Coral reefs may be eliminated worldwide by the year 2100. That’s according to new research by a University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa biogeographer and Department of Geography and Environment PhD student.

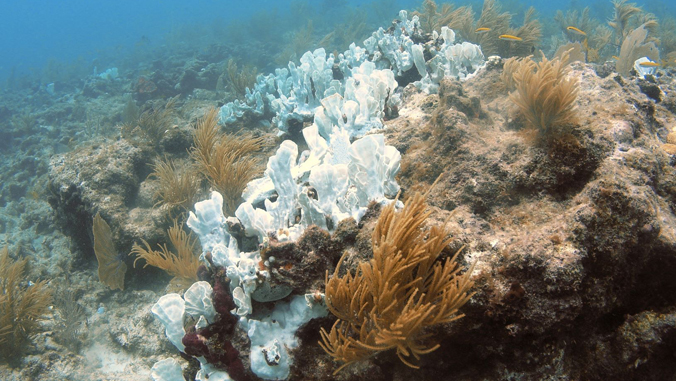

Along with pollution, rising ocean temperatures stress corals causing them to bleach. These corals are still alive, but run at a higher risk of dying. According to the new study, Renee Setter and her team analyzed sea surface temperature, wave energy, acidity, pollution and overfishing to determine that most coral reefs won’t be suitable habitats by 2045 and will worsen by 2100.

“I was saddened to find these results, but I was not entirely shocked as coral already face several stressors and have experienced great degradation in recent years,” Setter said.

Presenting her findings at the Ocean Sciences Meeting 2020 in San Diego, Calif. on February 17, Setter said that some scientists are attempting to grow healthy corals in a lab and transplanting them to dying reefs impacted by climate change and pollution. However, as sea surface temperatures continue to rise and acidity in the water increases, the corals have a “grim” future. Setter’s research shows that over the next 20 years, scientists predict 70 to 90 percent of coral reefs will be killed off. By 2100, few to zero suitable habitats will remain.

“Citizens can try to reduce the amount of stressors that coral face in order to prevent degradation of reefs,” Setter said. “This could be done by reducing carbon emissions and renewable energy sources as well as eliminating local pollution and reducing overfishing.”

Setter said that she now wants to see if corals may be more suited to live near the North and South Poles since areas near the equator are usually too warm.

“I am hoping to build upon this research by looking beyond current coral range to see if there may be any viable sites for restoration in higher latitudes. Since coral near the equators may face a great amount of thermal stress, we are interested to see if there are any sites in higher latitudes that may be more viable for restoration,” Setter said.

—By Marc Arakaki