it’s simple,” he says. “Simple.”

I feel my cheeks redden. “My husband’s mother was in bed for eight years after a stroke, disabled and locked in. How is that simple?”

The grey and grizzled doctor sits on his stool so we can better stare at each other.

“Listen, two hundred years ago, you vent how you vent. Too much morphine suppresses breathing center. We, as physicians, are being put at tremendous risk in this litigious country. Government immediately counts any narcotic I prescribe.”

“I understand, but that’s not what we’re asking. There are doctors in Whatcom County who are providing palliative care to patients who choose VSED.”

“I don’t know about that.” He takes off the square yellow-tinted glasses he wears that make him look like a seventies game show host and scrubs at them with his lab coat. “I have malpractice. I let hospice take care.”

“Hospice won’t come in Whatcom County if she chooses to do VSED. That’s why we need a doctor.”

Dr. Zieliński stands and puts his glasses back on. He resumes looking at my mother. “Ve don’t know how things gonna go. Nobody knows.”

“No, we don’t.” My mother raises one shoulder as she says this, a very feminine gesture I’ve known my whole life.

“Your daughter is legally vell-versed. I am not. People do all kinds of things, that is between them and their God. I am not able to completely satisfy what your daughter vants me to do.”

Part of me doesn’t mind the way he has cut me out in order to return the conversation to a one-on-one between them. This is my mother’s doctor after all, and I feel a little bit like a child in time-out watching my parents. Yet another part of me feels utterly dismissed, and worse implicated, as a spoiled American daughter who wishes to duck out on pain and responsibility.

Dr. Zieliński tells his nurse, “Ve going to do a new POLST form,” and when she delivers it on a clip board, he gets to work.

“If you’re in a bad shape, you’re not making these decisions. Ve take measures now. You have dementia, so ve going to say nobody search for cancer, okay?

It takes me a few minutes to remember that POLST stands for Physician’s Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment; it’s the form the medics take off the refrigerator if you’re going on an ambulance ride.

He begins checking off boxes: “No to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. No medically assisted nutrition…”

“Oh, thank you,” my mother says, “yes.”

Don’t be so grateful, I think, and in the same breath, at least he is getting us part way there.

“Sara,” he says, “I have seen bad things. Ven I vas only doctor in my county in Montana, I also act as coroner. This couple, many years disputes between them. The husband, he put couch up against door and rifle under chin, so vife would see him thru front window. Blew his whole head off. I have to see that.”

My mother says, “That was an act of rage.”

Dr. Zieliński nods. “‘Lady,’ I said to this woman. “‘Your husband must hate you, really hate you, to do that.’”

“You have seen such terrible things,” my mother says. They are gazing at each other. I feel like they have forgotten I am in the room.

“Yes, I have seen these terrible things,” he says. In that moment, I see that my mother is someone to whom he has spoken his mind, a person to whom he could speak his mind, these many years. At first, I wonder why he is telling her this story. To let her know he can’t bear to help anyone end their life? In a moment, I have my answer. In parting, he stands right in front of my mother and looks into her eyes. He knows this is goodbye. He has a big face with a small smile in it, and he keeps his teeth hidden, which adds a kind of sweetness to his countenance. And then they embrace…in the middle of a pandemic… the doctor who has a crush on my mother and my mother who has a crush on her doctor. I am embarrassed to be in the room.

In the car, my mom says, “He’s not going to help us, is he?”

I am relieved and impressed that she has pulled the essential information from the exchange.

“No, I think he is Catholic, Mom. That’s the majority religion in Poland.”

“He was very emotional, all over the map really.”

“What was that hug all about?”

She laughs. “I think he has a crush on me.”

“And you have a crush on him! Sheez, Mom, still working your wiles.”

“I felt bad for him. He couldn’t stand the idea of helping me die.”

“He has a good heart, but yeah, he’s not going to help us VSED.”

“When did we become “we”?” she asks.

“Mom, I can’t ever be the one to bring up VSED to a doctor again. That can’t come from me or other people will think I am coercing you. Dr. Zieliński thinks I don’t want the bother of caring for you.”

“That’s so not true. You’re caring for me right now.”

“I know, but you heard what he said about nursing homes.”

“He’s just very conservative, paternalistic. I thought he might be. What next?”

“We need to find you a new doctor.”

That night at home, I ask my husband, the child of Latvian refugees, how the doctor could view walking off into the snow as natural but not voluntarily stopping eating and drinking. “He’s old world,” my husband says. “Starvation is something other people do to you, it’s not something you do to yourself.”

At night, I research, and I talk to my brother. VSED sounds like it can go one of two ways—my mother could lapse into a coma in three days and be gone in six, or it could be a long haul, nine or ten days of shriveling and thirsting while her hands and feet turn blue. For several weeks, I‘m frantic on the internet, fueled by a rash grief: I reach out to Compassion and Choices (formerly the Hemlock Society), and the Final Exit Network, another volunteer organization dedicated to “self-deliverance and assisted dying for the terminally and hopelessly ill.” I learn that the helium hood method is the most popular, and that it is not painful to breathe the inert gas. But there are other problems: my mother would have to do it entirely herself (none of our fingerprints on the hood), although we could be there with her. (It is not technically illegal to watch a person commit suicide.) I also learn that party stores no longer sell pure helium; it’s now 20% air and won’t work for the purposes of departure. One morning, I make an urgent call to my brother: “Can you get pure helium?”

“Yes,” he says, “from welding supply.”

“Just call me Katy Kevorkian,” I say.

I visualize everything, my mother’s brass bed, her terra cotta red chair, the books at her bedside, the brass clock with the black roman numerals. I can’t decide if my brother and I should throw away all evidence of the helium tanks and equipment afterwards (so she won’t be found with a turkey baster bag over her head) and do as Derek Humphrey advises in his book: leave her house and buy something so that there will be a receipt with a time stamp. Then, on the morning of the next day, call the doctor. Humphrey advises against calling an ambulance, which would bring the police. With luck, the doctor and the coroner will deem the cause of death as old age. No autopsy, no investigation. I find no records of assisted suicide being prosecuted, and ours is a right-to-die state. Still, there is a risk here. My mother is adamant we not take any risk. “I’m not going to ruin your lives.” So, I picture leaving her in her bed, beneath the lemony satin quilt, hood on, plastic sucked to her face. That way, it will be clear she did it to herself. The roman numerals on the clock in her bedroom seem to keep time to a different era, a different universe.

“Yes,” my mother says, “but if Andrew is going to buy the helium and bring it here, that’s a problem.” She lets out a huge sigh. “Why can’t I just have pills?”

This I have explained to my mother repeatedly. Physician-assisted suicide is legal in Washington but excludes dementia patients.

“So, I’m screwed,” she says.

“Basically,” I answer.

Next week, we will have this conversation again. I wonder about the role of credulity in her memory. After all, she was hanging out with movie crews during the barbiturate-plenty seventies. She can’t believe phenobarbital and Seconal are that hard to get. She also can’t believe Alzheimer’s is excluded from the right-to-die law when in her view it is a terminal disease. “It just takes forever,” she says to me ruefully. When she forgets why she can’t have the pills again, I will remember that she took sleeping pills once, a long time ago in a far, far away land, at least that is how my child mind framed it, my mother the queen locked in the tower by her husband.

She calls me at 8:30 one morning. Her voice is hoarse and she is gulping air. “I’ve started,” she whispers.

“Started what?” I ask.

“VSED. I’m not going to eat anymore.”

“Mom,” I say, “It’s not something you just do. We’ve got to have a doctor on board in case you need pain medication. We’ve got to get the lawyer to rewrite your healthcare directive.”

“Oh,” she says. She sounds tearful. “Well, I want it to be soon. I look at you kids and at Connor and Eva and my funny little dog. I go walking, and I am so in love with life, this is how I want to leave it.”

“Mom, I’m going to respect whatever decision you make, but let’s get into Dr. Henares first and make sure we have the medical support you need.”

When I hang up, I get a cup of coffee and call a close friend. Her husband is undergoing treatment for Stage IV cancer. I know that recently he has switched from oxycodone to morphine for pain management. In my state of mind, asking for his drug surplus seems only a little bold. I’ve known Lucy since 8th grade—I once went on a road trip with her up California’s Pacific Coast Highway and got so high on hash oil I fell out of her car. After years of underage drinking and our generally reprobate behavior as two jailbait girls hanging out with Viet Nam vets, this doesn’t seem out of bounds. In retrospect, I think I was suffering from death fever, the condition that arises when you’ve never thought much about death before and now you think about it all the time. Lucy was very loving. She said, “Um, sometimes he still needs the oxy for breakthrough pain, but I’ll talk to the palliative care social worker and see if we can get more.” Her tone was squeaky with discomfort, yet also honeyed with concern. “I mean, we want to help your mom out.” I thought about the liability and guilt they would feel—his pills inside my mother’s body, stopping her ticker. I never ask Lucy again, and my having done so does not disrupt our friendship. If anyone could understand and forgive my temporary insanity, it is Lucy.

We have to wait a month to get the results of the MRI back from the neurologist. Unlike us, my mother is able to forget that she may have Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia. Sometimes, she is light-hearted. She calls from the front hall when she comes to dinner, “The ninny is here.” She has forgotten her hearing aids and the pie back at her house. “Bearer of little brain!” Other times she tells me, almost as a warning, “I’m going to live a long time like my mother.” Yes, I think, your body will live a long time, but you brain is dying. Often, she completely forgets the visit to the neurologist and his conviction that she has a major dementia disorder. I have to remind her.

“How do you know?” she says.

“I was there with you, Mom.”

“Was I there?”

“Yes.”

“But how can you be sure it’s Alzheimer’s?”

“It’s in the chart notes he gave us. You put them in a file upstairs.”

“You gave me the chart notes?”

“Yes, I did. Let’s go upstairs and read them.”

When we’re done reading them, she leans back in her chair with the fingers of both hands covering her mouth. Then she drops her hands to her lap, suddenly gasping. “Please don’t lock me up. Please. You have no idea what they did to me in there.”

I take her hands. “Mom,” I say again, “I know what happened to you, but that is not what’s happening now.”

In the days and weeks that follow, I swear she can feel that I am withholding something from her, she can feel all that agitated research I am not sharing. Instead I talk to my therapist about the pros and cons of helium hoods versus VSED. I consider aloud where I can get pills. My therapist and I are on ZOOM and we often bend our heads towards the screen so that I have the feeling we really are putting our heads together. His eyes get fishbowl large. I expect him to favor the legal options, but he says something that squeezes the blood out of my heart. “A body may be barely occupied and still fight for life. It can get very unclear. The memory of it could stay with you for years.” There is no way I want to wonder if I killed my mother.

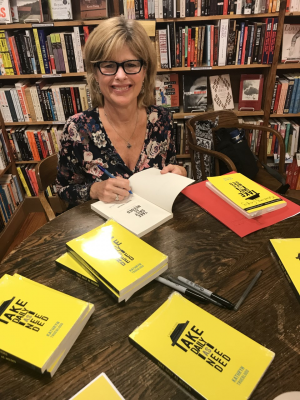

Kathryn Trueblood’s newest novel, Take Daily As Needed, presents the challenges of parenting while ill with the desperado humor the subject deserves (University of New Mexico Press, 2019). She has been awarded the Goldenberg Prize for Fiction and the Red Hen Press Short Story Award. Her work is situated firmly in the medical humanities. Her previous novel, The Baby Lottery, dealt with the repercussions of infertility in a female friend group (a Book Sense Pick in 2007). Her story collection, The Sperm Donor’s Daughter, takes a look at assisted reproduction. Trueblood has offered workshops in therapeutic writing at The Examined Life Conference at the University of Iowa, the Hugo House in Seattle, and the Lighthouse Writers Conference in Denver. Her essay, “Writing from a Pile of Shoes: Chronic Illness, Kids, and Creation,” was published by Literary Mama, and you can find her interviews at Invisible Not Broken Podcast, Montana Public Radio, and Writing It Real. She is a professor of English at Western Washington University and a faculty member of The Red Badge Project, a non-profit organization serving veterans in Washington through the use of storytelling techniques.

Kathryn Trueblood’s newest novel, Take Daily As Needed, presents the challenges of parenting while ill with the desperado humor the subject deserves (University of New Mexico Press, 2019). She has been awarded the Goldenberg Prize for Fiction and the Red Hen Press Short Story Award. Her work is situated firmly in the medical humanities. Her previous novel, The Baby Lottery, dealt with the repercussions of infertility in a female friend group (a Book Sense Pick in 2007). Her story collection, The Sperm Donor’s Daughter, takes a look at assisted reproduction. Trueblood has offered workshops in therapeutic writing at The Examined Life Conference at the University of Iowa, the Hugo House in Seattle, and the Lighthouse Writers Conference in Denver. Her essay, “Writing from a Pile of Shoes: Chronic Illness, Kids, and Creation,” was published by Literary Mama, and you can find her interviews at Invisible Not Broken Podcast, Montana Public Radio, and Writing It Real. She is a professor of English at Western Washington University and a faculty member of The Red Badge Project, a non-profit organization serving veterans in Washington through the use of storytelling techniques.