A Complication of a Retropharyngeal Abscess

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 7, Case 10

Orn-Usa Lisa Boonprakong, Medical Student

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

This is an 8 month old male who was in his usual

state of health until 2 weeks ago when he developed

fever (38 to 39 degrees C), intermittent cough,

congestion, and increased secretions. He was treated

with antibiotics by his primary care physician. One

week ago, he developed hives with wheezing, stridor

and tachypnea. He was treated with albuterol and

prednisolone with subsequent relief. Three days ago,

he then developed a dry cough, shallow respirations,

and apparent stiffness of his neck with an inability to

straighten his neck or bring his head to midline. He

was most comfortable in the position of being upright or

lying on his side. Gradually, his respirations became

"noisy and gurgly". He now presents to a rural

emergency department with worsening stridor. His past

medical history is unremarkable.

Exam: VS T39, P120, R40, oxygen saturation

98-100% on RA. He is somewhat irritable but easily

arousable and consolable, holding his neck in a solitary

position. Eyes normal. Nares are clear without

drainage. Tympanic membranes normal. His oral

cavity is clear, with moist mucosa. The posterior

pharynx is very full, with slightly enlarged tonsils

bilaterally. His neck is slightly stiff with discomfort

experienced on movement. There is right-sided

cervical lymphadenopathy, with slight tracheal

deviation to the right. Breath sounds demonstrate

moderate stridor with slight coarse rhonchi. Heart

regular rate and rhythm, without murmur. Abdomen is

soft and flat, normal bowel sounds, no organomegaly.

His extremities are warm with normal capillary refill.

His skin demonstrates no rashes or lesions.

Radiographs of his chest and neck are ordered.

Can you identify the abnormalities on his radiographs.

View his chest and lateral neck radiographs.

His chest radiographs

His lateral neck radiograph

His lateral neck radiograph

His lateral neck radiograph shows severe

prevertebral soft tissue swelling with extension

inferiorly. The width of the prevertebral soft tissue

should normally be about half the width of a vertebral

body (see Case 10 of Volume 1). In this case, it is very

wide. His chest radiograph demonstrates a widened

mediastinum and shift of the airway to the right.

He is intubated using rapid sequence intubation to

ensure a stable airway during air transport to a

children's hospital for further management. A CT scan

of the chest is obtained prior to transport.

View his chest CT scan.

His lateral neck radiograph shows severe

prevertebral soft tissue swelling with extension

inferiorly. The width of the prevertebral soft tissue

should normally be about half the width of a vertebral

body (see Case 10 of Volume 1). In this case, it is very

wide. His chest radiograph demonstrates a widened

mediastinum and shift of the airway to the right.

He is intubated using rapid sequence intubation to

ensure a stable airway during air transport to a

children's hospital for further management. A CT scan

of the chest is obtained prior to transport.

View his chest CT scan.

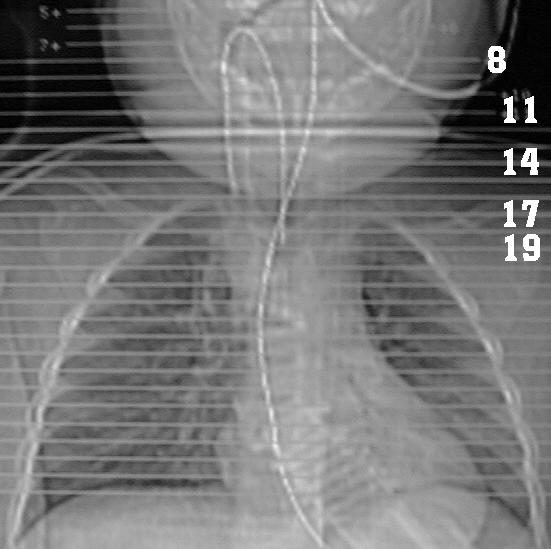

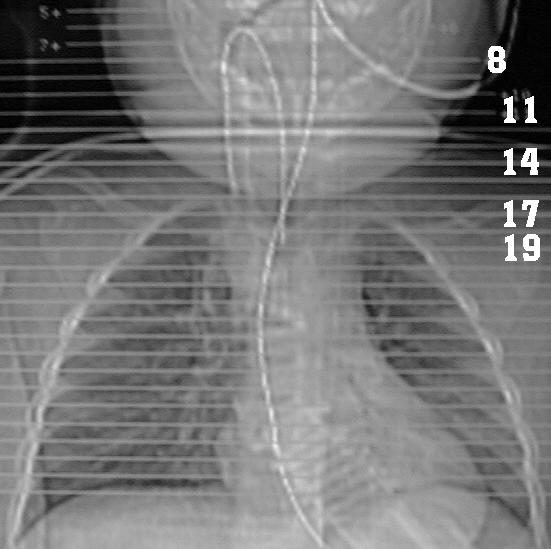

Scout view showing image cut levels

Scout view showing image cut levels

The CT scan demonstrates a retropharyngeal

abscess that extends towards the posterior

mediastinum to the level of the aortic arch. This image

shows the abscess (black arrows) on cuts 8, 11, 14, 17

and 19 from his CT study. The level of these cuts are

demonstrated on the scout view. At a level

through his mouth, cut 8 shows the large abscess

cavity which bulges anteriorly. At chin level, cut 11

shows the abscess with a typical enhancing rim. Cut

14 shows the abscess at mid-neck level. Cut 17 shows

extension of the abscess into the mediastinum at the

level of the lung apices. Cut 19 shows extension of the

abscess into the mediastinum at the level of the upper

lobes.

He was initially placed on clindamycin and

cefotaxime. He underwent a surgical drainage

procedure for both the retropharyngeal and mediastinal

abscesses. Cultures of the pus grew Group A beta

hemolytic streptococci, at which time he was changed

to penicillin.

Discussion

The retropharyngeal space is a potential space in

the deep neck that is bordered by the buccopharyngeal

fascia anteriorly, the prevertebral fascia posteriorly,

and the carotid sheath laterally. An infection

developing in this space could potentially spread into

the mediastinum and other deep neck compartments.

In the pediatric population, this space contains lymph

nodes draining the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses,

nasal cavity, and soft palate. These retropharyngeal

nodes atrophy at puberty making abscess formation

less likely in teens and adults.

Retropharyngeal abscesses are most commonly

present in children less than 3 years of age. In the

pediatric population, retropharyngeal abscesses

typically result from upper respiratory infections

(particularly oropharyngeal infections) with suppurative

cervical lymphadenopathy, whereas in adults they

normally occur secondary to trauma to the oropharynx,

iatrogenic instrumentation, foreign bodies, or dental

infections.

Initial antimicrobial empiric therapy is directed

towards the aerobic and anaerobic flora of the

nasopharynx. Common aerobes are Staphylococcus

aureas, alpha hemolytic and non-hemolytic

streptococci, Haemophilus species, and group A

beta-hemolytic Streptococci. Common anaerobes are

bacteriodes, peptostreptococci, and fusobacteria.

During surgical drainage, an aspirate of the pus is

obtained for specific determination of the causative

microorganism(s).

Signs and symptoms include high fever, dysphagia,

odynophagia, drooling, neck/cervical rigidity and

swelling, anorexia, a "hot potato"/muffled voice,

bulging/fluctuance of the posterior pharyngeal wall

which is usually difficult to see. Dysphagia and

drooling are more common indicators of actual upper

airway involvement, whereas inspiratory stridor is less

common.

When suspected clinically, a lateral neck radiograph

is usually adequate to diagnose the presence of a

retropharyngeal abscess. A true lateral neck x-ray

should be taken in extension (cervical spine lordosis

should be visible on the radiograph) and inspiration.

The anteroposterior diameter of the prevertebral soft

tissues should not exceed the width of the vertebral

bodies. With a retropharyngeal abscess, a classic

widened soft tissue shadow anterior to the cervical

vertebrae is seen with a normal epiglottis and

aryepiglottic folds.

A CT scan is diagnostically useful to distinguish

between abscess (requiring surgical drainage) and a

phlegmon cellulitis (which may not require surgical

drainage), indicating the extent of abscess involvement,

localizing the lesion prior to surgical intervention, and

to differentiate which deep neck spaces are involved

(see Case 1 of Volume 5).

Retropharyngeal abscess is in the differential

diagnosis of a febrile infant with airway obstruction.

Usually a high index of suspicion is needed to identify a

child with a retropharyngeal abscess. The presentation

of a stiff neck can initially be misdiagnosed as

meningitis, and inspiratory stridor may mimic croup or

epiglottitis.

Treatment of a retropharyngeal abscess requiers

the maintainance of a stable airway, thus, endotracheal

intubation may be necessary if airway compromise is

present. IV antibiotics are required. Surgical drainage

is usually required in a true abscess. Perioral drainage

is normally adequate for uncomplicated infections that

have not entered other deep neck spaces or affected

the airway. External drainage, along the anterior

aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, between the carotid

sheath and inferior constrictor muscle, is usually

required for the more severe infections that have

spread to other compartments. Antibiotics should

initially cover the common microbes (i.e. streptococci,

staph aureus, anaerobes).

Complications include mediastinitis and mediastinal

abscess secondary to spread from the retropharyngeal

space (being contiguous with the mediastinum), airway

obstruction, and rupture of the abscess with potential

aspiration of pus and pneumonia. Mediastinitis is a

rare and life-threatening complication with a mortality

rate as high as 40%. Most cases of reported

suppurative mediastinitis have been secondary to

esophageal perforation (traumatic or nontraumatic) and

after median sternotomy.

When managing a patient with a retropharyngeal

abscess, physicians should consider the possibility of

this complication. Chest radiographs may be

necessary to rule out mediastinal or pulmonary

involvement. A CT scan will also be helpful in

determining the extent of the abscess. The extension

of the infection of the neck to the mediastinum has

been attributed to synergistic necrotizing bacterial

growth, negative intrathoracic pressure, and dependent

drainage from the neck to the mediastinum. The high

occurrence of mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora in

retropharyngeal abscess complicated by mediastinitis

may account for the necrotizing nature of this type of

infection. Immediate diagnosis and surgical drainage

of the retropharyngeal and mediastinal abscesses are

essential for treatment.

References

1. Gaglani MJ, Morven SE. Clinical Indicators of

Childhood Retropharyngeal Abscess. Am J Emerg Med

1995;13(3):333-335.

2. Goldenerg D, Gotz A, Joachms HZ.

Retropharyngeal Abscess: a Clinical Review. J

Laryngol Otol 1997;111:546-550.

3. Lalakea ML, Messner AH. Retropharyngeal

Abscess Management in Children: Current Practices.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;121(4):398-405.

4. Sztajnbok J, Grassi MS, Katayama DM, Troster

EJ. Descending Suppurative Mediastinitis: Nonsurgical

Approach to this Unusual Complication of

Retropharyngeal Abscesses in Childhood. Pediatr

Emerg Care 1999;15(5):341-343.

The CT scan demonstrates a retropharyngeal

abscess that extends towards the posterior

mediastinum to the level of the aortic arch. This image

shows the abscess (black arrows) on cuts 8, 11, 14, 17

and 19 from his CT study. The level of these cuts are

demonstrated on the scout view. At a level

through his mouth, cut 8 shows the large abscess

cavity which bulges anteriorly. At chin level, cut 11

shows the abscess with a typical enhancing rim. Cut

14 shows the abscess at mid-neck level. Cut 17 shows

extension of the abscess into the mediastinum at the

level of the lung apices. Cut 19 shows extension of the

abscess into the mediastinum at the level of the upper

lobes.

He was initially placed on clindamycin and

cefotaxime. He underwent a surgical drainage

procedure for both the retropharyngeal and mediastinal

abscesses. Cultures of the pus grew Group A beta

hemolytic streptococci, at which time he was changed

to penicillin.

Discussion

The retropharyngeal space is a potential space in

the deep neck that is bordered by the buccopharyngeal

fascia anteriorly, the prevertebral fascia posteriorly,

and the carotid sheath laterally. An infection

developing in this space could potentially spread into

the mediastinum and other deep neck compartments.

In the pediatric population, this space contains lymph

nodes draining the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses,

nasal cavity, and soft palate. These retropharyngeal

nodes atrophy at puberty making abscess formation

less likely in teens and adults.

Retropharyngeal abscesses are most commonly

present in children less than 3 years of age. In the

pediatric population, retropharyngeal abscesses

typically result from upper respiratory infections

(particularly oropharyngeal infections) with suppurative

cervical lymphadenopathy, whereas in adults they

normally occur secondary to trauma to the oropharynx,

iatrogenic instrumentation, foreign bodies, or dental

infections.

Initial antimicrobial empiric therapy is directed

towards the aerobic and anaerobic flora of the

nasopharynx. Common aerobes are Staphylococcus

aureas, alpha hemolytic and non-hemolytic

streptococci, Haemophilus species, and group A

beta-hemolytic Streptococci. Common anaerobes are

bacteriodes, peptostreptococci, and fusobacteria.

During surgical drainage, an aspirate of the pus is

obtained for specific determination of the causative

microorganism(s).

Signs and symptoms include high fever, dysphagia,

odynophagia, drooling, neck/cervical rigidity and

swelling, anorexia, a "hot potato"/muffled voice,

bulging/fluctuance of the posterior pharyngeal wall

which is usually difficult to see. Dysphagia and

drooling are more common indicators of actual upper

airway involvement, whereas inspiratory stridor is less

common.

When suspected clinically, a lateral neck radiograph

is usually adequate to diagnose the presence of a

retropharyngeal abscess. A true lateral neck x-ray

should be taken in extension (cervical spine lordosis

should be visible on the radiograph) and inspiration.

The anteroposterior diameter of the prevertebral soft

tissues should not exceed the width of the vertebral

bodies. With a retropharyngeal abscess, a classic

widened soft tissue shadow anterior to the cervical

vertebrae is seen with a normal epiglottis and

aryepiglottic folds.

A CT scan is diagnostically useful to distinguish

between abscess (requiring surgical drainage) and a

phlegmon cellulitis (which may not require surgical

drainage), indicating the extent of abscess involvement,

localizing the lesion prior to surgical intervention, and

to differentiate which deep neck spaces are involved

(see Case 1 of Volume 5).

Retropharyngeal abscess is in the differential

diagnosis of a febrile infant with airway obstruction.

Usually a high index of suspicion is needed to identify a

child with a retropharyngeal abscess. The presentation

of a stiff neck can initially be misdiagnosed as

meningitis, and inspiratory stridor may mimic croup or

epiglottitis.

Treatment of a retropharyngeal abscess requiers

the maintainance of a stable airway, thus, endotracheal

intubation may be necessary if airway compromise is

present. IV antibiotics are required. Surgical drainage

is usually required in a true abscess. Perioral drainage

is normally adequate for uncomplicated infections that

have not entered other deep neck spaces or affected

the airway. External drainage, along the anterior

aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, between the carotid

sheath and inferior constrictor muscle, is usually

required for the more severe infections that have

spread to other compartments. Antibiotics should

initially cover the common microbes (i.e. streptococci,

staph aureus, anaerobes).

Complications include mediastinitis and mediastinal

abscess secondary to spread from the retropharyngeal

space (being contiguous with the mediastinum), airway

obstruction, and rupture of the abscess with potential

aspiration of pus and pneumonia. Mediastinitis is a

rare and life-threatening complication with a mortality

rate as high as 40%. Most cases of reported

suppurative mediastinitis have been secondary to

esophageal perforation (traumatic or nontraumatic) and

after median sternotomy.

When managing a patient with a retropharyngeal

abscess, physicians should consider the possibility of

this complication. Chest radiographs may be

necessary to rule out mediastinal or pulmonary

involvement. A CT scan will also be helpful in

determining the extent of the abscess. The extension

of the infection of the neck to the mediastinum has

been attributed to synergistic necrotizing bacterial

growth, negative intrathoracic pressure, and dependent

drainage from the neck to the mediastinum. The high

occurrence of mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora in

retropharyngeal abscess complicated by mediastinitis

may account for the necrotizing nature of this type of

infection. Immediate diagnosis and surgical drainage

of the retropharyngeal and mediastinal abscesses are

essential for treatment.

References

1. Gaglani MJ, Morven SE. Clinical Indicators of

Childhood Retropharyngeal Abscess. Am J Emerg Med

1995;13(3):333-335.

2. Goldenerg D, Gotz A, Joachms HZ.

Retropharyngeal Abscess: a Clinical Review. J

Laryngol Otol 1997;111:546-550.

3. Lalakea ML, Messner AH. Retropharyngeal

Abscess Management in Children: Current Practices.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;121(4):398-405.

4. Sztajnbok J, Grassi MS, Katayama DM, Troster

EJ. Descending Suppurative Mediastinitis: Nonsurgical

Approach to this Unusual Complication of

Retropharyngeal Abscesses in Childhood. Pediatr

Emerg Care 1999;15(5):341-343.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

His lateral neck radiograph

His lateral neck radiograph

His lateral neck radiograph shows severe

prevertebral soft tissue swelling with extension

inferiorly. The width of the prevertebral soft tissue

should normally be about half the width of a vertebral

body (see Case 10 of Volume 1). In this case, it is very

wide. His chest radiograph demonstrates a widened

mediastinum and shift of the airway to the right.

He is intubated using rapid sequence intubation to

ensure a stable airway during air transport to a

children's hospital for further management. A CT scan

of the chest is obtained prior to transport.

View his chest CT scan.

His lateral neck radiograph shows severe

prevertebral soft tissue swelling with extension

inferiorly. The width of the prevertebral soft tissue

should normally be about half the width of a vertebral

body (see Case 10 of Volume 1). In this case, it is very

wide. His chest radiograph demonstrates a widened

mediastinum and shift of the airway to the right.

He is intubated using rapid sequence intubation to

ensure a stable airway during air transport to a

children's hospital for further management. A CT scan

of the chest is obtained prior to transport.

View his chest CT scan.

Scout view showing image cut levels

Scout view showing image cut levels

The CT scan demonstrates a retropharyngeal

abscess that extends towards the posterior

mediastinum to the level of the aortic arch. This image

shows the abscess (black arrows) on cuts 8, 11, 14, 17

and 19 from his CT study. The level of these cuts are

demonstrated on the scout view. At a level

through his mouth, cut 8 shows the large abscess

cavity which bulges anteriorly. At chin level, cut 11

shows the abscess with a typical enhancing rim. Cut

14 shows the abscess at mid-neck level. Cut 17 shows

extension of the abscess into the mediastinum at the

level of the lung apices. Cut 19 shows extension of the

abscess into the mediastinum at the level of the upper

lobes.

He was initially placed on clindamycin and

cefotaxime. He underwent a surgical drainage

procedure for both the retropharyngeal and mediastinal

abscesses. Cultures of the pus grew Group A beta

hemolytic streptococci, at which time he was changed

to penicillin.

Discussion

The retropharyngeal space is a potential space in

the deep neck that is bordered by the buccopharyngeal

fascia anteriorly, the prevertebral fascia posteriorly,

and the carotid sheath laterally. An infection

developing in this space could potentially spread into

the mediastinum and other deep neck compartments.

In the pediatric population, this space contains lymph

nodes draining the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses,

nasal cavity, and soft palate. These retropharyngeal

nodes atrophy at puberty making abscess formation

less likely in teens and adults.

Retropharyngeal abscesses are most commonly

present in children less than 3 years of age. In the

pediatric population, retropharyngeal abscesses

typically result from upper respiratory infections

(particularly oropharyngeal infections) with suppurative

cervical lymphadenopathy, whereas in adults they

normally occur secondary to trauma to the oropharynx,

iatrogenic instrumentation, foreign bodies, or dental

infections.

Initial antimicrobial empiric therapy is directed

towards the aerobic and anaerobic flora of the

nasopharynx. Common aerobes are Staphylococcus

aureas, alpha hemolytic and non-hemolytic

streptococci, Haemophilus species, and group A

beta-hemolytic Streptococci. Common anaerobes are

bacteriodes, peptostreptococci, and fusobacteria.

During surgical drainage, an aspirate of the pus is

obtained for specific determination of the causative

microorganism(s).

Signs and symptoms include high fever, dysphagia,

odynophagia, drooling, neck/cervical rigidity and

swelling, anorexia, a "hot potato"/muffled voice,

bulging/fluctuance of the posterior pharyngeal wall

which is usually difficult to see. Dysphagia and

drooling are more common indicators of actual upper

airway involvement, whereas inspiratory stridor is less

common.

When suspected clinically, a lateral neck radiograph

is usually adequate to diagnose the presence of a

retropharyngeal abscess. A true lateral neck x-ray

should be taken in extension (cervical spine lordosis

should be visible on the radiograph) and inspiration.

The anteroposterior diameter of the prevertebral soft

tissues should not exceed the width of the vertebral

bodies. With a retropharyngeal abscess, a classic

widened soft tissue shadow anterior to the cervical

vertebrae is seen with a normal epiglottis and

aryepiglottic folds.

A CT scan is diagnostically useful to distinguish

between abscess (requiring surgical drainage) and a

phlegmon cellulitis (which may not require surgical

drainage), indicating the extent of abscess involvement,

localizing the lesion prior to surgical intervention, and

to differentiate which deep neck spaces are involved

(see Case 1 of Volume 5).

Retropharyngeal abscess is in the differential

diagnosis of a febrile infant with airway obstruction.

Usually a high index of suspicion is needed to identify a

child with a retropharyngeal abscess. The presentation

of a stiff neck can initially be misdiagnosed as

meningitis, and inspiratory stridor may mimic croup or

epiglottitis.

Treatment of a retropharyngeal abscess requiers

the maintainance of a stable airway, thus, endotracheal

intubation may be necessary if airway compromise is

present. IV antibiotics are required. Surgical drainage

is usually required in a true abscess. Perioral drainage

is normally adequate for uncomplicated infections that

have not entered other deep neck spaces or affected

the airway. External drainage, along the anterior

aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, between the carotid

sheath and inferior constrictor muscle, is usually

required for the more severe infections that have

spread to other compartments. Antibiotics should

initially cover the common microbes (i.e. streptococci,

staph aureus, anaerobes).

Complications include mediastinitis and mediastinal

abscess secondary to spread from the retropharyngeal

space (being contiguous with the mediastinum), airway

obstruction, and rupture of the abscess with potential

aspiration of pus and pneumonia. Mediastinitis is a

rare and life-threatening complication with a mortality

rate as high as 40%. Most cases of reported

suppurative mediastinitis have been secondary to

esophageal perforation (traumatic or nontraumatic) and

after median sternotomy.

When managing a patient with a retropharyngeal

abscess, physicians should consider the possibility of

this complication. Chest radiographs may be

necessary to rule out mediastinal or pulmonary

involvement. A CT scan will also be helpful in

determining the extent of the abscess. The extension

of the infection of the neck to the mediastinum has

been attributed to synergistic necrotizing bacterial

growth, negative intrathoracic pressure, and dependent

drainage from the neck to the mediastinum. The high

occurrence of mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora in

retropharyngeal abscess complicated by mediastinitis

may account for the necrotizing nature of this type of

infection. Immediate diagnosis and surgical drainage

of the retropharyngeal and mediastinal abscesses are

essential for treatment.

References

1. Gaglani MJ, Morven SE. Clinical Indicators of

Childhood Retropharyngeal Abscess. Am J Emerg Med

1995;13(3):333-335.

2. Goldenerg D, Gotz A, Joachms HZ.

Retropharyngeal Abscess: a Clinical Review. J

Laryngol Otol 1997;111:546-550.

3. Lalakea ML, Messner AH. Retropharyngeal

Abscess Management in Children: Current Practices.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;121(4):398-405.

4. Sztajnbok J, Grassi MS, Katayama DM, Troster

EJ. Descending Suppurative Mediastinitis: Nonsurgical

Approach to this Unusual Complication of

Retropharyngeal Abscesses in Childhood. Pediatr

Emerg Care 1999;15(5):341-343.

The CT scan demonstrates a retropharyngeal

abscess that extends towards the posterior

mediastinum to the level of the aortic arch. This image

shows the abscess (black arrows) on cuts 8, 11, 14, 17

and 19 from his CT study. The level of these cuts are

demonstrated on the scout view. At a level

through his mouth, cut 8 shows the large abscess

cavity which bulges anteriorly. At chin level, cut 11

shows the abscess with a typical enhancing rim. Cut

14 shows the abscess at mid-neck level. Cut 17 shows

extension of the abscess into the mediastinum at the

level of the lung apices. Cut 19 shows extension of the

abscess into the mediastinum at the level of the upper

lobes.

He was initially placed on clindamycin and

cefotaxime. He underwent a surgical drainage

procedure for both the retropharyngeal and mediastinal

abscesses. Cultures of the pus grew Group A beta

hemolytic streptococci, at which time he was changed

to penicillin.

Discussion

The retropharyngeal space is a potential space in

the deep neck that is bordered by the buccopharyngeal

fascia anteriorly, the prevertebral fascia posteriorly,

and the carotid sheath laterally. An infection

developing in this space could potentially spread into

the mediastinum and other deep neck compartments.

In the pediatric population, this space contains lymph

nodes draining the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses,

nasal cavity, and soft palate. These retropharyngeal

nodes atrophy at puberty making abscess formation

less likely in teens and adults.

Retropharyngeal abscesses are most commonly

present in children less than 3 years of age. In the

pediatric population, retropharyngeal abscesses

typically result from upper respiratory infections

(particularly oropharyngeal infections) with suppurative

cervical lymphadenopathy, whereas in adults they

normally occur secondary to trauma to the oropharynx,

iatrogenic instrumentation, foreign bodies, or dental

infections.

Initial antimicrobial empiric therapy is directed

towards the aerobic and anaerobic flora of the

nasopharynx. Common aerobes are Staphylococcus

aureas, alpha hemolytic and non-hemolytic

streptococci, Haemophilus species, and group A

beta-hemolytic Streptococci. Common anaerobes are

bacteriodes, peptostreptococci, and fusobacteria.

During surgical drainage, an aspirate of the pus is

obtained for specific determination of the causative

microorganism(s).

Signs and symptoms include high fever, dysphagia,

odynophagia, drooling, neck/cervical rigidity and

swelling, anorexia, a "hot potato"/muffled voice,

bulging/fluctuance of the posterior pharyngeal wall

which is usually difficult to see. Dysphagia and

drooling are more common indicators of actual upper

airway involvement, whereas inspiratory stridor is less

common.

When suspected clinically, a lateral neck radiograph

is usually adequate to diagnose the presence of a

retropharyngeal abscess. A true lateral neck x-ray

should be taken in extension (cervical spine lordosis

should be visible on the radiograph) and inspiration.

The anteroposterior diameter of the prevertebral soft

tissues should not exceed the width of the vertebral

bodies. With a retropharyngeal abscess, a classic

widened soft tissue shadow anterior to the cervical

vertebrae is seen with a normal epiglottis and

aryepiglottic folds.

A CT scan is diagnostically useful to distinguish

between abscess (requiring surgical drainage) and a

phlegmon cellulitis (which may not require surgical

drainage), indicating the extent of abscess involvement,

localizing the lesion prior to surgical intervention, and

to differentiate which deep neck spaces are involved

(see Case 1 of Volume 5).

Retropharyngeal abscess is in the differential

diagnosis of a febrile infant with airway obstruction.

Usually a high index of suspicion is needed to identify a

child with a retropharyngeal abscess. The presentation

of a stiff neck can initially be misdiagnosed as

meningitis, and inspiratory stridor may mimic croup or

epiglottitis.

Treatment of a retropharyngeal abscess requiers

the maintainance of a stable airway, thus, endotracheal

intubation may be necessary if airway compromise is

present. IV antibiotics are required. Surgical drainage

is usually required in a true abscess. Perioral drainage

is normally adequate for uncomplicated infections that

have not entered other deep neck spaces or affected

the airway. External drainage, along the anterior

aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, between the carotid

sheath and inferior constrictor muscle, is usually

required for the more severe infections that have

spread to other compartments. Antibiotics should

initially cover the common microbes (i.e. streptococci,

staph aureus, anaerobes).

Complications include mediastinitis and mediastinal

abscess secondary to spread from the retropharyngeal

space (being contiguous with the mediastinum), airway

obstruction, and rupture of the abscess with potential

aspiration of pus and pneumonia. Mediastinitis is a

rare and life-threatening complication with a mortality

rate as high as 40%. Most cases of reported

suppurative mediastinitis have been secondary to

esophageal perforation (traumatic or nontraumatic) and

after median sternotomy.

When managing a patient with a retropharyngeal

abscess, physicians should consider the possibility of

this complication. Chest radiographs may be

necessary to rule out mediastinal or pulmonary

involvement. A CT scan will also be helpful in

determining the extent of the abscess. The extension

of the infection of the neck to the mediastinum has

been attributed to synergistic necrotizing bacterial

growth, negative intrathoracic pressure, and dependent

drainage from the neck to the mediastinum. The high

occurrence of mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora in

retropharyngeal abscess complicated by mediastinitis

may account for the necrotizing nature of this type of

infection. Immediate diagnosis and surgical drainage

of the retropharyngeal and mediastinal abscesses are

essential for treatment.

References

1. Gaglani MJ, Morven SE. Clinical Indicators of

Childhood Retropharyngeal Abscess. Am J Emerg Med

1995;13(3):333-335.

2. Goldenerg D, Gotz A, Joachms HZ.

Retropharyngeal Abscess: a Clinical Review. J

Laryngol Otol 1997;111:546-550.

3. Lalakea ML, Messner AH. Retropharyngeal

Abscess Management in Children: Current Practices.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;121(4):398-405.

4. Sztajnbok J, Grassi MS, Katayama DM, Troster

EJ. Descending Suppurative Mediastinitis: Nonsurgical

Approach to this Unusual Complication of

Retropharyngeal Abscesses in Childhood. Pediatr

Emerg Care 1999;15(5):341-343.