On the evening of October 30, 2004, the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa experienced a disaster triggered by 10 inches of torrential rain that caused the Mānoa Stream to overflow and flood the campus. Hamilton Library and the Biomedical Sciences Building (BioMed) were the hardest hit, and 30 other buildings were also impacted, causing an estimated $80 million damage.

“The 2004 Mānoa flood was one of the most challenging moments in our university’s history, but the resilience of our UH ʻohana was extraordinary,” UH President David Lassner, who led UH Information Technology Services at the time. “Twenty years later, we stand stronger, united by the lessons learned and the community spirit that emerged from that devastating night.”

Hundreds of volunteers showed up the morning after the flood to save what they could and begin the monumental task of cleaning up the devastation left behind. Private citizens almost immediately started sending in donations, and elected officials, led by Hawaiʻi‘s congressional delegation, secured tens of millions of dollars in funding to repair and renovate.

Related: Biomed’s recovery, resilience after the 2004 Mānoa flood, October 2024

“This is not something that was fixed in a week, or in three months, or in even two or three years,” said UH President Emeritus McClain at a 10th anniversary event. “This is something that took a long time to fix.”

Hamilton Library

Nearly half of the flood’s damage occurred at Hamilton Library, where the basement was the center of destruction. The basement housed a vast collection of government documents, maps, and rare historical materials valued at $34 million. Up to 8 feet of muddy water submerged the entire area, destroying irreplaceable collections.

We stood on a couch and escaped by breaking through a window, forming a human chain.

—Andrew Wertheimer

“We thought, ‘A few inches—how bad can it be?’ But when we arrived, it was shocking. Cars were swept away, and bookshelves collapsed,” recalled Gwen Sinclair, head of Government Documents and Maps.

Andrew Wertheimer, Library & Information Sciences associate professor, was teaching a weekend class when floodwaters breached the basement. “We stood on a couch and escaped by breaking through a window, forming a human chain. It was kind of a miracle that we were all able to survive.”

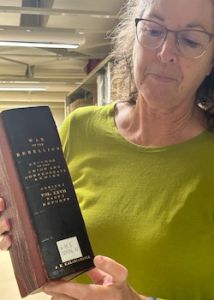

Teams of volunteers worked around the clock to save what they could, drying documents and books on clotheslines set up throughout the library. While some materials were salvaged, many rare items were lost forever, including most of Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole‘s Civil War books.

“It was like a war zone,” said Patricia Polansky, Russian bibliographer. “I still weep thinking about the treasures we lost. Among them was the New Testament in the Yakut language I brought back from the Soviet Union.”

Coordinating cleanup and restoration

Hawaiʻi CC Chancellor Susan Kazama was head librarian at Kapiʻolani CC at the time. She previously spent 12 years working at Hamilton Library and returned to assist then-University Librarian Diane Perushek, playing a key role in coordinating the cleanup and restoration efforts.

“My role included everything from pulling out computers and documents from the mud, securing frozen storage for documents, restoring air circulation, relocating staff, and helping recover personal items such as irreplaceable family photos and even prescription glasses in the first two weeks,“ Kazama said.

Over the next few years, around 60 to 80% of the lost maps and documents were replaced, thanks to donations and acquisitions from libraries worldwide. By 2010, after extensive repairs and renovations, Hamilton Library fully reopened. The basement, housing the Government Documents and Maps collections, as well as cataloging, serials, and acquisitions departments, was also restructured with new protective measures.

Upgrades and lessons learned

The 2004 flood prompted significant facilities upgrades at Hamilton Library to prevent future disasters.

“There was a moat around the building that allowed water to flood through broken windows and doors,” said Steve Pickering, the library’s building manager.

In the reconstruction, the moat was sealed, large drains were installed to divert water, and concrete walls replaced plasterboard in vulnerable areas. The chiller plant and electrical room were also relocated.

“If the same weather event occurred again, the library wouldn’t flood,” Pickering said. “Water now flows around the building, not through it.”

Kazuko Hioki, the library’s preservation librarian since 2017, highlighted disaster preparedness improvements since the 2004 flood, including a large freezer for water-damaged materials and a preservation specialist role for preventive measures.

The preservation department, now nationally recognized for flood recovery expertise, often consults on similar disasters. Hamilton Library continues to grow its collections through donations and digitizes materials with its state-of-the-art digital lab.

“It was an unforgettable experience, and not something I like to dwell on,” added Sinclair. “Yet, 20 years later, I will always remember the hundreds of volunteers who responded in those first few weeks of the flood, a testament to the enduring spirit of human resilience.”

Flood leads to new IT Center

The Information Technology Center that opened in February 2014 on the UH Mānoa campus was in large part a response to the flood. Before the center was built, the IT systems were spread across different buildings on the UH Mānoa campus, usually on the bottom floors or the basements. During the flood, water got within yards of the main data center and threatened all UH institutional information and communication services as well as Internet connectivity for UH and the State of Hawaiʻi.

“The flood of 2004 demonstrated the high level of enterprise risk faced by housing IT resources on the ground floor of a 50-year-old classroom building,” said Lassner when the IT Center was opened. The main data center is now located on the second floor of the IT Center.

Read more about BioMed Building’s flood damages and recovery.