An international team led by scientists from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa recently returned from a 34-day expedition to study deep-sea biodiversity and ecological processes in the western Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ). The expedition, aboard the UH-operated research vessel Kilo Moana, studied an area in the Pacific Ocean where numerous manganese nodule mining exploration claims are located.

“The diversity of life in these seafloor areas is really amazing,” said chief scientist Craig Smith, a professor of oceanography in the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. “We found at least 10 species of giant sea cucumbers, a huge squid worm never seen before in the Pacific Ocean and all kinds of sponges and other animals with really neat adaptations, such as sea cucumbers with long tails that allow them to sail along the seafloor.”

Can protected areas conserve biodiversity?

The data collected on this cruise will take many months to fully analyze, and is expected to substantially improve understanding of the biodiversity and ecology of the vast and poorly studied CCZ. The scientists will use these data to help assess the adequacy of conservation measures presently in place to protect deep-sea biodiversity in the face of seafloor mining. These data will be incorporated into a regional synthesis of the CCZ, to be used to make science-based recommendations to the International Seabed Authority and other stakeholders concerning environmental protection and management for deep-sea mining in the CCZ.

Said Jeff Drazen, project co-leader and UH oceanography professor, “This cruise was a wonderful opportunity to evaluate if three no-mining zones will be adequate protection for abyssal communities in the region before seafloor mining begins.”

Marine life and metals on the seafloor

More than one million square kilometers of the abyssal Pacific seafloor have been identified for possible seafloor nodule mining. Manganese nodules are a potential source of copper, nickel, cobalt, iron, manganese and rare earth elements—metals used in electrical systems and for electronics like rechargeable batteries and touch screens.

Deep-sea nodule mining is expected to result in the destruction of marine life and seabed habitats over large areas. This destruction has the potential to occur within sites directly mined as well as in adjoining areas impacted by sediment plumes created by mining activities.

The abyssal plains cover approximately 70 percent of the global seabed and are the biggest habitat on Earth’s surface. These seafloor habitats remain among the most poorly studied on the planet because they are remote and require specialist equipment to study. Yet, they may harbor an extraordinary diversity of organisms ranging from giant sea cucumbers to novel bacteria.

The research cruise, dubbed the DeepCCZ Expedition, was the first to study the wealth of organisms on seafloor plains and seamounts in areas currently designated as “no-mining areas” in the western CCZ. A major goal is to determine whether these protected areas are adequate to conserve the biodiversity in the region from the destructive activities of seafloor mining.

Exploring the diversity of life in the deep

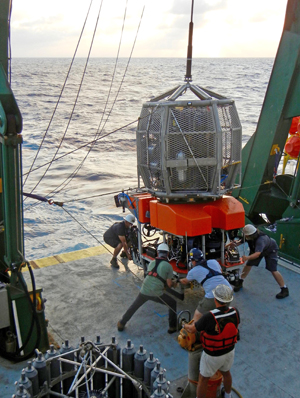

The expedition made 12 successful dives with UH‘s new remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Luʻukai, which used robotic arms and deep-sea cameras to photograph and collect animals, manganese nodules and sediments from greater than three miles deep. More than 100 species of large animals were collected or videotaped at the seafloor, many of which appear to be newly discovered species.

In addition to the ROV, the expedition used a broad suite of new deep-sea technologies to study the biodiversity and ecology of abyssal organisms ranging from bacteria to meter-long fish. State-of-the-art equipment designed to function at the enormous pressures of the abyssal ocean (more than 7,000 pounds per square inch) included an autonomous respirometer that descended to the seafloor to measure biological activity and food-web structure of deep-sea sediment communities, and baited stereo cameras that attracted and measured the mobile predators at the top of the deep-sea food chain.

DNA samples were also collected from the environment, and from individual animals, to test new approaches to assess biodiversity and ecological functions of microbes and animals living in sediments, on manganese nodules, and in the waters above. DNA samples from the animals collected will also aid in the identification and description of the many new species, and to assess their occurrence across the abyssal Pacific Ocean.

“Another unexpected find was a dramatic difference in the abundance of manganese nodules and animals living on them over surprisingly short distances of a few hundred miles across the abyssal plain,” said Smith.

—By Marcie Grabowski