Expansion of the Pacific Remote Islands and Papahānaumokuākea marine national monuments did not cause economic harm to the Hawaiʻi-based longline tuna fishing fleet, according to a study led by an economics professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

The results of the study, supported by the Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, represent the world’s first economic analysis of a large-scale marine protected area (MPA) post designation. The study’s co-authors, including John Lynham in the College of Social Sciences, analyzed observer records of individual fishing events, logbook summary reports and detailed satellite data on vessel movements.

“By analyzing independently collected data, we found that catch per unit effort has increased for the Hawaiʻi-based longline industry following each expansion,” said Lynham. “The bottom line is that these monuments are not causing substantial economic losses to the fishery.”

Study results are clear

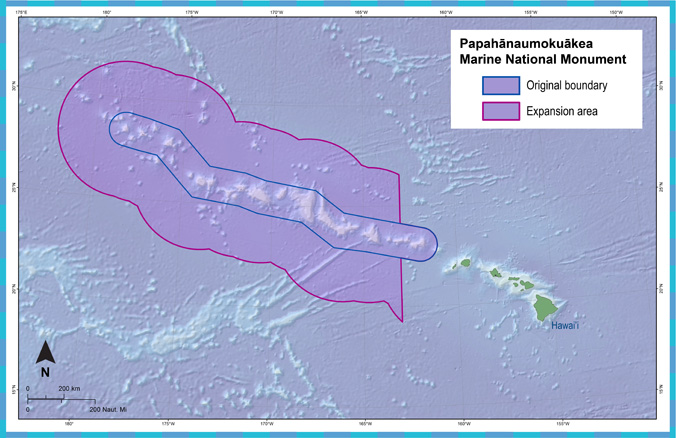

In 2014 and 2016, President Barack Obama significantly expanded the monuments, collectively protecting a little more than one million square miles (2.78 million square kilometers) of healthy coral reefs, undocumented deep-sea creatures and large predatory species such as sharks, tuna and marine mammals. This built upon actions taken by President George W. Bush, who designated both the Pacific Remote Islands and Papahānaumokuākea marine national monuments in 2006 and 2009, respectively.

“The effect of an MPA on a fishery is often difficult to assess because of the many factors that affect catch such as ocean conditions, prices and changing regulations,” said Lynham. “A strength of this study is that by comparing the longline tuna fishery to two other fisheries unaffected by the monument designation, we’ve controlled for factors that could be biasing the results.”

“Our conclusion from this is clear: Papahānaumokuākea and the Pacific Remote Islands marine national monuments have not hurt the fishing industry overall,” Lynham continued. “This is not too surprising when you consider that, in 2015, when Papahānaumokuākea was open to fishing, 97 percent of fishing was taking place outside the monument in waters that are still open to fishing today.”

Prior to the expansion of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, representatives of the longline fishing industry in Hawaiʻi argued that the expansion would result in direct losses as high as $10 million annually, and that total indirect losses to the fishing-dependent economy could reach $30 million. The new analysis shows that, after the expansions, the Hawaiʻi-based longline industry has been catching more fish, while the distance that the fleet travels has remained unchanged.

Moreover, the total catch and total revenues in the fishery have increased since the expansions began. Specifically, the average revenue from 2014 to 2017 was 13.7 percent higher than from 2010 to 2013.

The paper, titled “Impact of two of the world’s largest protected areas on longline fishery catch rates,” was published in Nature Communications.