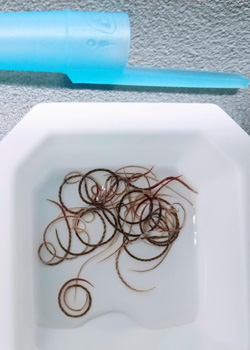

Different species of snails in Hawaiʻi host variable amounts of infectious rat lungworm, the nematode (roundworm) known scientifically as Angiostrongylus cantonensis, which causes rat lungworm disease. A recent study, led by a University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa zoology graduate student, revealed that environmental factors, such as rainfall, temperature and the extent of green vegetation, influence rat lungworm infection in snails.

In an effort to advance research and treatments for rat lungworm disease, researchers from UH Mānoa formed the Mānoa Angiostrongylus Research Group, led by Robert Cowie, a research professor in UH Mānoa’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST). Randi Rollins, who conducted the study, works in Cowie’s laboratory.

“The snail’s capacity to transmit rat lungworm depends on the environment and the host species, as human infection mainly occurs after ingestion of infected snails,” said Rollins.

In general, snails from rainy, cool, green sites have higher infection levels than snails from dry, hot sites with less green vegetation. However, rat lungworm prevalence does not increase at the same rate in conjunction with the environment in all snail species. Some species, such as Veronicella cubensis, large brown slugs commonly seen after rain, have very low infection levels in both hot and dry regions and wet and heavily vegetated areas. On the other hand, rat lungworm is more prevalent in giant African snails from wet, cool areas than in hot and dry regions.

“This interaction between host species and their environment highlights the importance of taking the ecology of species harboring agents causing zoonotic diseases into account,” said Rollins. “I strive to identify gaps in our knowledge that can create a safer Hawaiʻi and a more informed public.”

Collaboration at UH

The Mānoa Angiostrongylus Research Group includes scientists from the John A. Burns School of Medicine, the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources and SOEST’s Pacific Biosciences Research Center.

“The purpose of our group is to foster collaboration across Mānoa units and to highlight the significant rat lungworm disease research being conducted here at UH Mānoa,” said Cowie.

Every year in Hawaiʻi, rat lungworm disease is responsible for cases of debilitating illness, occasionally resulting in death.

In the past two years, the researchers, including experts in environmental ecology, parasitology, zoology and human and animal diseases, have published eight studies—sharing new discoveries and developing guidance for diagnosis and treatment of the disease. The team has compiled a comprehensive catalog of information on multiple species of Angiostrongylus, including other species that cause human and animal diseases; summarized rat lungworm disease and its treatment for veterinary professionals; reported canine cases of rat lungworm disease for the first time in Hawaiʻi; provided updated guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of rat lungworm disease; and is currently involved in a novel project of drug discovery to treat it.

This effort is an example of UH Mānoa’s goal of Excellence in Research: Advancing the Research and Creative Work Enterprise (PDF), one of four goals identified in the 2015–25 Strategic Plan (PDF), updated in December 2020.

For more information, see SOEST’s website.

–By Marcie Grabowski