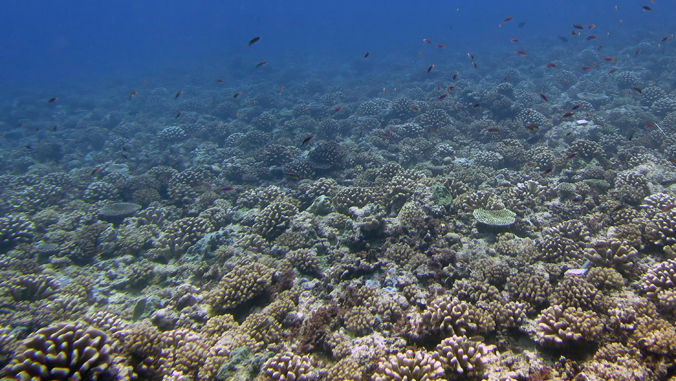

New research has uncovered just how chemically diverse coral reefs really are. Thousands of different substances released by tropical corals and seaweeds aren’t just floating away—they serve as food for tiny ocean microbes that break them down and recycle them.

The study, published recently in Environmental Microbiology by an international team led by University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) scientists, provides crucial insights into the intricate relationships between coral reefs, marine microorganisms and the carbon cycle.

In the future, the team aims to continue discovering how chemical features can inform coral reef management and be used to advance coral restoration success.

Coral reefs are busy, efficient ecosystems—especially in nutrient-poor waters where nothing goes to waste. Microbes play a starring role, breaking down and recycling what other organisms leave behind.

“We’ve known that some of the substances exuded on coral reefs, termed exometabolites, are available for microbial metabolism,” said Craig Nelson, professor in the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. “However, in this study, we discovered that the number and variety of exometabolites that microbes find useful is much higher than previously considered, and includes hundreds of compounds spanning most of the broad chemical classifications.”

“We were especially surprised to discover that exometabolites belonging to chemical families traditionally thought to be harder for microbes to break down, such as benzene rings, terpenoids, and steroids, were among those that are able to be utilized,” said Zachary Quinlan, lead author, postdoctoral researcher at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology in SOEST, and former graduate student at SIO. “Our results paint a highly dynamic picture of ecosystem production of bioavailable substrates and their effects on microbial metabolism relevant to carbon cycling in coastal marine environments.”

Carbon cycle and reef resilience

The ocean holds an enormous reservoir of dissolved organic material—including what’s released by coral reefs—and it stores as much carbon as the entire atmosphere. How microbes process this material plays a big role in the global carbon cycle.

When there is a shift in the types of organisms living on a reef, that is stony corals versus fleshy seaweeds, the chemistry of the seawater also changes. In addition to their detailed study of what chemicals are being released on the reef, the research team also conducted experiments to determine whether microbes preferred to use substances from stony corals or seaweed.

“We observed that coral and algae can selectively facilitate the growth of specific microbial communities by exuding distinct chemicals that can be used by specific types of microbes,” said Linda Wegley Kelly, senior author on the study and associate researcher at SIO. “Our results highlight how shifting from coral-dominated to algae-dominated reefs can alter reef ecosystem function and impact resilience of the system, potentially making it more susceptible to disease or bleaching.”