Vibhu Vivek, a pioneer in the field of life sciences and engineering, leveraged the academic and research foundations he established at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa College of Engineering to launch a pair of companies in the life sciences industry.

His unexpected journey started when he was a graduate student from 1999–2000 in the Department of Electrical Engineering and he made a mistake working with ceramics in the Physical Electronics Lab. Vivek accidentally cracked a wafer, a thin slice of piezo ceramic material that generates ultrasonic waves when excited with radio frequency energy, and discovered that the crack propagated in a way that it segmented the electrodes resulting in a unique ultrasonic signature. This distinct pattern or characteristics of ultrasonic energy possessed very high levels of lateral ultrasonic waves when driven by high frequency radio frequency waves. When this ultrasonic energy was transmitted into fluids, it resulted in highly localized microscale mixing and fluid motion. This “mistake” became the topic of his thesis and much more.

“It’s all about serendipitous discoveries in the lab, simply by staying attentive, open-minded, and acknowledging the vastness of the unknown, but still continuing to progress forward fueled by your beliefs in yourself and innovate in every step along the way,” Vivek said. “But it is important to recognize that innovations happen in small ways.”

Vivek became the president and chief technology officer for Microsonic Systems, Inc. and used what he discovered at UH to create an award-winning product called the HENDRIX SM100 Ultrasonic Fluid Processor, which utilized high-frequency ultrasonic waves to mix, solubilize and homogenize fluids with high precision for various industrial and research applications. The fluids could be biological (blood, plasma and cell suspensions), pharmaceutical (drug formulations and vaccine suspensions), industrial (oils, lubricants and solvents) and more.

His company sold systems to top-tier pharmaceutical companies, such as Merck, Pfizer, Novartis and Astrazeneca. This product helped with the discovery of new drug formulations and the product was named a winner of the 48th Annual R&D 100 Awards (Oscars of innovation) in 2010. Vivek also received multiple grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health and NASA to further expand this technology.

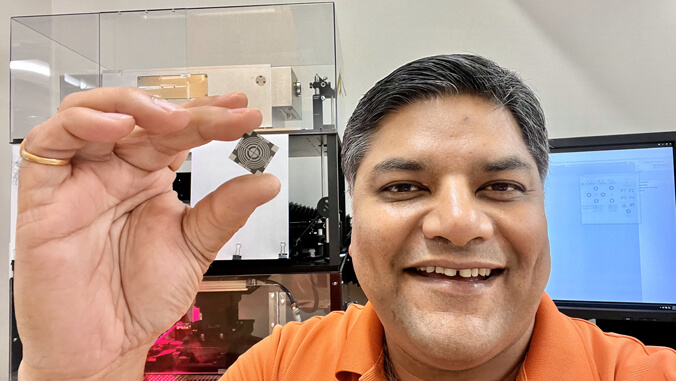

In 2017, Vivek founded and became the chief technology officer for Cellsonics Inc., a life sciences technology company that has re-engineered single cell sample preparation in the field of genomics, cancer research and personalized medicine by dissociating live single cells from tissue samples using the ultrasound technology invented at UH.

Forming the foundations at UH

A native of India, Vivek graduated with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Jamia Millia Islamia, and was pursuing his master’s degree in electrical engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi before transferring to UH Mānoa.

“The Department of Electrical Engineering was well known for the work they did, especially in the Physical Electronics Lab during the early days of the cold war where a lot of semiconductor technology was developed funded by the Department of Defense,” Vivek said. “There was always a potential for me to innovate and create new ideas in the department.”

He graduated in 2000 with his master’s in electrical engineering and was a research associate in the Physical Electronics Lab, before leaving for the U.S. continent to pursue work opportunities. Vivek credits UH Mānoa with helping him get his start in physical electronics, which includes nanotechnology, Micro Electro Mechanical Systems, semiconductors and more.

“My undergrad expertise was in robotics and electrical power engineering dealing with large machines. Going from really large, high voltage and big machines to working on small semiconductor electronics enabled me to think differently when compared to a conventional electronics engineer,” Vivek said.

Because of that experience at UH Mānoa, he said, “That was foundational in pretty much everything I do today. In order for somebody to continuously innovate and be successful, one should not only have deep knowledge in one domain but should have the ability to apply it on other domains.”

Vivek explained that despite lacking formal education in life sciences, he primarily works in that field. Originally trained as an electrical engineer, he found himself immersed in molecular biology and biochemical processes. For current and future UH engineering students, Vivek’s advice is to always try to go out of your comfort zone and seek the unknown. He believes that stepping into unfamiliar territory creates opportunities for fusion and ultimately fosters innovation.

“Typically, individuals with an engineering background tend to pursue careers in engineering. However, by venturing beyond one’s comfort zone and embracing new domains such as biology or economics, one can not only utilize their engineering skills but also cultivate new ones,” Vivek said.