3,200 miles beneath Earth’s surface lies the inner core, a ball-shaped mass of mostly iron that is responsible for Earth’s magnetic field. According to NASA, this field acts like a protective shield around the planet, repelling and trapping charged particles from the Sun. In the 1950’s, researchers suggested the inner core was solid, in contrast to the liquid metal region surrounding it. New research led by Rhett Butler, a geophysicist at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), suggests that Earth’s “solid” inner core is, in fact, endowed with a range of liquid, soft and hard structures, which vary across the top 150 miles of the inner core.

Earthquake waves provide clues

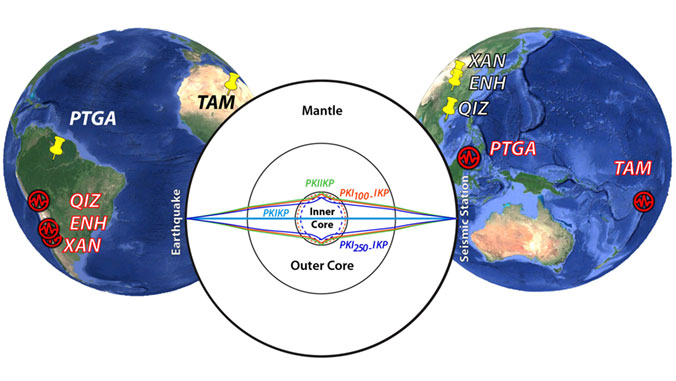

No human or machine has been to this region. The depth, pressure and temperature make inner Earth inaccessible. So Butler, a researcher at SOEST’s Hawaiʻi Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, and co-author Seiji Tsuboi, research scientist at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, relied on the only means available to probe the innermost Earth—earthquake waves.

“Illuminated by earthquakes in the crust and upper mantle, and observed by seismic observatories at Earth’s surface, seismology offers the only direct way to investigate the inner core and its processes,” said Butler.

As seismic waves move through various layers of Earth, their speed changes and they may reflect or refract depending on the minerals, temperature and density of that layer.

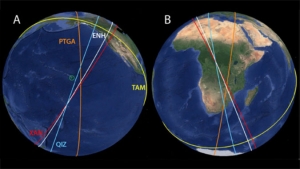

In order to infer features of the inner core, Butler and Tsuboi utilized data from seismometers directly opposite of the location where an earthquake was generated. Using Japan’s Earth Simulator supercomputer, they assessed five pairings to broadly cover the inner core region: Tonga–Algeria, Indonesia–Brazil and three between Chile–China.

Improved understanding

“In stark contrast to the homogeneous, soft-iron alloys considered in all Earth models of the inner core since the 1970s, our models suggest there are adjacent regions of hard, soft and liquid or mushy iron alloys in the top 150 miles of the inner core,” said Butler. “This puts new constraints upon the composition, thermal history and evolution of Earth.”

The study of the inner core and discovery of its heterogeneous structure provide important new information about dynamics at the boundary between the inner and outer core, which impact the generation of Earth’s magnetic field.

“Knowledge of this boundary condition from seismology may enable better, predictive models of the geomagnetic field which shields and protects life on our planet,” said Butler.

This work is an example of UH Mānoa’s goal of Excellence in Research: Advancing the Research and Creative Work Enterprise (PDF), one of four goals identified in the 2015–25 Strategic Plan (PDF), updated in December 2020.

For more information, see SOEST’s website.

–By Marcie Grabowski