Olive Trees and a Hunter’s Moon

Haas Mroue was my friend, but seemed more like a brother to me. The last time I saw him was for one day in February 2007. He had been living half-time in Port Townsend, Washington, and half time in London, where his mother resided. I had been living for decades in Hawaiʻi, so there was always the distance, but we managed to navigate it. He called me one day that February to say he was flying out to see me the following day. He had booked a one-night stay in a Waikīkī hotel. That he would fly over five thousand miles round trip for a one-night stay was extraordinary, but that was Haas, extraordinary. I was thrilled. The next morning, I made a batch of gazpacho for him for the evening then drove to the airport to pick him up. We decided to go to the Kahala Hotel near Diamond Head. We sat all afternoon there at the outdoor bar area fronting the ocean. He was delighted to introduce me to mojitos while we talked story—about writing, his teaching at Berkeley in the Poets for the People series, about travel, food (he loved to cook) and Lebanon, the civil war (1975–1990) during which he had grown up. And, he talked again about his father’s death six months before he was born, all the things that haunted him and inspired his writing. He flew back home the following day. He would be going to London, then to Beirut on a year’s sabbatical and wanted to see me before leaving.

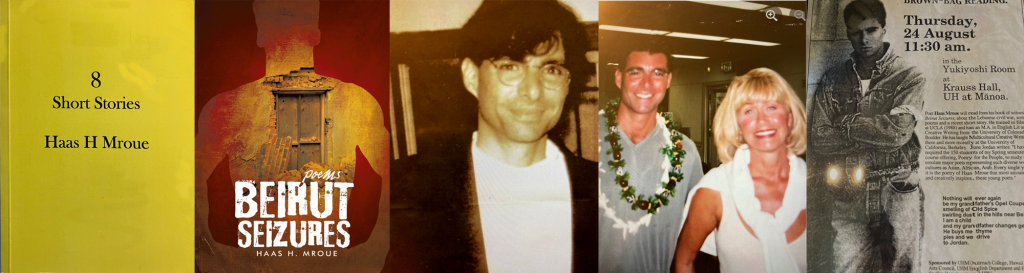

Though we didn’t know it then, it was fitting that our last hours together were spent at the Kahala Hotel as our first visit together had been there nearly fifteen years before. Haas had come to Honolulu to do a reading from his collection of poems, Beirut Seizures, and I had been in the audience that night. After his powerful reading of war poems, we had an easy and meaningful conversation. There was an immediate recognition of all we had in common being Lebanese: the language (he spoke Arabic, English, and French, as many in Lebanon do), and especially certain idiosyncratic Lebanese customs. We were both foodies who loved to entertain friends. Lebanese hospitality is legendary. Then there was our love of poetry, so we decided to meet at the Kahala Hotel for lunch the next day.

That was the beginning of a deep and abiding friendship that included writing letters, sharing poems and stories constantly and having long phone conversations about poetry and Lebanon, my family’s tragic history there and his experience of growing up during the Lebanese civil war. He returned to Hawaiʻi later to teach a class at the University of Hawaiʻi Mānoa on travel writing and to give another reading from his new book. Having traveled the world, he had more than twenty travel books to his credit in addition to collections of poems, short stories, and plays. He had studied the craft both at the Sorbonne in Paris and at UCLA. He was an incredibly kind and generous person, as when he arranged an invitation from UC Berkeley for me to do a reading from my book of poems and conduct a poetry session with his graduate class. His students openly displayed their warmest affection and respect for him. We had a fabulous time at Berkeley together.

I can say that after many visits, as a house guest he was exceptional. He would often bring me a box of Lebanese specialty items, including the exotic pomegranate syrup. He took over the kitchen to show me how to make Fattoush, a wonderful Lebanese salad using the specialty ingredients that he brought with him. And another time he insisted on making another fine dinner of Kibi and Lebanese rice pilaf along with a yogurt cucumber and mint salad for my brother who had flown in from California for a short visit. One summer, we spent long weekends at a friend’s house on the beach at Rocky Point, on O’ahu’s north shore. I would often find Haas out on the sprawling white beach around sunrise. He would be working out the plot progression of a new screenplay. Those quiet times on the beach, in the water, were marvelous.

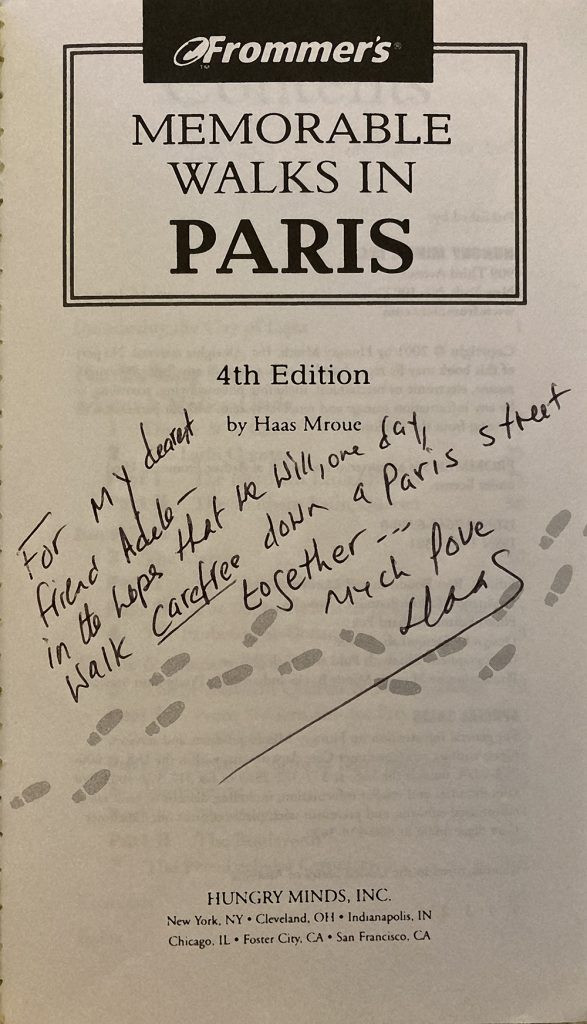

Later our time together would come to include my travel to San Diego to visit his friends and my family, to Marin County—a writer’s retreat that was really an excuse to tour wineries and have wonderful dinners together at the vineyard’s edge. Later, it included a trip to Paris, the South of France, and Monaco. Haas was writing an updated version of his fourth edition of Frommer’s Memorable Walks in Paris, and we did them all together. This included evaluating the dining experience in various restaurants. What a way for me to see Paris for the first time! We stayed in a hole-in-the-wall hotel near the Pont d’ l’Alma near where the golden flame for Princess Diana was erected, but we also enjoyed our complimentary rooms at the Plaza Athene, where we had sumptuous meals. Among many outings, we had lunch one day at the Closerie des Lilas, where Hemingway wrote most of The Sun Also Rises. Haas knew the City of Lights like the back of his hand.

Then we flew to Nice to visit his auntie in her villa in the hills overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. We drove the Cote d’Azur, had the best fish cassoulet and pear sorbet one night in San Tropez. We marveled at the midnight moon over the peninsula at St. Jean Cap Ferrat. After a day at the beach, La Plage Tahiti, we enjoyed a wonderful meal in the mountains of Ramatuelle, sitting near a grove of lit up olive trees that quivered in the wind and reminded us of how the olive branch is a symbol of peace. That had been a night of peace and friendship we both treasured. The meal ended with fresh figs and a Rose wine. But Haas always carried the weight of the war, his childhood trauma, with him wherever he went. You could feel it. In a way, we had that in common as my Christian family had suffered sectarian violence in Lebanon and eventually died there during the first world war, a transgenerational trauma, I have come to believe, that flows in the veins. Still, he had always urged me to visit Beirut. It’s good now, he would say, you have to go.

Eventually, we planned a trip to Lebanon together for the summer of 2006. Haas had said that after the end of the long war it was undergoing a massive renaissance, so many young people returning, the outdoor cafés were crowded and the energy in the city was electric. I bought my ticket, and we were ready to leave in days. But then the July war between Israel and Hezbollah broke out. Thirty-three days of carpet bombing destroyed everything as far as Jounieh, 20 kilometers north of Beirut. I had been emailing Haas’s cousin, Lena, during the bombing campaign that had nearly reached her village, Beit Meri, above Beirut. She said in one message to me, you must have been born under a lucky star not to be here now. I was heartbroken that my first trip to Beirut where my father had been born, where my mother’s people had lived, was cancelled. And, I was heartbroken for Lebanon again suffering more destruction. Haas was devastated to know that Lebanon was under fire again.

He died suddenly in Beirut while on sabbatical the following year. It was during the month of October when a huge Hunter’s moon was glowing orange in the night sky, a signal to prepare for winter. And, it was not so long after our last visit in Hawaiʻi. He had been fixing dinner for friends in his mother’s flat in Hamra and was having a glass of wine on his balcony when his heart gave out. He was forty-one years old. I have always felt that he was a later casualty of the civil war. As Etel Adnan says of his poems, “the old order and the new have created a brotherhood of disasters.” The loss was immense. I flew to Port Townsend for a memorial that was being held for him there. The following day, I walked out on the dock in front of his home with glorious views of the Straits of San Juan de Fuca, and I remembered how often he had said he loved this landscape, the quiet, peaceful place that it was for him finally.

In the spring of 2009, I made my first visit to Lebanon with my daughter. We had been invited to show our work together at the Sharjah, UAE Biennial. Only a three-hour plane ride away, we organized a side trip to Beirut. The destruction of the 2006 war was visible everywhere as was the rebuilding Lebanon has repeatedly undertaken. The resilience of these people is remarkable. Nothing breaks their spirit. The energy of the city was still electric, vibrant, just as Haas had said. I was thrilled to finally walk the streets where my parents and grandparents had started out, but I was sad not to be discovering all of it with Haas. We found our ancestral village in the Chouf mountains, which Haas had visited and written to me about, and we visited Byblos, the ancient harbor full of fishing boats rocking back and forth in the March wind. Finally, we travelled south to Saida (Sidon) to visit his Aunt Ruby and Uncle Farid. It was a pilgrimage in so many ways. We had a long visit together by the fireplace in their study, sharing memories of Haseeb. (Because he traveled so much, Haas had legally changed his name, as it caused constant racial profiling at airports.) Later that afternoon Farid drove us to a cemetery overlooking the sea, the entrance guarded by a soldier in fatigues with an automatic weapon. Haas had been buried there near a grove of olive trees in the same grave as his father. I got to say my final goodbye.

Tragically, Gaza and Lebanon are now suffering great destruction and carnage—again. Haas was a Lebanese Jewish-Muslim. He hated war, and wrote in one of his poems, “Only the dead truly converse from Gaza to Auschwitz.” He hated the division that causes war, as illustrated by his use of East and West in “Civil War,” one of eight short stories published by his family in 2009. The dividing line between East and West Beirut was called the Green Line because the war lasted for so many years that trees and shrubs grew up in between bomb-shattered concrete. East Beirut was Christian; West Beirut was Muslim. Crossing the Green Line was deadly.

You sleep until evening by nightfall the rockets from the Green Line are too strong to ignore. The power is out. Your mother sits in the living room by candlelight knitting a sweater, you wonder if it is for you. She hears you getting up, going to the bathroom, and she goes to the kitchen to get your coffee. You sit facing her in the dark living room and listen to the rockets. You sip your coffee quickly. She smiles at you. She wants you to talk to her. You feel restless. You want to be outside, on the streets. You want to hold your A.K.-47. You want to feel the wind in your hair. She doesn't even look up when you go to your bedroom and walk out carrying your machine gun. "May God be with you," she says under her breath as you walk out the front door.

…

It starts to rain and the wind makes the rain fly. You look towards the East and wonder what is East and what is West. And with the wind in your hair and the rain in your eyes you pray for Claude and Mona and your father and the corpse behind the jeep and the cat that Bjorg killed. You pray for your country, for your city divided in two.

You are sitting on the terrace of the St. George Hotel Bar but you are falling.

Beirut is falling.

Everyone is falling.

Haas would be heartbroken now at the unspeakable loss of life everywhere in the Levant. He thought of himself as a citizen of the world. The epigraph for Beirut Seizures reads “My feet/recognize/no border/no rule/no code/no lord/for this/is the wanderer’s/heart— (Francisco Alarcon).” The last time we were together that day in February he said he didn’t want to write about war anymore. He said he wanted to go out to sea for the day with the fishermen of Byblos and write about simple things like fixing fresh catch for dinner. In “Beirut Survivors Anonymous,” the poem ends with the lines “We are young / and need to shield our eyes.”

When I returned to Lebanon the following year in 2010, after first stopping in London to see Haas’s Auntie Zein and his mother, Najwa, I walked along the Corniche alone, the promenade fronting the Mediterranean Sea that Haas loved so much. I recalled then Paris and the words he inscribed in my copy of Frommer’s Memorable Walks in Paris, which he had given me long before we traveled there together: “For my dearest friend Adele—in the hope that we will, one day, walk carefree down a Paris Street together. Much love—” I am ever grateful that we got to do that. And, I know that Haas would now be longing for peace and desperately wishing for a “carefree” walk down any street for all the peoples of the Levant.

Adele Ne Jame, first-generation Lebanese American, serves as Professor Emeritus at Hawaiʻi Pacific University. Previously, she served as the Poet-in-Residence at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her books of poems include Field Work and The South Wind. Her manuscript in progress is “First Night at the Beirut Commodore.” Among her honors are a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in Poetry, Elliot Cades Award for Literature, a Pablo Neruda poetry prize, and a Robinson Jeffers Poetry Prize. She is also an Atlanta Review International Poetry Prize winner and served as a Mikhail Series Lecturer at the University of Toledo in 2022. Her poems were exhibited as broadsides along with her daughter’s paintings in the Sharjah, United Arab Emirates International Biennial, at the Arab American National Museum, Dearborn, Michigan and at the Donkey Mill Arts Center, Kona, Hawaiʻi, 2024.