Climate change-induced ocean warming has reshaped reef ecosystems as coral bleaching events continue to lead to mass coral die-offs globally. A study led by University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa student researchers revealed that exposing rice coral larvae to warmer temperatures did not improve survival once the coral developed into juveniles and were exposed to heat stress.

Coral restoration efforts in Hawaiʻi are vast and include selectively breeding more resilient coral, active management of vulnerable areas and outplanting coral reared in a lab.

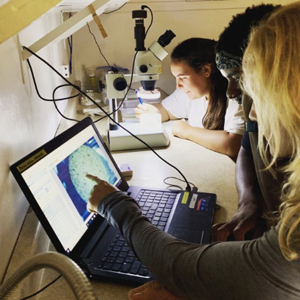

Shayle Matsuda and Ariana Huffmyer, marine biology graduate students in the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), were on a mission to optimize efforts to restore corals. While at the Inclusive Science Communication Symposium, Matsuda met Gyasi Alexander, an undergraduate student at the University of Rhode Island, and invited him to participate in a summer internship at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in SOEST.

Exposing larvae to different temperatures

The team’s approach was to start with gametes collected during mass spawning events and rear them to the larval stage, with the long term goal of planting more coral on the reef.

“Although this process can provide more genetic diversity to the reef than fragmentation practices alone, it takes considerable time, effort and capital, and the downstream survival of the corals may be impacted by ocean warming events,” said Matsuda who is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Shedd Aquarium. “With this study, we wanted to test whether exposing larvae to different temperatures would both increase larval survival and settlement, and importantly, if exposure to elevated temperatures as larvae would lead to increased thermal tolerance, that is, higher survival, at the juvenile stage.”

“However, we do not have a good understanding of the degree, time, and profile of stress required to produce positive carry over effects and, if the effects are produced, how long they last,” added Huffmyer, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Rhode Island.

In their experiments, the researchers, including HIMB coral ecologist Josh Hancock, found that elevating temperature to simulate future ocean warming did not improve larval survival and did not improve survival after larval settlement. Instead, their results suggest that rearing rice coral at ambient temperatures maximizes early life stage survival.

“As climate change intensifies, it is critical that we focus our restoration and conservation strategies on those that will have the greatest positive impact,” said Huffmyer. “Since we found that thermal conditioning did not provide positive benefits for thermal tolerance in recruits in this species, we suggest that our time and resources are best spent pursuing other avenues of thermal conditioning and further testing thermal conditioning scenarios that may produce positive impacts.”

This effort is an example of UH Mānoa’s goal of Excellence in Research: Advancing the Research and Creative Work Enterprise (PDF) and Enhancing Student Success (PDF), two of four goals identified in the 2015–25 Strategic Plan (PDF), updated in December 2020.

For more information, see SOEST’s website.

–By Marcie Grabowski