Witnessing a widespread coral bleaching event during the summer of 2015 sparked University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa student Mariko Quinn’s determination to conserve Hawaiʻi’s reefs. Growing up on the edge of the water of Kāneʻohe Bay, Oʻahu, Quinn spent many days exploring, swimming and snorkeling with family.

“Being in the water made me very passionate about the oceans and the health of the marine ecosystem from a very young age,” said Quinn, an undergraduate student in the Global Environmental Sciences (GES) program. “Seeing the coral bleaching event impact reefs both in Hawaiʻi and around the world prompted me to do my eighth grade science fair project observing how coral recovered after the bleaching.”

Connecting with UH marine scientists

At the state science fair, she connected with the Kulia Marine Science Club, an afterschool marine biology club for high school students at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST).

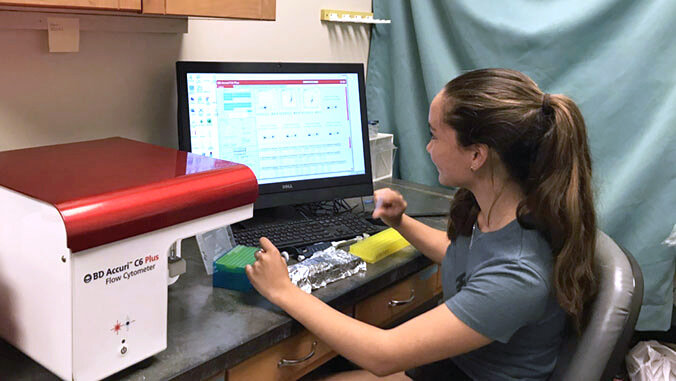

After her first year in the club, one of the instructors, Mike Henley became Quinn’s mentor to assist with her next science fair project on coral reef ecology. After a successful project, Quinn became an intern with Henley in the Smithsonian Institution’s Hagedorn Lab, based at HIMB.

“I have been consistently impressed with Mari’s dedication, performance, responsibility, motivation and reliability as a student and young researcher,” said Henley, who is also a postdoctoral researcher in the Hagedorn Lab.

Quinn continued working with the lab group on several different projects spanning from 2017 to this past summer as a student in SOEST’s GES program. Earlier in 2021, Quinn co-authored a study published in Nature Scientific Reports revealing that blue coral’s secret sunscreen may provide resilience to changing ocean conditions.

“I’ve been able to explore not just coral reef ecology but also coral restoration and reproduction,” Quinn said. “I’ve also learned a great deal about what goes into being a good researcher and how to design a successful large-scale experiment. One of the main things I’ve learned thus far is that failure is just part of the process. If an experiment doesn’t work the first or fifth time, it still moves the project and our scientific understanding forward.”

Personalizing her degree

Drawn to the holistic and relatively broad course curriculum, Quinn appreciated that the GES program covered a variety of topics with real-world applications, and that there is space for personalization and focus.

For her senior research thesis, Quinn plans to investigate the reproductive differences of the sea urchin, Tripneustes gratilla in locations around Oʻahu. This species of urchin is often known as an indicator species, as they are incredibly sensitive to changes in their environment, such as toxins or chemicals in the water.

“I also really enjoy how much support and community GES provides since it is one of the smaller programs on UH Mānoa campus,” Quinn said.

After graduation, she hopes to participate in the Knauss Fellowship Program in Washington, D.C. which allows students to connect policy and research in water-based ecosystems at a national level.

This work is an example of UH Mānoa’s goal of Enhancing Student Success (PDF), Building a Sustainable and Resilient Campus Environment: Within the Global Sustainability and Climate Resilience Movement (PDF) and Excellence in Research: Advancing the Research and Creative Work Enterprise (PDF), three of four goals identified in the 2015–25 Strategic Plan (PDF), updated in December 2020.

For more information, see SOEST’s website.

–By Marcie Grabowski