Researchers from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa have confirmed, for the first time, water on the sunlit surface of the Moon. This discovery, which relied on NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), indicates that water may be distributed across the lunar surface, and not limited to cold, shadowed places. The findings were published in Nature Astronomy.

“Prior to the SOFIA observations, we knew there was some kind of hydration,” said Casey Honniball, the lead author who published the results from her graduate thesis work at UH Mānoa’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST). “But we didn’t know how much, if any, was actually water molecules—like we drink every day—or something more like drain cleaner.”

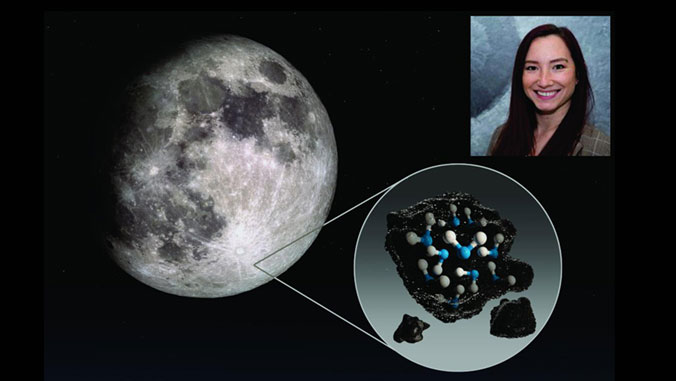

SOFIA detected water molecules (H2O) in Clavius Crater, one of the largest craters visible from Earth, located in the Moon’s southern hemisphere. Previous observations of the Moon’s surface detected some form of hydrogen, but were unable to distinguish between water and its close chemical relative, hydroxyl (OH). In analyzing these data, Honniball, Paul Lucey, a researcher at SOEST‘s Hawaiʻi Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, and their co-authors discovered water in concentrations of 100 to 412 parts per million—roughly equivalent to a 12-ounce bottle of water, trapped in a cubic meter of soil.

As a comparison, Sahara desert sand has 100 times the amount of water detected in lunar soil by SOFIA. Despite the small amounts, the discovery raises new questions about how water is created and how it persists on the harsh, airless lunar surface.

Building on years of research

SOFIA’s results build on years of previous research—using telescopes, satellites and astronauts—examining the presence of water on the Moon. Yet those missions were unable to definitively distinguish the form in which it was present—either H2O or OH.

SOFIA offered a new means of looking at the Moon. Flying at altitudes of up to 45,000 feet, this modified Boeing 747SP jetliner with a 106-inch diameter telescope reaches above 99% of the water vapor in Earth’s atmosphere to get a clearer view of the infrared universe. Using its faint object infrared camera, SOFIA was able to pick up the specific wavelength unique to water molecules, at 6.1 microns, and discovered a relatively surprising concentration in the sunny Clavius crater.

“Without a thick atmosphere, water on the sunlit lunar surface should just be lost to space,” said Honniball, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Yet somehow we’re seeing it. Something is generating the water, and something must be trapping it there.”

How is the water produced?

Several forces could be at play in the delivery or creation of this water. Micrometeorites raining down on the lunar surface, carrying small amounts of water, could deposit the water on the lunar surface upon impact. Another possibility is a two-step process whereby the Sun’s solar wind delivers hydrogen to the lunar surface and causes a chemical reaction with oxygen-bearing minerals in the soil to create hydroxyl. Meanwhile, energy from the bombardment of micrometeorites could be transforming that hydroxyl into water, trapped in tiny glass beads formed in the high heat from micrometeorite impacts.

SOFIA’s follow-up flights will look for water in additional sunlit locations and during different lunar phases to learn more about how the water is produced, stored and moves across the Moon. The data will add to the work of future Moon missions, such as NASA’s Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, to create the first water resource maps of the Moon for future human space exploration.

“Water is a valuable resource, for both scientific purposes and for use by our explorers,” said Jacob Bleacher, chief exploration scientist for NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate. “If we can use the resources at the Moon, then we can carry less water and more equipment to help enable new scientific discoveries.”

—By Marcie Grabowski