A book detailing Native Hawaiians’ experience with colonialism in the 19th century won a first place award by a leading international scholarly organization on indigenous issues.

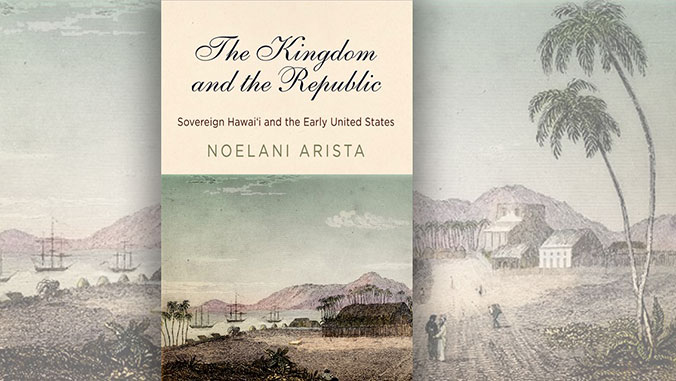

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Department of History Associate Professor Noelani Arista’s The Kingdom and the Republic: Sovereign Hawaiʻi and the Early United States was the winner of the Best 2019 First Book in Native American and Indigenous Studies Prize by the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA).

“I hope this award inspires Hawaiian students to become more interested in history, and to think that they can do what I am doing,” Arista said. “I think this award shows that Hawaiian history has a lot to offer scholars everywhere, not just those studying Hawaiʻi or indigenous history.”

Documenting historical records

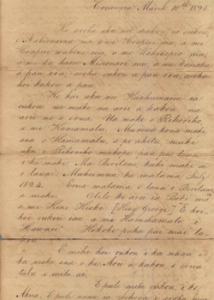

Arista combed through Hawaiian language documents to recount the history of the encounter between Hawaiian and non-native people in the 19th century. The book addresses political formation, indigenous law and encounters with missionaries and traders. Arista’s research involved travel to archives in Massachusetts and England.

“People find this astonishing, but an easy way to think about the archives needed to write Hawaiian history is to recall Hawaiʻi’s connections through trade, religion, family and labor,” Arista said. “Everywhere there was a connection to Hawaiʻi through these things—chances are there is an archive there.”

Research sources Arista utilized in Hawaiʻi were the Hawaiʻi State Archives and the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library. Arista said the largest textual collection in an indigenous language in North America and the Pacific is written and published in the Hawaiian language, and located in multiple U.S. archive sites.

“Most people assume that natives learn history from an ‘oral tradition,’ that we can only speak to our elders to learn, as if interviewing people constitutes the transfer of knowledge,” Arista said. “But in Hawaiʻi, we have the luxury of having some manaleo (native speakers), elders, who do not speak the language, and a huge textual archive.”

Arista said one of the most interesting things to focus on was correspondence between Hawaiians writing to one another, which is often sidelined in favor of accounts only in the English language.

“I also was surprised by the history I was able to relate when I put together pieces of the record, Hawaiian language sources written by Hawaiians to each other, sources which are often overlooked—together with the sources written in Hawaiian and English by non-native people,” Arista said. “This approach revealed the complexity of the past, rather than focusing on just a ‘perspective’ or different ‘accounts,’ but histories unfolding in worlds that were really just meeting for the first time.”

Reaction to the book

Shana Brown, associate professor and Department of History chair said, “Dr. Noelani Arista’s work is a transformative intervention in both Hawaiian and U.S. history. Her work challenges the idea of Hawaiʻi as passively impacted by U.S. law and institutions, instead offering a counternarrative of sophisticated and robust consensus-based political practice. She illuminates the historical legacy of the Hawaiian Kingdom as one of indigenous modernization, cultural flourishing and legal sophistication.”

The NAISA awards committee called Arista’s book “a rich history that draws extensively on previously unused Hawaiian language sources and the interpretation of cultural modes of political and legal speech. Arista offers a compelling new story of how Native Hawaiians exerted political influence and Indigenous law in the 19th century in response to colonial missions and markets.”

—By Marc Arakaki