Infant Skull Fractures

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 5, Case 9

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

Plain film radiographs of the skull are obtained in

limited circumstances. In most instances, CT scanning

of the head is more useful. Some hospitals and clinics

do not have easy access to CT scanning and hence,

they rely more on the use of clinical assessment, plain

film skull radiographs, and judicious referral to a center

with a CT scanner. Interpreting skull radiographs in

infants can be difficult since their skulls have many

normal lucencies. Sutures are generally sinusoidal in

appearance and in their standard anatomic locations

(coronal, sagittal, and labdoidal). Fractures are rarely

sinusoidal. Fractures are usually linear, stellate, or

depressed.

View normal skull radiograph.

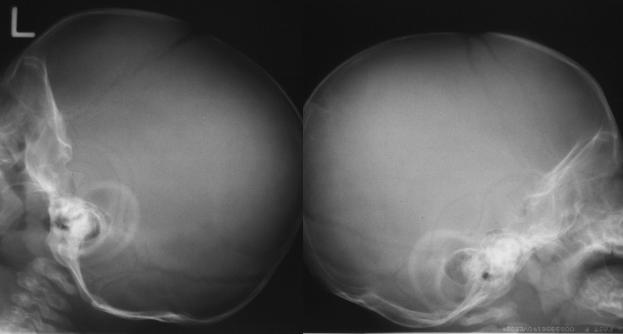

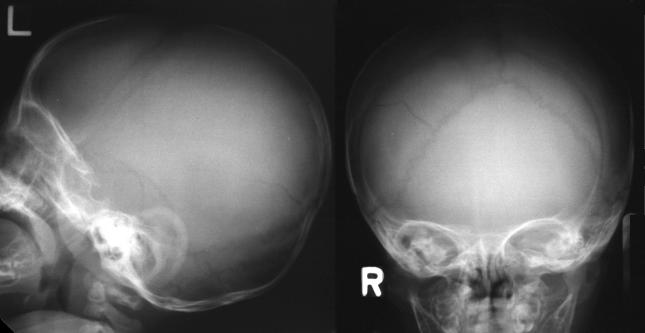

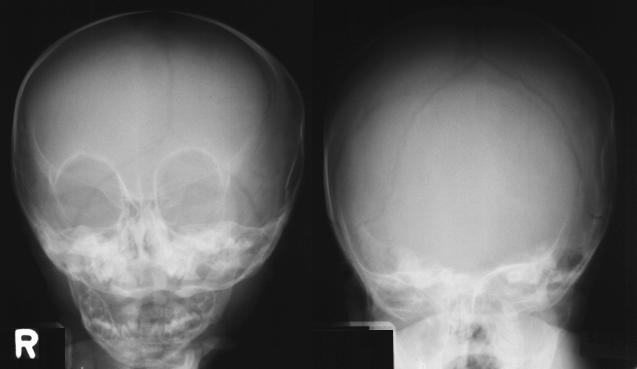

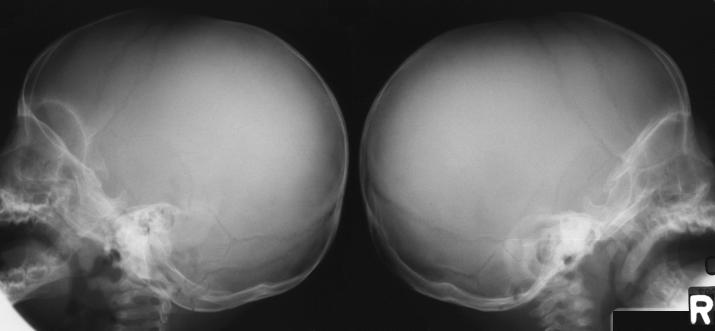

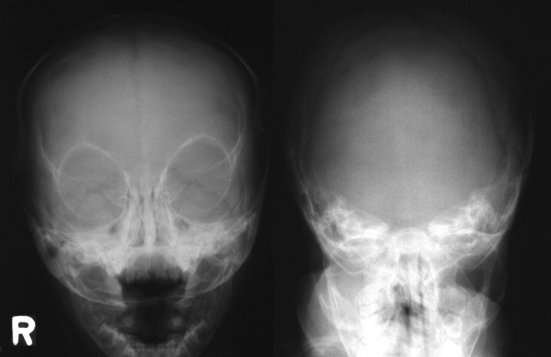

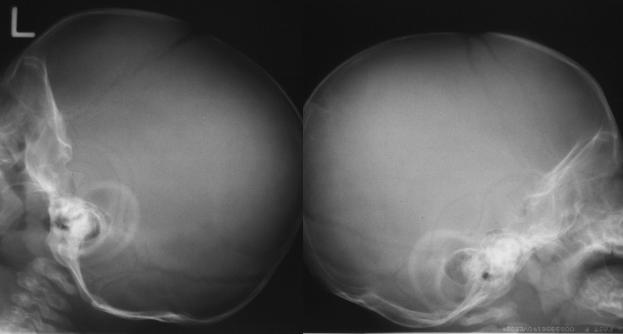

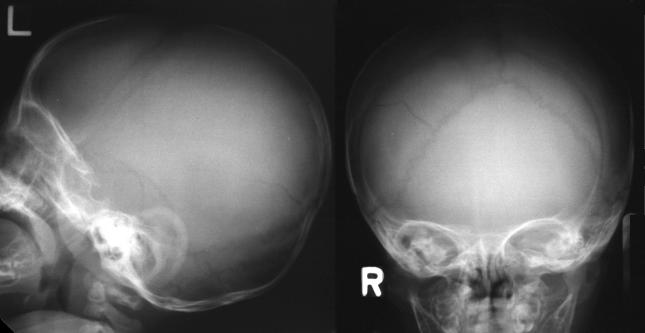

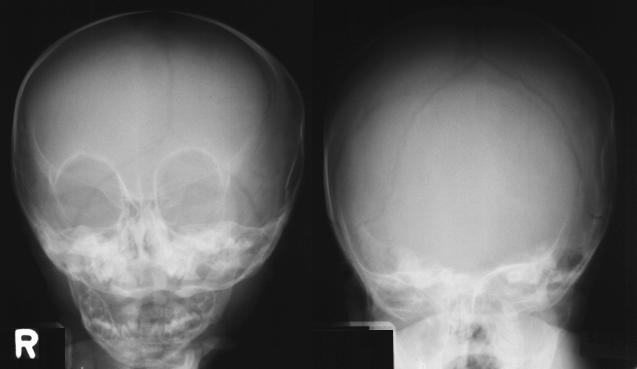

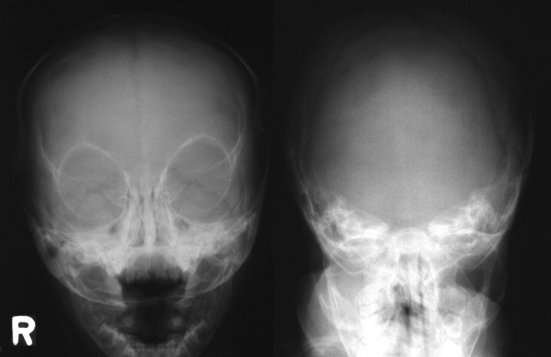

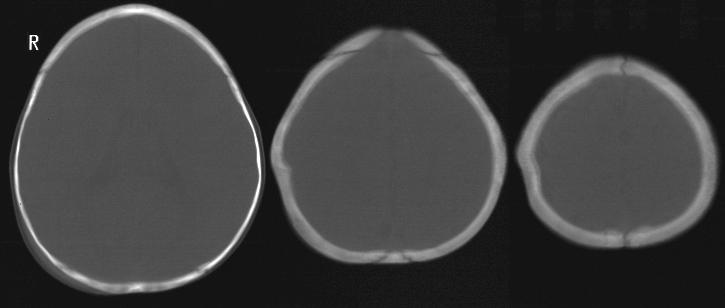

Four standard views are often obtained. An AP

view, a Towne's view, and two lateral views. The

Towne's view is an AP view with the neck flexed

forward. Two lateral views can be more optimal than a

single lateral view to permit the film to focus on one

side at a time.

Locate the coronal, sagittal, and lambdoidal sutures

on these skull radiographs. In addition to these major

sutures, the anterior fontanelle is often visible. A suture

extends from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle

into the frontal bone. Two smaller sutures on each side

of the skull are present in the lower skull adjacent to the

mastoid; the parietomastoid suture and the

occipitomastoid suture.

View the locations of these sutures.

Four standard views are often obtained. An AP

view, a Towne's view, and two lateral views. The

Towne's view is an AP view with the neck flexed

forward. Two lateral views can be more optimal than a

single lateral view to permit the film to focus on one

side at a time.

Locate the coronal, sagittal, and lambdoidal sutures

on these skull radiographs. In addition to these major

sutures, the anterior fontanelle is often visible. A suture

extends from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle

into the frontal bone. Two smaller sutures on each side

of the skull are present in the lower skull adjacent to the

mastoid; the parietomastoid suture and the

occipitomastoid suture.

View the locations of these sutures.

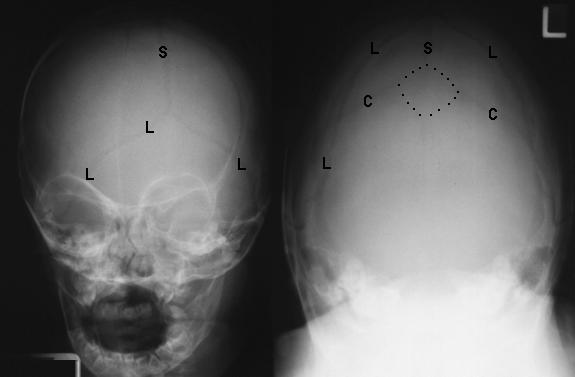

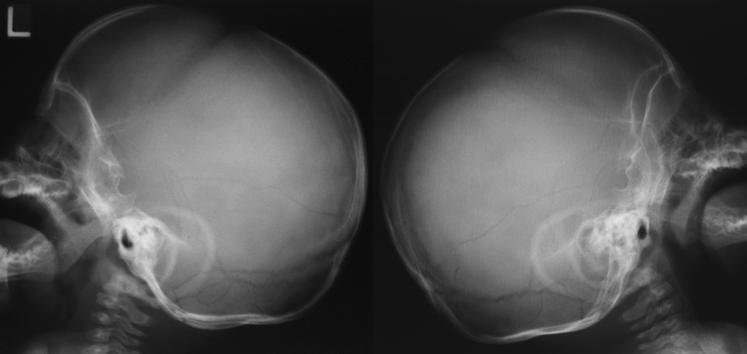

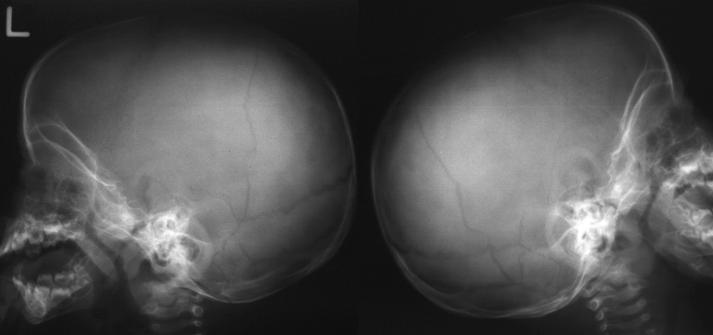

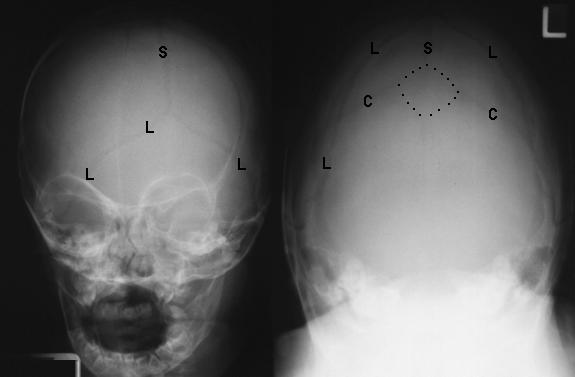

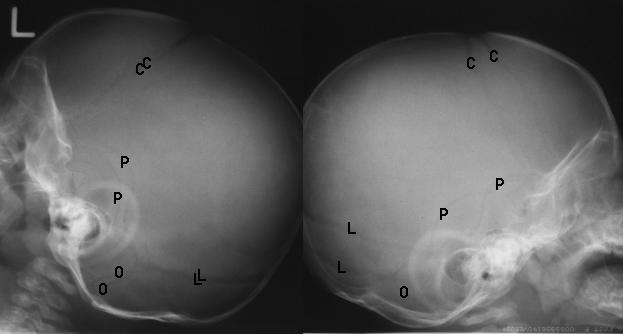

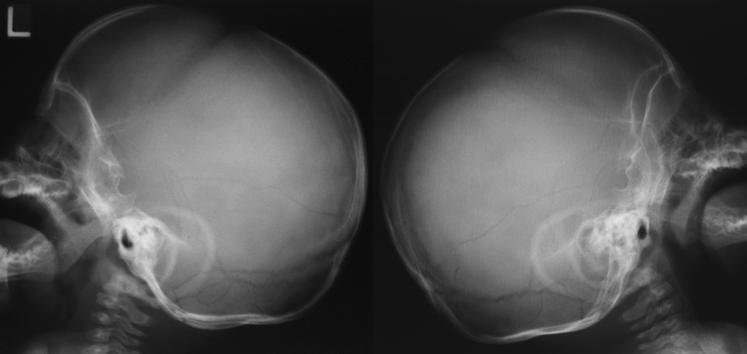

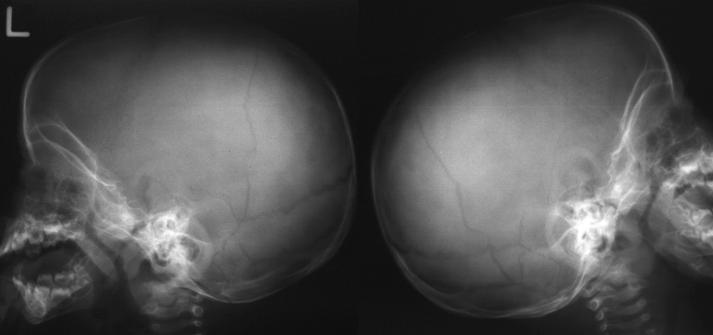

C - Coronal

S - Sagittal

L - Lambdoidal

P - Parietomastoid (squamosal)

O - Occipitomastoid

The anterior fontanelle is outlined in the broken line.

Note that a suture extends anteriorly into the frontal

bone from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle.

Linear skull fractures are rarely associated with the

need for neurosurgical intervention. They will often

present to an acute care clinic or emergency

department several days after the injury with a

subgaleal hematoma (soft swelling on the side of the

head) as a chief complaint. These are benign and

should not be aspirated unless an infection is present.

Parietal skull fractures which cross the path of the

middle meningeal artery or other major vessels may be

associated with epidural or other types of intracranial

hemorrhage. In young children, the middle meningeal

artery does not groove into the bone as it does in adults

and thus, laceration of the middle meningeal artery is

less likely to occur (compared to adults) with a parietal

skull fracture. Roughly half of the epidural hematomas

in children occur in the absence of skull fractures.

Thus, plain film skull radiographs should not be used as

a routine screening measure to determine risk of

intracranial hemorrhage. CT scanning is more effective

at ruling out cerebral hemorrhages.

Neither CT nor plain film skull radiographs are highly

reliable in ruling out a basilar skull fracture. Such

fractures are difficult to see on CT scans and plain film

skull radiographs. This diagnosis is often made

clinically (nasal CSF leak, CSF otorrhea,

hemotympanum, Battle's sign, etc.) and then confirmed

on fine or angled CT cuts, or MRI.

Widely separated linear skull fractures (widely

diastatic) are associated with a higher risk of subdural

hematoma and an increased risk of developing

leptomeningeal cysts. The follow-up radiograph one

month later may show a "growing" fracture that results

from a meningeal laceration. This results in a bulging

leptomeningeal sac that causes erosion of the overlying

skull and an eventual skull defect if it is not repaired.

Depressed skull fractures may be evident on plain

radiographs, however, CT scanning is better able to

determine the extent of depression.

View the plain film skull radiographs to test your skill

in interpreting these radiographs.

View Case B.

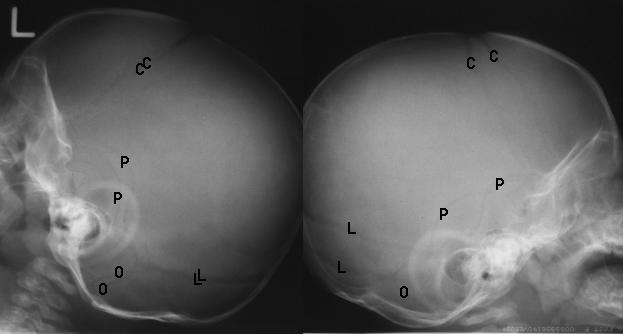

C - Coronal

S - Sagittal

L - Lambdoidal

P - Parietomastoid (squamosal)

O - Occipitomastoid

The anterior fontanelle is outlined in the broken line.

Note that a suture extends anteriorly into the frontal

bone from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle.

Linear skull fractures are rarely associated with the

need for neurosurgical intervention. They will often

present to an acute care clinic or emergency

department several days after the injury with a

subgaleal hematoma (soft swelling on the side of the

head) as a chief complaint. These are benign and

should not be aspirated unless an infection is present.

Parietal skull fractures which cross the path of the

middle meningeal artery or other major vessels may be

associated with epidural or other types of intracranial

hemorrhage. In young children, the middle meningeal

artery does not groove into the bone as it does in adults

and thus, laceration of the middle meningeal artery is

less likely to occur (compared to adults) with a parietal

skull fracture. Roughly half of the epidural hematomas

in children occur in the absence of skull fractures.

Thus, plain film skull radiographs should not be used as

a routine screening measure to determine risk of

intracranial hemorrhage. CT scanning is more effective

at ruling out cerebral hemorrhages.

Neither CT nor plain film skull radiographs are highly

reliable in ruling out a basilar skull fracture. Such

fractures are difficult to see on CT scans and plain film

skull radiographs. This diagnosis is often made

clinically (nasal CSF leak, CSF otorrhea,

hemotympanum, Battle's sign, etc.) and then confirmed

on fine or angled CT cuts, or MRI.

Widely separated linear skull fractures (widely

diastatic) are associated with a higher risk of subdural

hematoma and an increased risk of developing

leptomeningeal cysts. The follow-up radiograph one

month later may show a "growing" fracture that results

from a meningeal laceration. This results in a bulging

leptomeningeal sac that causes erosion of the overlying

skull and an eventual skull defect if it is not repaired.

Depressed skull fractures may be evident on plain

radiographs, however, CT scanning is better able to

determine the extent of depression.

View the plain film skull radiographs to test your skill

in interpreting these radiographs.

View Case B.

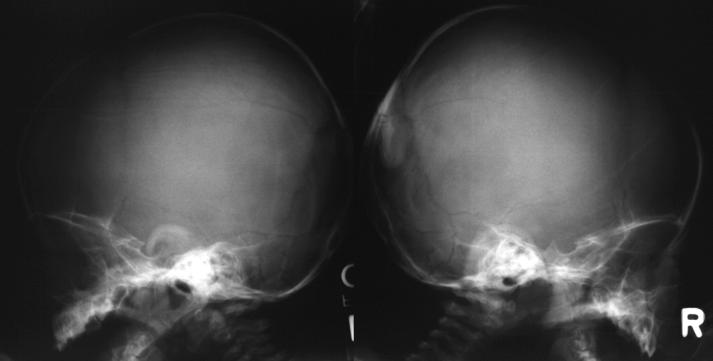

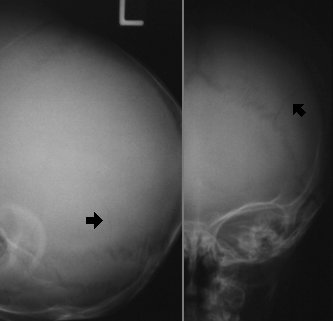

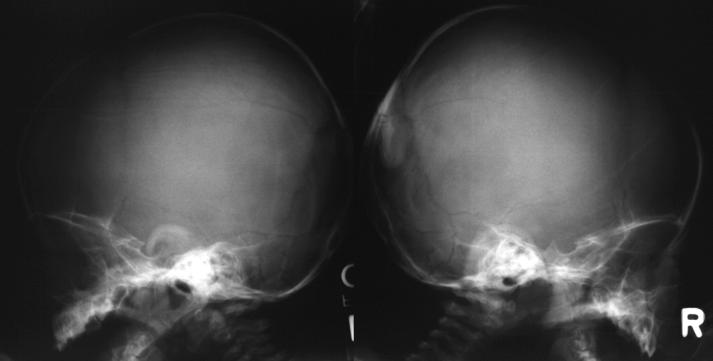

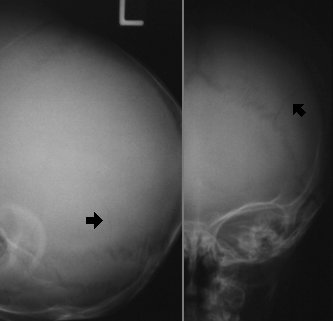

This 11-month old infant fell and struck his head on

a hard surface.

Case B Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior portion of the right

parietal bone extending across the lambdoidal suture

into the occipital bone.

This 11-month old infant fell and struck his head on

a hard surface.

Case B Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior portion of the right

parietal bone extending across the lambdoidal suture

into the occipital bone.

View Case C.

View Case C.

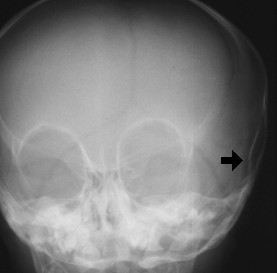

The history in this case is that this 2-month old fell

off a bed twice. It should be noted that this history is

highly suspicious. A 2-month old infant cannot move

about very much. While it may be possible for this

2-month old infant to have fallen off a bed once, it is

very unlikely that any parent would have allowed this to

occur twice on the same day.

Case C Interpretation:

Right parietal skull fracture.

The history in this case is that this 2-month old fell

off a bed twice. It should be noted that this history is

highly suspicious. A 2-month old infant cannot move

about very much. While it may be possible for this

2-month old infant to have fallen off a bed once, it is

very unlikely that any parent would have allowed this to

occur twice on the same day.

Case C Interpretation:

Right parietal skull fracture.

View Case D.

View Case D.

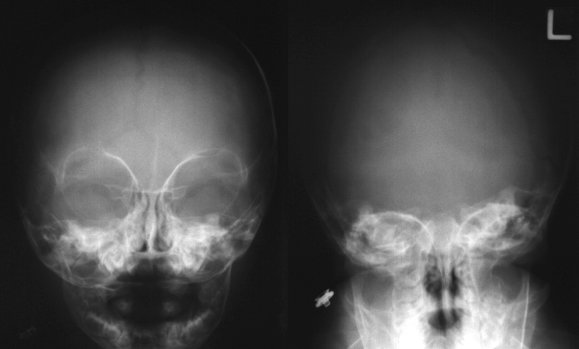

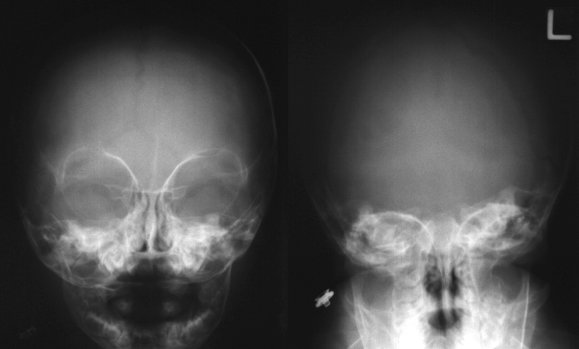

The mother of this 2-month infant fell onto a hard

surface while she was carrying her infant.

Case D Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the right occiput.

The mother of this 2-month infant fell onto a hard

surface while she was carrying her infant.

Case D Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the right occiput.

View Case E.

View Case E.

This 13-month old infant was noted to have a soft

swelling on his head two days following an episode of

head trauma following which, his behavior was normal.

Case E Interpretation:

Horizontal hairline fracture (very subtle) running

across the left temporal bone which extends posteriorly

to the level of the labdoidal suture.

This 13-month old infant was noted to have a soft

swelling on his head two days following an episode of

head trauma following which, his behavior was normal.

Case E Interpretation:

Horizontal hairline fracture (very subtle) running

across the left temporal bone which extends posteriorly

to the level of the labdoidal suture.

View Case F.

View Case F.

Case F Interpretation:

There is a depressed skull fracture over the

posterior right parietal bone. The hyperdense

(sclerotic) appearance of the skull abnormality indicates

the presence of a depressed skull fracture.

Case F Interpretation:

There is a depressed skull fracture over the

posterior right parietal bone. The hyperdense

(sclerotic) appearance of the skull abnormality indicates

the presence of a depressed skull fracture.

View Case G.

View Case G.

Case G Interpretation:

There is a 3 cm angled fracture in the right parietal

bone which communicates with the labdoidal suture.

Case G Interpretation:

There is a 3 cm angled fracture in the right parietal

bone which communicates with the labdoidal suture.

View Case H.

View Case H.

Case H Interpretation:

Linear skull fracture of the right parietal bone

extending from the labdoidal suture to the

parietomastoid suture.

Case H Interpretation:

Linear skull fracture of the right parietal bone

extending from the labdoidal suture to the

parietomastoid suture.

View Case I.

View Case I.

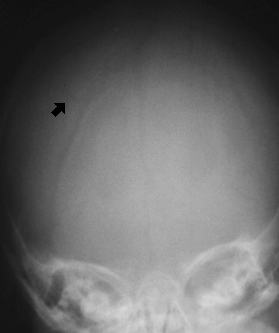

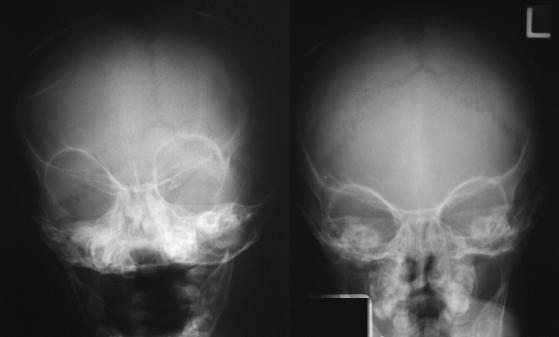

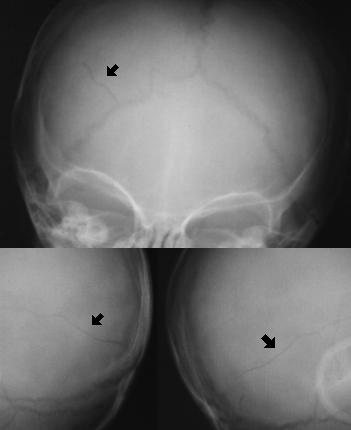

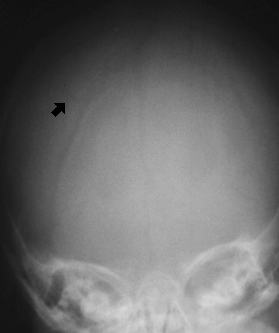

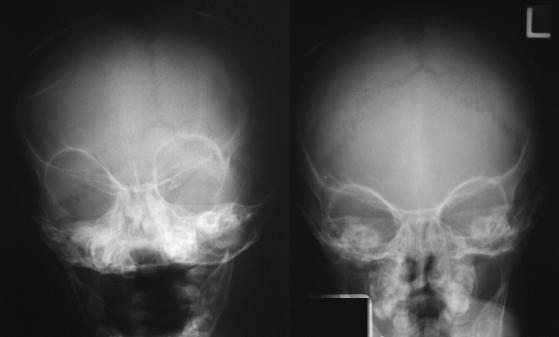

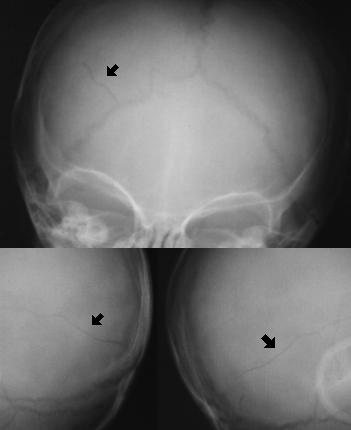

Case I Interpretation:

There is a short parietal skull fracture (very subtle)

near the vertex of the skull. It is difficult to lateralize on

the frontal views. It is probably on the left.

Case I Interpretation:

There is a short parietal skull fracture (very subtle)

near the vertex of the skull. It is difficult to lateralize on

the frontal views. It is probably on the left.

View Case J.

View Case J.

Case J Interpretation:

There is a fracture of the lower portion of the left

parietal bone.

Case J Interpretation:

There is a fracture of the lower portion of the left

parietal bone.

View Case K.

View Case K.

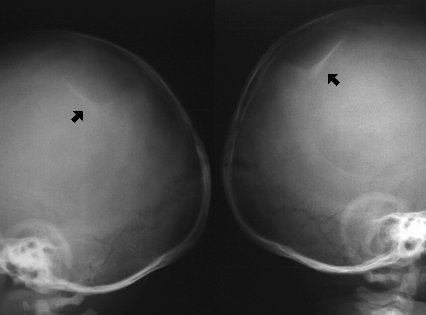

Case K Interpretation:

Long linear left parietal fracture extending from the

vertex to the labdoidal suture.

Case K Interpretation:

Long linear left parietal fracture extending from the

vertex to the labdoidal suture.

View Case L.

View Case L.

Case L Interpretation:

Linear fracture extending the length of the right

parietal bone.

Case L Interpretation:

Linear fracture extending the length of the right

parietal bone.

View Case M.

View Case M.

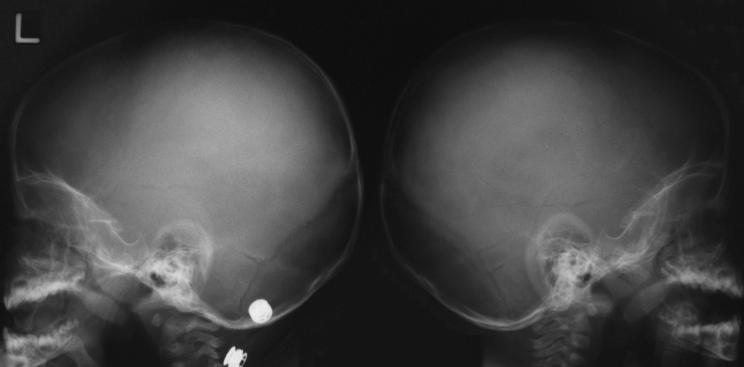

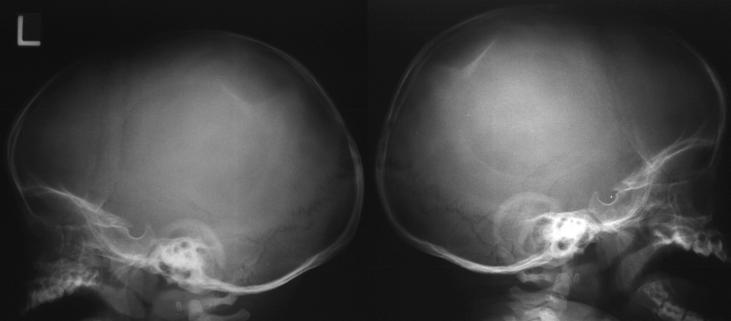

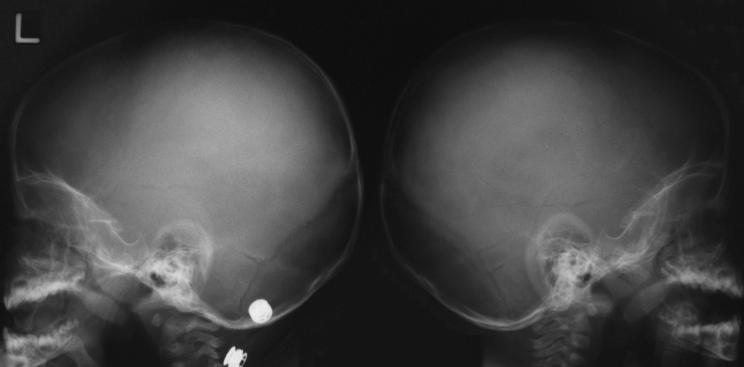

Case M Interpretation:

Biparietal skull fractures.

Case M Interpretation:

Biparietal skull fractures.

View Case N.

View Case N.

Case N Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior left parietal region.

Case N Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior left parietal region.

View Case O.

View Case O.

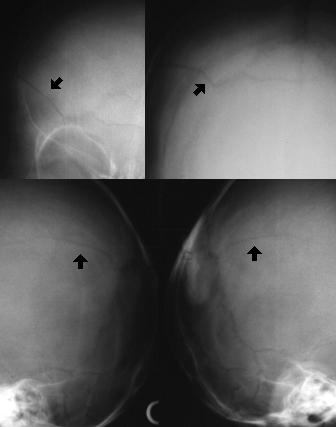

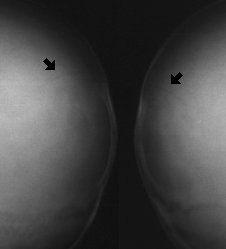

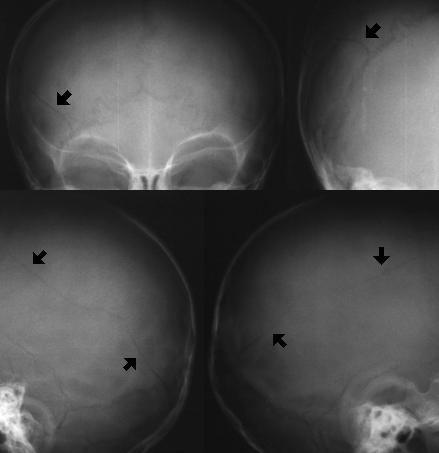

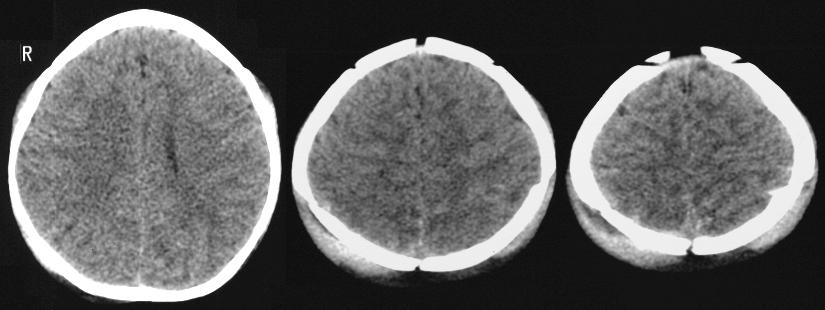

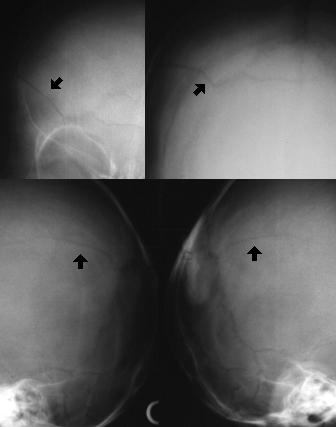

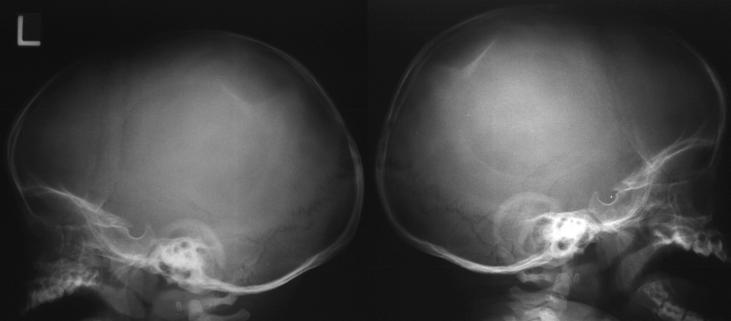

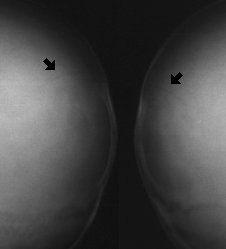

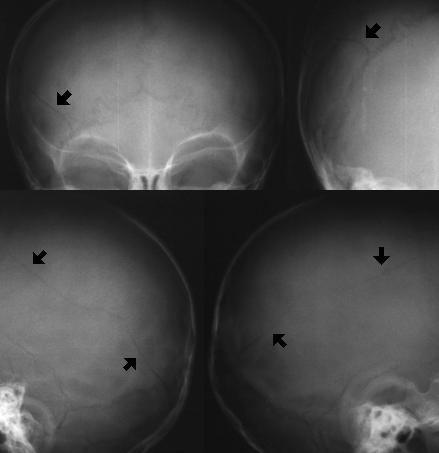

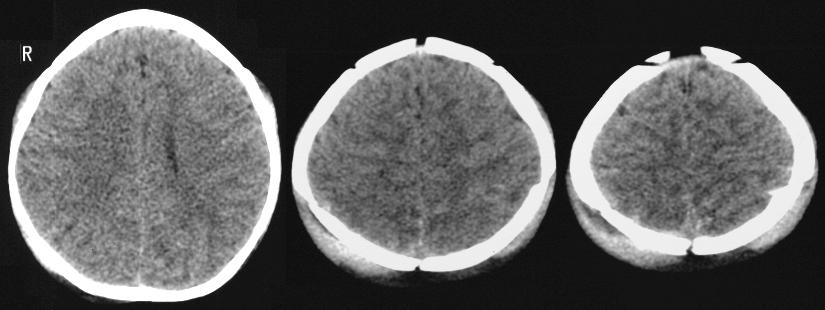

This is a CT scan image. While this case has

focused on plain skull radiographs, CT scans are often

ordered in cases of significant head trauma.

Radiologists will usually read CT scans. Identification

of the sutures versus fractures on CT can be difficult

without the knowledge of the usual appearance and

location of sutures.

Case O Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. Extensive soft tissue swelling

exterior to the skull is evident on this set of scans.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There are bilateral fractures of

the parietal region (arrows). The lambdoidal (L),

coronal (C), and sagittal (S) sutures are identified. Note

that the fracture is not seen in the lower cuts.

This is a CT scan image. While this case has

focused on plain skull radiographs, CT scans are often

ordered in cases of significant head trauma.

Radiologists will usually read CT scans. Identification

of the sutures versus fractures on CT can be difficult

without the knowledge of the usual appearance and

location of sutures.

Case O Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. Extensive soft tissue swelling

exterior to the skull is evident on this set of scans.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There are bilateral fractures of

the parietal region (arrows). The lambdoidal (L),

coronal (C), and sagittal (S) sutures are identified. Note

that the fracture is not seen in the lower cuts.

View Case P.

View Case P.

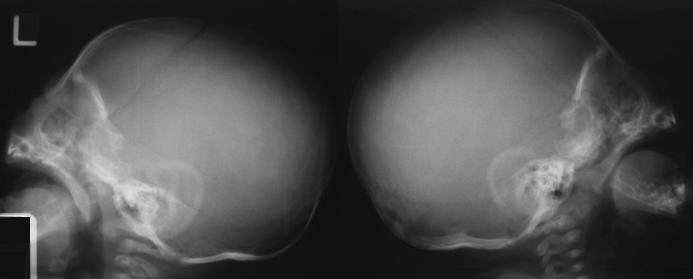

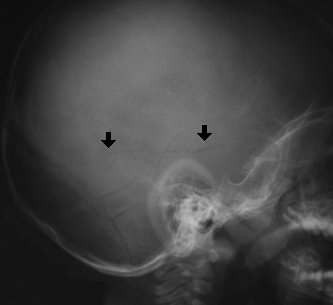

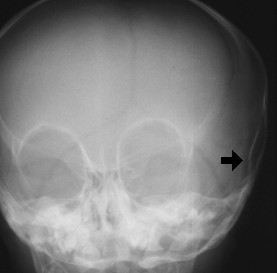

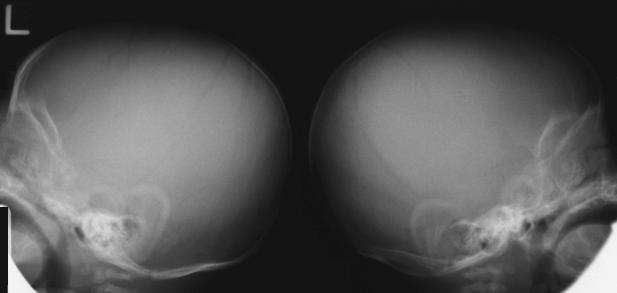

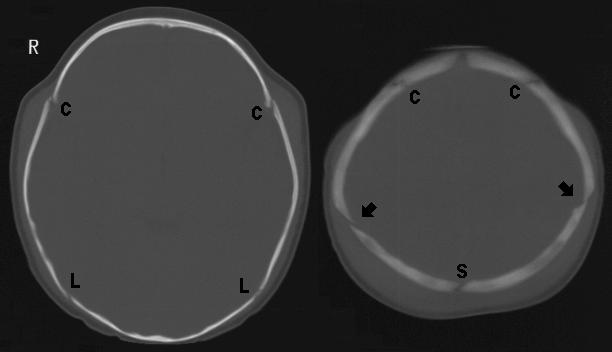

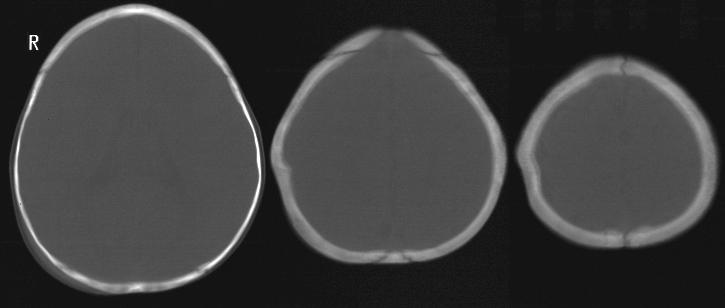

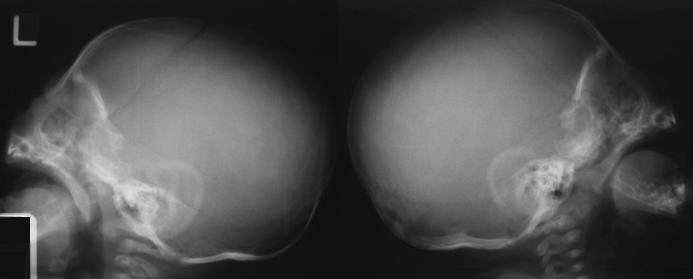

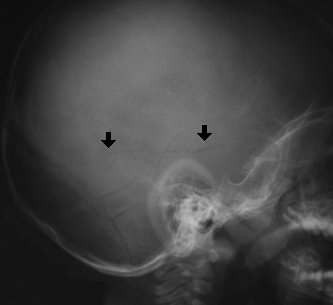

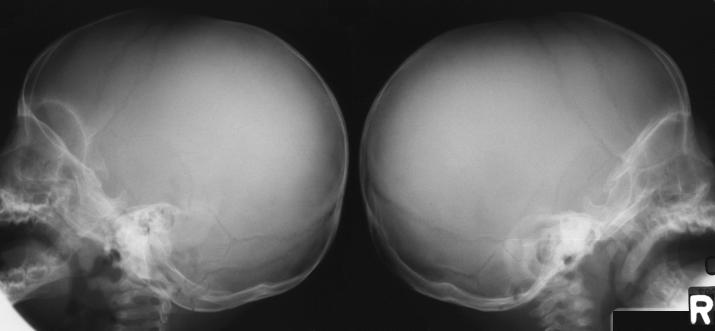

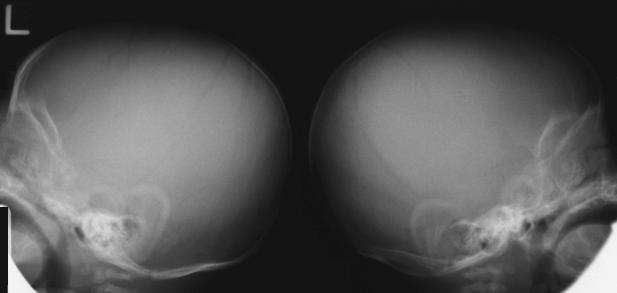

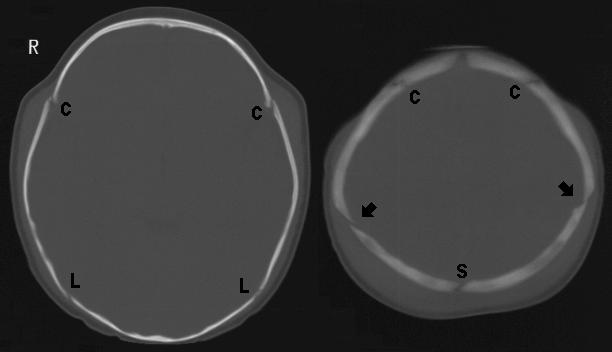

This is another CT scan case.

Case P Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. A skull depression is visible on

the right.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There is a depressed skull

fracture of the upper portion of the right parietal bone

(arrows). The lambdoidal (L) and coronal (C) sutures

are identified.

This is another CT scan case.

Case P Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. A skull depression is visible on

the right.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There is a depressed skull

fracture of the upper portion of the right parietal bone

(arrows). The lambdoidal (L) and coronal (C) sutures

are identified.

References:

Bruce DA. Head Trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, third

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1993, pp.

1105-1107.

The Head. In: Swischuk LE. Emergency Imaging

of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child, third edition.

Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1994, pp 577-592.

References:

Bruce DA. Head Trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, third

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1993, pp.

1105-1107.

The Head. In: Swischuk LE. Emergency Imaging

of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child, third edition.

Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1994, pp 577-592.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

Four standard views are often obtained. An AP

view, a Towne's view, and two lateral views. The

Towne's view is an AP view with the neck flexed

forward. Two lateral views can be more optimal than a

single lateral view to permit the film to focus on one

side at a time.

Locate the coronal, sagittal, and lambdoidal sutures

on these skull radiographs. In addition to these major

sutures, the anterior fontanelle is often visible. A suture

extends from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle

into the frontal bone. Two smaller sutures on each side

of the skull are present in the lower skull adjacent to the

mastoid; the parietomastoid suture and the

occipitomastoid suture.

View the locations of these sutures.

Four standard views are often obtained. An AP

view, a Towne's view, and two lateral views. The

Towne's view is an AP view with the neck flexed

forward. Two lateral views can be more optimal than a

single lateral view to permit the film to focus on one

side at a time.

Locate the coronal, sagittal, and lambdoidal sutures

on these skull radiographs. In addition to these major

sutures, the anterior fontanelle is often visible. A suture

extends from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle

into the frontal bone. Two smaller sutures on each side

of the skull are present in the lower skull adjacent to the

mastoid; the parietomastoid suture and the

occipitomastoid suture.

View the locations of these sutures.

C - Coronal

S - Sagittal

L - Lambdoidal

P - Parietomastoid (squamosal)

O - Occipitomastoid

The anterior fontanelle is outlined in the broken line.

Note that a suture extends anteriorly into the frontal

bone from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle.

Linear skull fractures are rarely associated with the

need for neurosurgical intervention. They will often

present to an acute care clinic or emergency

department several days after the injury with a

subgaleal hematoma (soft swelling on the side of the

head) as a chief complaint. These are benign and

should not be aspirated unless an infection is present.

Parietal skull fractures which cross the path of the

middle meningeal artery or other major vessels may be

associated with epidural or other types of intracranial

hemorrhage. In young children, the middle meningeal

artery does not groove into the bone as it does in adults

and thus, laceration of the middle meningeal artery is

less likely to occur (compared to adults) with a parietal

skull fracture. Roughly half of the epidural hematomas

in children occur in the absence of skull fractures.

Thus, plain film skull radiographs should not be used as

a routine screening measure to determine risk of

intracranial hemorrhage. CT scanning is more effective

at ruling out cerebral hemorrhages.

Neither CT nor plain film skull radiographs are highly

reliable in ruling out a basilar skull fracture. Such

fractures are difficult to see on CT scans and plain film

skull radiographs. This diagnosis is often made

clinically (nasal CSF leak, CSF otorrhea,

hemotympanum, Battle's sign, etc.) and then confirmed

on fine or angled CT cuts, or MRI.

Widely separated linear skull fractures (widely

diastatic) are associated with a higher risk of subdural

hematoma and an increased risk of developing

leptomeningeal cysts. The follow-up radiograph one

month later may show a "growing" fracture that results

from a meningeal laceration. This results in a bulging

leptomeningeal sac that causes erosion of the overlying

skull and an eventual skull defect if it is not repaired.

Depressed skull fractures may be evident on plain

radiographs, however, CT scanning is better able to

determine the extent of depression.

View the plain film skull radiographs to test your skill

in interpreting these radiographs.

View Case B.

C - Coronal

S - Sagittal

L - Lambdoidal

P - Parietomastoid (squamosal)

O - Occipitomastoid

The anterior fontanelle is outlined in the broken line.

Note that a suture extends anteriorly into the frontal

bone from the anterior tip of the anterior fontanelle.

Linear skull fractures are rarely associated with the

need for neurosurgical intervention. They will often

present to an acute care clinic or emergency

department several days after the injury with a

subgaleal hematoma (soft swelling on the side of the

head) as a chief complaint. These are benign and

should not be aspirated unless an infection is present.

Parietal skull fractures which cross the path of the

middle meningeal artery or other major vessels may be

associated with epidural or other types of intracranial

hemorrhage. In young children, the middle meningeal

artery does not groove into the bone as it does in adults

and thus, laceration of the middle meningeal artery is

less likely to occur (compared to adults) with a parietal

skull fracture. Roughly half of the epidural hematomas

in children occur in the absence of skull fractures.

Thus, plain film skull radiographs should not be used as

a routine screening measure to determine risk of

intracranial hemorrhage. CT scanning is more effective

at ruling out cerebral hemorrhages.

Neither CT nor plain film skull radiographs are highly

reliable in ruling out a basilar skull fracture. Such

fractures are difficult to see on CT scans and plain film

skull radiographs. This diagnosis is often made

clinically (nasal CSF leak, CSF otorrhea,

hemotympanum, Battle's sign, etc.) and then confirmed

on fine or angled CT cuts, or MRI.

Widely separated linear skull fractures (widely

diastatic) are associated with a higher risk of subdural

hematoma and an increased risk of developing

leptomeningeal cysts. The follow-up radiograph one

month later may show a "growing" fracture that results

from a meningeal laceration. This results in a bulging

leptomeningeal sac that causes erosion of the overlying

skull and an eventual skull defect if it is not repaired.

Depressed skull fractures may be evident on plain

radiographs, however, CT scanning is better able to

determine the extent of depression.

View the plain film skull radiographs to test your skill

in interpreting these radiographs.

View Case B.

This 11-month old infant fell and struck his head on

a hard surface.

Case B Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior portion of the right

parietal bone extending across the lambdoidal suture

into the occipital bone.

This 11-month old infant fell and struck his head on

a hard surface.

Case B Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior portion of the right

parietal bone extending across the lambdoidal suture

into the occipital bone.

View Case C.

View Case C.

The history in this case is that this 2-month old fell

off a bed twice. It should be noted that this history is

highly suspicious. A 2-month old infant cannot move

about very much. While it may be possible for this

2-month old infant to have fallen off a bed once, it is

very unlikely that any parent would have allowed this to

occur twice on the same day.

Case C Interpretation:

Right parietal skull fracture.

The history in this case is that this 2-month old fell

off a bed twice. It should be noted that this history is

highly suspicious. A 2-month old infant cannot move

about very much. While it may be possible for this

2-month old infant to have fallen off a bed once, it is

very unlikely that any parent would have allowed this to

occur twice on the same day.

Case C Interpretation:

Right parietal skull fracture.

View Case D.

View Case D.

The mother of this 2-month infant fell onto a hard

surface while she was carrying her infant.

Case D Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the right occiput.

The mother of this 2-month infant fell onto a hard

surface while she was carrying her infant.

Case D Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the right occiput.

View Case E.

View Case E.

This 13-month old infant was noted to have a soft

swelling on his head two days following an episode of

head trauma following which, his behavior was normal.

Case E Interpretation:

Horizontal hairline fracture (very subtle) running

across the left temporal bone which extends posteriorly

to the level of the labdoidal suture.

This 13-month old infant was noted to have a soft

swelling on his head two days following an episode of

head trauma following which, his behavior was normal.

Case E Interpretation:

Horizontal hairline fracture (very subtle) running

across the left temporal bone which extends posteriorly

to the level of the labdoidal suture.

View Case F.

View Case F.

Case F Interpretation:

There is a depressed skull fracture over the

posterior right parietal bone. The hyperdense

(sclerotic) appearance of the skull abnormality indicates

the presence of a depressed skull fracture.

Case F Interpretation:

There is a depressed skull fracture over the

posterior right parietal bone. The hyperdense

(sclerotic) appearance of the skull abnormality indicates

the presence of a depressed skull fracture.

View Case G.

View Case G.

Case G Interpretation:

There is a 3 cm angled fracture in the right parietal

bone which communicates with the labdoidal suture.

Case G Interpretation:

There is a 3 cm angled fracture in the right parietal

bone which communicates with the labdoidal suture.

View Case H.

View Case H.

Case H Interpretation:

Linear skull fracture of the right parietal bone

extending from the labdoidal suture to the

parietomastoid suture.

Case H Interpretation:

Linear skull fracture of the right parietal bone

extending from the labdoidal suture to the

parietomastoid suture.

View Case I.

View Case I.

Case I Interpretation:

There is a short parietal skull fracture (very subtle)

near the vertex of the skull. It is difficult to lateralize on

the frontal views. It is probably on the left.

Case I Interpretation:

There is a short parietal skull fracture (very subtle)

near the vertex of the skull. It is difficult to lateralize on

the frontal views. It is probably on the left.

View Case J.

View Case J.

Case J Interpretation:

There is a fracture of the lower portion of the left

parietal bone.

Case J Interpretation:

There is a fracture of the lower portion of the left

parietal bone.

View Case K.

View Case K.

Case K Interpretation:

Long linear left parietal fracture extending from the

vertex to the labdoidal suture.

Case K Interpretation:

Long linear left parietal fracture extending from the

vertex to the labdoidal suture.

View Case L.

View Case L.

Case L Interpretation:

Linear fracture extending the length of the right

parietal bone.

Case L Interpretation:

Linear fracture extending the length of the right

parietal bone.

View Case M.

View Case M.

Case M Interpretation:

Biparietal skull fractures.

Case M Interpretation:

Biparietal skull fractures.

View Case N.

View Case N.

Case N Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior left parietal region.

Case N Interpretation:

Linear fracture of the posterior left parietal region.

View Case O.

View Case O.

This is a CT scan image. While this case has

focused on plain skull radiographs, CT scans are often

ordered in cases of significant head trauma.

Radiologists will usually read CT scans. Identification

of the sutures versus fractures on CT can be difficult

without the knowledge of the usual appearance and

location of sutures.

Case O Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. Extensive soft tissue swelling

exterior to the skull is evident on this set of scans.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There are bilateral fractures of

the parietal region (arrows). The lambdoidal (L),

coronal (C), and sagittal (S) sutures are identified. Note

that the fracture is not seen in the lower cuts.

This is a CT scan image. While this case has

focused on plain skull radiographs, CT scans are often

ordered in cases of significant head trauma.

Radiologists will usually read CT scans. Identification

of the sutures versus fractures on CT can be difficult

without the knowledge of the usual appearance and

location of sutures.

Case O Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. Extensive soft tissue swelling

exterior to the skull is evident on this set of scans.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There are bilateral fractures of

the parietal region (arrows). The lambdoidal (L),

coronal (C), and sagittal (S) sutures are identified. Note

that the fracture is not seen in the lower cuts.

View Case P.

View Case P.

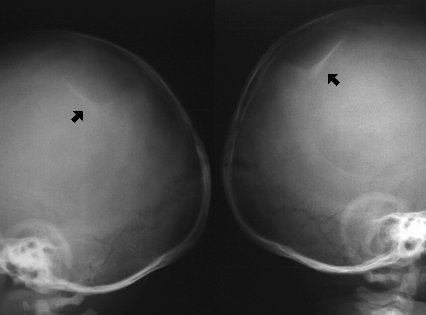

This is another CT scan case.

Case P Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. A skull depression is visible on

the right.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There is a depressed skull

fracture of the upper portion of the right parietal bone

(arrows). The lambdoidal (L) and coronal (C) sutures

are identified.

This is another CT scan case.

Case P Interpretation:

The top set of scans focuses on the brain which

appears to be normal. A skull depression is visible on

the right.

The lower set of scans is contrasted to view the

bones (bone windows). There is a depressed skull

fracture of the upper portion of the right parietal bone

(arrows). The lambdoidal (L) and coronal (C) sutures

are identified.

References:

Bruce DA. Head Trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, third

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1993, pp.

1105-1107.

The Head. In: Swischuk LE. Emergency Imaging

of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child, third edition.

Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1994, pp 577-592.

References:

Bruce DA. Head Trauma. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig

S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, third

edition. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1993, pp.

1105-1107.

The Head. In: Swischuk LE. Emergency Imaging

of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child, third edition.

Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1994, pp 577-592.