Teadora and Papa Eye

She awoke slowly as she always did. The thin gray light filtered through the single small shutter into her hut. There was enough space for a pallet on the clay-dirt floor and a recess that held her day clothes. She glanced up over her head at the large orb of Papa Eye above her plaited sleeping mat. For as long as Teadora could remember—and she couldn’t remember very much at all—all-seeing Papa Eye was above, watching. Sometimes, as she prepared to sleep, she could feel the large single eyeball fixed unblinkingly upon her. Papa Eye was always awake, alert, always watching her. He lashed out at times, whenever she showed herself reluctant to go through her daily routines. His arms contracted, then flung out to slap her over and over—all over—until her clothes were shredded, her body stung, and she was covered in the thin mucus that kept him moist.

She couldn’t get away.

Sometimes in the morning, Teadora was sad. Sometimes she wondered at her unhappiness. She had a memory like a dream of others—people who showed clean white teeth as they laughed. She could almost get what they said, though she couldn’t really understand—it was just beyond her ability to comprehend. She knew that they talked and shared food passed around a large table shaped like the full moon—and they laughed.

She didn’t know why she felt these things. So Teadora washed under the seeing eye of Papa Eye, and sighed.

She was a tiny child and very thin. Her skin and hair—all of her—seemed bled of color. She was innocent of any knowledge of color. The woman, the only other human she ever saw, took away the basin of colorless water. The woman never spoke, and Teadora didn’t know if she even could speak. In all the time that Teadora could recall, the woman had brought her meals and other necessities, but the woman never met the girl’s gaze. She always seemed angry.

Sometimes Teadora felt alone in the world, but she took comfort seeing the woman each day, though the woman was cheerless and never smiled, and never said a single word to Teadora. Once in a long while, Teadora contrived to brush against the woman, hungry for contact, but the woman always pulled away, keeping to herself.

The child dressed herself under gaze of Papa Eye. Her outfits, skirt and top, were drearily gray. The sullen woman braided the girl’s long hair. Teadora sat on the floor of her hut and had her first meal of the day. The meal was always the same, grainy colorless material that had no taste, so gritty that Teadora’s teeth crunched. As always, she forced the material down because if she refused to eat, the woman wouldn’t come back for a long time—and Teadora couldn’t face all that time completely alone with Papa Eye.

The gray light filtered into the room. A humming noise always greeted her when she awakened, a sound that seemed to begin while she was waking and build in tempo and volume when she rose. The hum also seemed to increase to its loudest level after she had eaten. This was why Teadora liked to take her time about getting up and out of bed—in this at least, there was some variation. The woman took away the empty bowl in her usual resentful way. The humming was loud but smooth. She brought a cape for Teadora, for the girl’s twice-daily walk. The child didn’t remember a day when she didn’t do this.

The sky was gray and low, the water was of the same heaviness; it was like this every day. But Teadora found enjoyment in the ripples and flurries of wind on the water; in this there was variation. She sat on the silvery sand and looked out on the water. Her cape was large for her, engulfing. Papa Eye was painted on the back of her cape, ever vigilant. She watched the water, only half aware, feeling an ineffable melancholy. She thought, once again, of walking into the water, allowing the weight of the feathers on her cape and the weight of Papa Eye to sink her…

But she didn’t move. Surely Papa Eye could read her thoughts. She knew that Papa Eye could make her existence even more flat and gray than it was now. She looked up at the gray clouds. Teadora knew she was on an island, the island seeming to shrink smaller or swell larger in tandem with the hum that pervaded the place. The wavelets of the gray lake broke on the sand, the sand crunching and humming under her feet. She fastened her eyes on a piece of that heavy, leaden sky.

And the gray seemed to be thinner. She straightened. How could it be? Teadora stared at the thin spot, which slowly got lighter and whiter. The edges blurred and riffled, there was some texture, even, grainy and—something was moving up there!

Teadora wanted to flee back into her hut, but something inside her warned not to let Papa Eye see whatever this thing was. She was frightened, so scared she could barely move—or even breathe. There was a flutter of dark and light, a form, a shape. And then there was color!—a saffron-orange creature with a ruff around its neck, all fluffy, one round golden-orange eye peering at Teadora, then a second eye, as the thing turned its splendid head to study her, flying in a figure-eight over her. She thought with wonder, It’s a bird! Teadora accepted it without question. She was terrified that Papa Eye would see. She kept herself rigidly erect, though she wanted to throw herself down on the sand and cover her head with her cape. Her eyes were wet. It’s so beautiful! she thought, marveling at this visitation, still frightened.

The bird made a round, full-throated roar, opening its mouth very wide, the bestial noise drowning out the ever-present hum. It had teeth, two rows of sharp, triangular teeth, and curving claws at the tips of its wings. It’s a beast-bird! It smiled at her—or bared its teeth—as it regarded her. Then it redoubled the beating of its wings.

“No!” Teadora cried, her hands reaching upwards. But the glorious bird-beast flew back and forth and around the child, in larger and larger figures, its feathers stirred by the breeze. It rose higher and higher, then the orange seemed to melt into the gray clouds overhead. “No!” the child cried again, feeling the sting of grief behind her eyes. Tears rolled down her thin, wan cheeks and she sank to her knees, wondering dazedly if she had somehow imagined the wondrous colorful beast-bird with its mighty voice.

She put her hands into the all-too-familiar sand, scooping the grains and letting them run out between her fingers. Her head bowed, she watched her tears darken the sand, one drop, two drops, three. She knelt on the shore near the water. Papa Eye came down and hit her over and over until she was striped with scratches and welts and coated with slime. She lay curled on the sand, her outfit in tatters. Teadora pulled the cape over her head, her hair coated with mucilage, her body sticky.

After a long time, Teadora rose and slowly made her way to the waterline. She floated on her back, the tatters of her clothing drifting, her cloak weighing her down.

In the days after, the Eye followed her every move, remarked her every gesture. And the woman seemed now to hold closely to herself an air of excitement. It seemed as if the woman had a new avidity to her manner, as if there was some delectable fruit within her reach, to satisfy her desires. There was a spiteful gleam in the woman’s eye.

Teadora held herself still on her pallet at night, pretending to sleep. But each time she re-imagined the miraculous scene on the beach, her pulse beat harder. She was surprised Papa Eye could not see her heart throbbing within her breast. She would sigh and turn over, sneaking a quick look at the Eye above, the Eye open always. She’d think of all the gray days behind her, all the gray days before her, and force her excitement down, down into her soul, where no Eye could follow the thing that possessed her, something she had not known before she saw the bird.

Hope.

Each morning and evening, at the beach, she obediently wore her cape with Papa Eye guarding her back. But Teadora watched the sky, trying to find the spot where the gray had thinned to allow the beast-bird to burst into her world. Please, she thought. Please. Please. She didn’t know to whom—or to what—she was praying. But she did it anyway. Each day, Teadora rose, washed, dressed, ate, walked, ate, napped, walked, ate, undressed, washed, and then lay awake at night thinking—and hoping. She could see the fabulous creature, with its marvelous fur-feathers, half as large as the sky as it descended, circling, splendid against the stillness.

The moon waned and waxed full; the waters rose and fell during ebb and high tides. Teadora continued her walks, the spying Eye vigilant on the back of the feathered cape. One day she walked and walked, farther than ever along the gray sand, until she reached a tumble of basalt boulders she had never seen before. Too far, the cape seemed to say; the waves lapped against the rocks, almost inaudible as the hum grew louder. Teadora kept her eyes fixed upon the clouds. She climbed up onto a boulder and then another. This was not like other days. What will Papa Eye do? She glanced up, and there he was, Papa Eye, as always, watching, the black iris indistinguishable from the black pupil.

I have nothing to lose, Teadora decided. She clambered defiantly on the tall stones, fantastical and beautiful in shape, glancing up, until Papa Eye thrashed her. The thrashing stung, but Teadora climbed, the hum pitching higher as well, until she was at the top of the pile of boulders, and the hum became a shrill whine.

Then Teadora smelled a wonderful, delectable aroma, and her heartbeat quickened. She peered into the shadowed darkness between the three tallest stones, where there was a pool of water, and a glimpse of something in the water. Teadora caught her breath. There was a cup in the pool, a cup the size of a hand, made of burnished metal. She picked it up. The heady sweet aromas of flowers and fruits wafted upwards and over the girl. The cup smelled of nectar. The child breathed in the unbelievable sweetness and wondered—for the cup was empty. She was careful not to drop it as she began her descent from the boulders, using her other hand to lift her long skirt. She slowly made her way back down, Papa Eye humming uneasily in the gray sky. She handled the little cup and discovered that she could collapse it into a flat circle and pull it back open, though she could not see any kind of seam or fold on the silvery metal. Teadora clutched the cup, but it slipped away, as if alive, and fell into the water. Dreading its loss, she tried to scoop it back up, but the cup dragged back, as if it were taking in all the water surrounding the island.

And it was. Suddenly the cup was light and easily repossessed , but the water around the island was gone, the sand sloping down into mud. She stared where the seemingly endless water had been. She looked into the cup, which was half filled with silvery water.

As if in a dream, Teadora took a step forward. Then she took another. The hum surrounding her increased to the highest and loudest she’d ever heard it. She trembled. She reached up with her free hand and untied the dark ribbon bow around her throat and let the cape drop onto the sand, the Eye glaring at the featureless sky, at the girl, at the mudflats. Teadora went forth with the half-filled cup, her steps faster and faster where the seemingly endless gray water had been, trying to keep from spilling the silver liquid.

Above the shrill hum Teadora heard a wail; she turned and saw the woman where the water once met the land, the woman’s face an angry red orb, her mouth open, her harsh screeching somehow audible. The sounds urged her forward over the mudflats, toward sand dunes farther on, and whatever else lay ahead. She tripped through mud, saw pools of water with fishes. At the edges, reedy plants stood tall, their roots holding fast to the mud.

Papa Eye was right behind and above her, bobbing along the air currents and winds. Somehow, she kept the sweet water in her cup from sloshing out. She knew even a few drops might fill the shore. Her breath came in gasps. She still felt the fears that had always defined her days and night. Her feet were heavy with mud. Papa Eye thrashed at her again, leaving welts on her skin, humming. But Teadora kept moving. She hummed along. Humming along made the other hum go away. Humming along, she saw crabs, she saw mussels, she saw fish in pools. Marsh plants thrived. There were holes in the mud, and crabs scuttled into the holes as she neared them. Her feet made a sucking noise. Papa Eye was still with her, she saw as she turned to look over her shoulder, and she was exhausted now, but not as desperate as Papa Eye. Was he trying to herd her back to where she belonged? She kept walking through the reeds and grasses. Papa Eye bumped her hard, but it was like the impact of a balloon. Teadora did the impossible: she hit Papa Eye with a fist. Amazingly, he bounded back, untethered, floating away. In the enormous, shocked silence that fell, the water in the cup seemed impossibly deep, emerald deep, sapphire deep, streaming with mysteries. “I am not a thing that belongs, I am my own and these waters are mine!” Teadora shouted. But Papa Eye was gone on the wind, and whether he heard her or not no longer mattered.

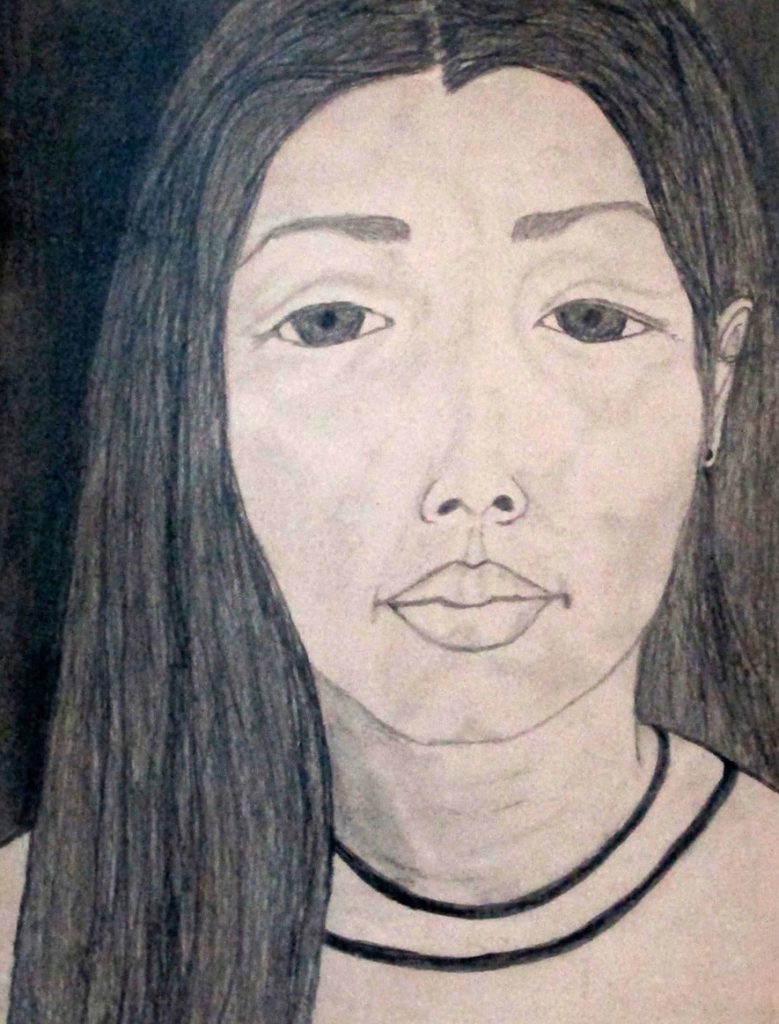

Angela Nishimoto was raised on the windward side of O‘ahu, has taught as a lecturer in botany and biology on the leeward side, and resides in Honolulu with her husband. Since the late 1990s, she has published more than forty pieces of prose and poetry. Her first book, Isabella’s Daughter, is a literary romance that was published by Pueo Press in Kāneʻohe.

Self-portrait by Angela Nishimoto

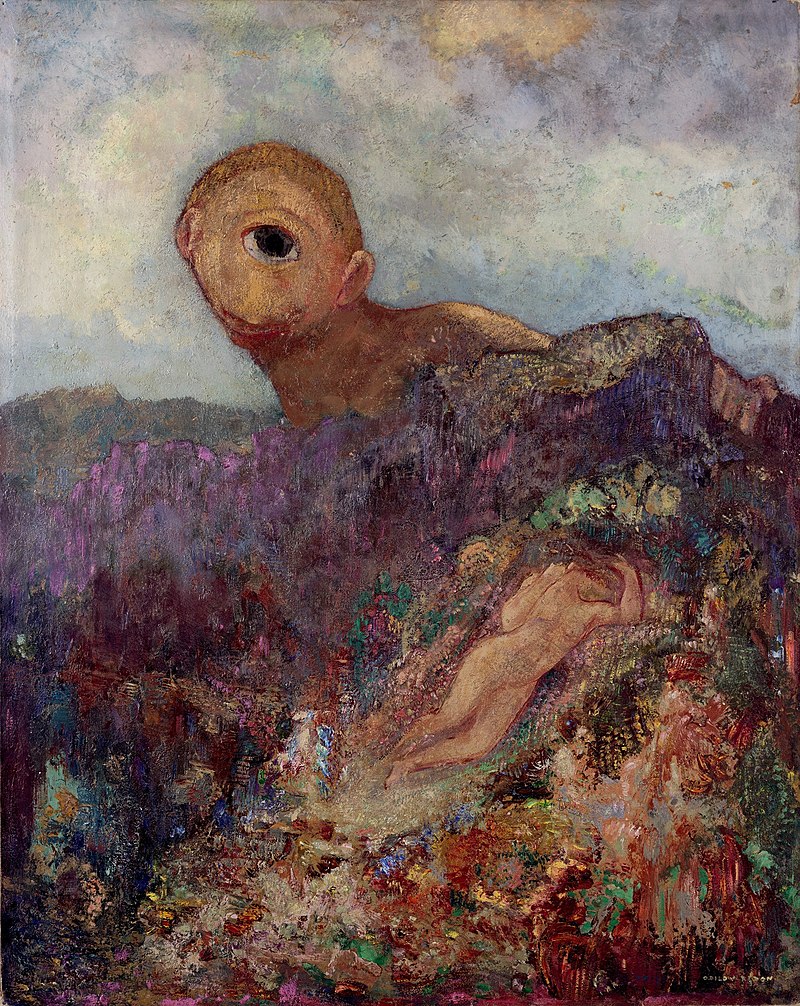

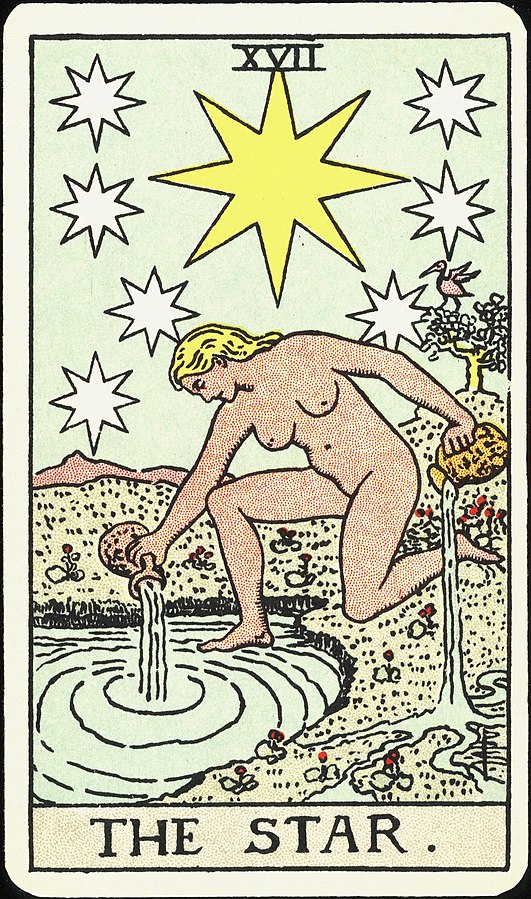

Public domain images from Wikimedia Commons (top to bottom): The Cyclops, Odilon Redon; Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, Hokusai; The Star, Waite-Smith Tarot Deck.