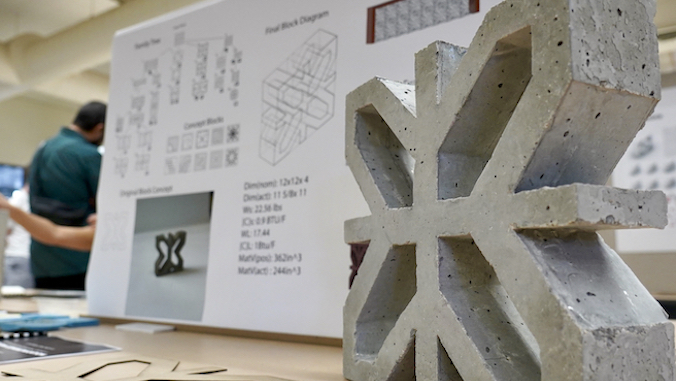

Sixty-five budding architects at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa showcased their design skills at the School of Architecture’s annual freshman breeze block design open house on February 22. Breeze blocks are commonly seen around Hawaiʻi neighborhoods and buildings where concrete blocks are integrated for air flow and design elements.

“Now in its 10th year, this event has become a hallmark for our first-year architecture students, which introduces them to a hands-on, small-scale project experience focusing on a single building element and material,” said Associate Professor Lance Walters who leads the course, Arch 102: Design Fundamentals Studio II.

The open house displayed each student’s intricate work of a full-sized concrete breeze block that they created through various iterations over the course of five weeks. Accompanying these pieces were small-scale model blocks and a detailed chronicle of their design journey presented in a book.

Key takeaways for success

Students begin their projects by studying the presence and significance of breeze blocks throughout the island, exploring how these durable and ventilated building materials have not only thrived in the tropical climate but also become integral to the architectural identity in Hawaiʻi. Students then translated their research into unique designs to create their own breeze blocks.

Student Quincee Natividad took his inspiration from the desert landscape and architecture depicted in the science fiction film Dune.

“‘Dune Block’ is a triangular breezeblock model where the surface is extruded on multiple sides, inside out. The structure is solid, but the airflow is not so good,” he explained, saying the constructive critique he received in the creative process helped him refine his final design.

Isabella Morillo’s design called “Squidly” is inspired by squids and the organic lines of the creature’s head, with lots of air space and flow she found reminiscent of the architecture in Greece.

“This was a great foundational course where I got to learn how to pour my own concrete, create models using computer applications and woodworking,” Morilo said. “Overall, the biggest takeaway was not to force an idea no matter how much you love it.” Like Natividad, she emphasized the importance of getting feedback to continually improve the design.

Faculty, upperclassmen and graduate students and local professional architects were invited to meet the student designers and provide their feedback, including those who attended the school’s annual career fair that day. Renowned landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom from Thailand, who delivered a public lecture that evening, also provided her expert global insights into the designs.

Building blocks for future projects

Related UH News story: Giant architecture inflatables pop up at UH MānoaSubsequent projects in Arch 102 will build upon this foundation, incorporating project sites and culminating in a large-scale spatial design and build endeavor, such as the giant pneumatic structures that have been prominently displayed on the school’s lawn.

“Students not only gain insights into design principles and material usage but also hone their skills in design communication,” added Walters. “This emphasis underscores the importance of presenting and articulating their work graphically—a crucial aspect of architectural practice.”

Along with Walters, co-teachers My Tran, Tyler Francisco and Jay Moorman, who are also graduates of the school, provide their mentorship to the students throughout the year.