Maunakea, Hawaiʻi’s tallest mountain, is one of the most revered places for many Native Hawaiians and astronomers. It’s also the only place in Hawaiʻi where you can find permafrost, a layer of ice and soil that is always frozen, commonly found in very cold regions of the world.

But the Maunakea permafrost, which may be over a thousand years old, is shrinking, possibly because of climate change. That’s according to research supported by the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo’s Office of Maunakea Management (OMKM), which is responsible for the stewardship of the mountain.

Scientists have been gathering data over a 10-year period to determine how the permafrost formed and persisted in an otherwise warm climate and is now on the decline.

“It is surprising to find permafrost in such a warm climate,” said Norbert Schörghofer, a planetary scientist and the lead researcher on the project.

The Maunakea permafrost was first discovered in 1969 by late UH researcher Alfred Woodcock inside the craters of two cinder cones on the summit—Puʻuwēkiu and Puʻuhaukea.

It was an unexpected discovery since temperatures are above freezing most of the time atop Maunakea. Researchers say that when the wind comes to a standstill, pools of cold air form in these craters at night. That cold air trapped between the rocks helps preserve patches of ice and frozen soil in the craters.

“The bottom of these craters experience the coldest temperatures ever measured in Hawaiʻi,” said Schörghofer, a planetary scientist. “These record temperatures are below zero Fahrenheit, far lower than on the summit itself.”

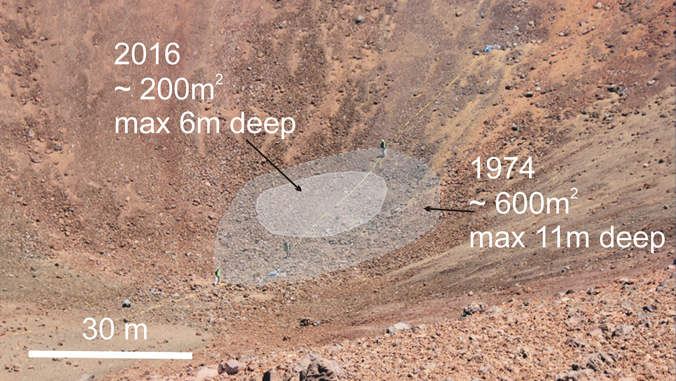

Researchers found that there is less permafrost now then when it was first discovered 50 years ago. Back in 1969, the ice at Puʻuwēkiu was 11 yards thick and 27 yards long, buried beneath one foot of boulders. Since then, Puʻuwēkiu has shrunk significantly and the remaining ice body is expected to disappear soon.

The other permafrost location in Puʻuhaukea is still at least 55 yards wide and about 11 yards thick.

“This is the last permafrost in Hawaiʻi,” said Schörghofer. “It should be studied before it disappears.”