Acute Chest Pain in a Tall Slender Teenager

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 3, Case 13

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

A 15-year old male presents to the E.D. with a one

hour history of pain in his chest and back occurring

after lifting his mother. He describes the pain as

knife-like and non radiating. His pain worsens with

deep inspiration. His pain is currently less severe than

at onset. He has a past history of chest pain episodes,

usually at night while sleeping in bed.

Exam VS T37 (tympanic), P76, R24, BP 131/65.

Oxygen saturation 100% in room air. He is alert and

active in no distress. He is tall and thin. Heart regular,

no murmurs. Lungs clear, but diminished breath

sounds bilaterally. Abdomen benign. Peripheral pulses

are full. Color and perfusion are good. Hands

significant for long thin fingers (arachnodactyly).

A chest radiograph is ordered.

View CXR.

This CXR shows a long thorax with hyperexpanded

lungs. The aortic shadow is not obviously widened.

The cardiac silhouette is not enlarged. There is no

obvious pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or

subcutaneous emphysema.

Aortic dissection is suspected because of his

Marfanoid appearance. A CT scan of the chest and

aorta is ordered.

View CT scan.

This CXR shows a long thorax with hyperexpanded

lungs. The aortic shadow is not obviously widened.

The cardiac silhouette is not enlarged. There is no

obvious pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or

subcutaneous emphysema.

Aortic dissection is suspected because of his

Marfanoid appearance. A CT scan of the chest and

aorta is ordered.

View CT scan.

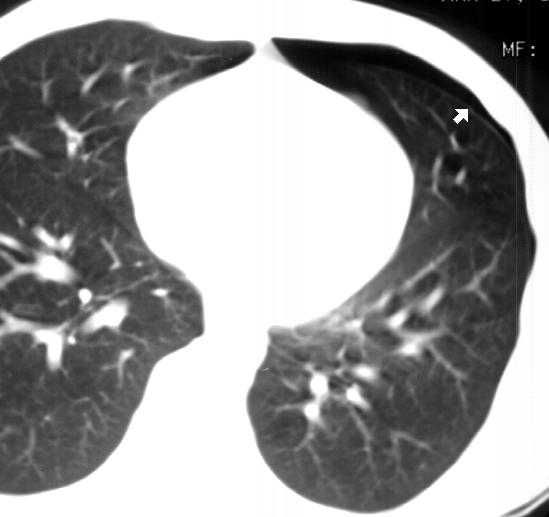

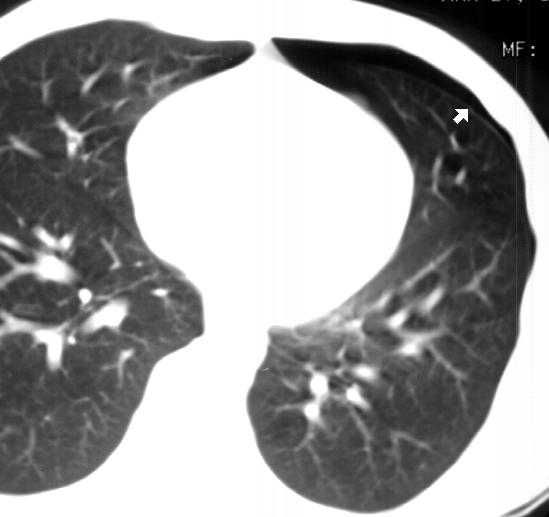

The CT scan demonstrates a small left-sided

pneumothorax. The arrows point to the visceral pleura

of the lung. An air space is evident within the pleural

space. The aorta is normal.

Upon closer inspection of subsequent CXR's, the

pneumothorax is visible as a thin rim of air over the

apex of the left lung. It is more obvious on erect and

expiratory views. Pneumothoraces may be difficult to

see on a supine or a partially supine film. The patient

should be upright or in the lateral decubitus position to

see it best.

View close-up of left apex and expiratory view.

The CT scan demonstrates a small left-sided

pneumothorax. The arrows point to the visceral pleura

of the lung. An air space is evident within the pleural

space. The aorta is normal.

Upon closer inspection of subsequent CXR's, the

pneumothorax is visible as a thin rim of air over the

apex of the left lung. It is more obvious on erect and

expiratory views. Pneumothoraces may be difficult to

see on a supine or a partially supine film. The patient

should be upright or in the lateral decubitus position to

see it best.

View close-up of left apex and expiratory view.

After reviewing the previous case of aortic

dissection, chest pain in a tall slender patient

suggesting Marfan's Syndrome, is highly suggestive of

another aortic dissection. Marfan's Syndrome is a

connective tissue disorder prone to aortic dissection.

Patients with Marfan's Syndrome classically have a

body stature similar to that of Abraham Lincoln.

Although such tall slender individuals with chest pain

raise the possibility of aortic dissection, such individuals

are also at a higher risk of a spontaneous

pneumothorax. Other activities associated with an

increased risk of air leaks include coughing, valsalva

maneuvers (eg., musical instrument playing and

carrying one's mother), substance abuse, positive

pressure devices, etc. Patients with chronic lung

disease such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic

fibrosis, bronchiectasis, metastatic disease, etc., are at

greater risk for a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Patients with a spontaneous pneumothorax may

present with chest pain or symptoms of respiratory

difficulty. The chest pain may be similar to that of chest

wall pain in that the pain is usually worse when taking in

a deep breath. Crepitance may be palpable if air is

dissecting into the soft tissues of the neck or the chest

wall. Diminished breath sounds may be noticeable if

the pneumothorax is large enough. Small

pneumothoraces may not be detectable by auscultation.

An immediate chest tube is indicated only if the

patient is in severe distress. Otherwise, it may be best

to obtain a chest radiograph to establish a diagnosis

before performing an invasive procedure. This

pneumothorax was difficult to see on this recumbent

CXR view. If a pneumothorax is still suspected, an

expiratory erect view would accentuate the radiographic

findings, making it easier to identify a small

pneumothorax. As demonstrated in this case, CT scan

is very sensitive at identifying a pneumothorax, but it is

usually not necessary since pneumothoraces can

usually be identified on plain radiographs.

If the pneumothorax is small and the patient is doing

well, it is usually not necessary to evacuate it with a

thoracentesis or a tube thoracostomy. If no

deterioration is noted during an observation period in

the emergency department (that meets with the comfort

level of the physician and family), it may not be

necessary to hospitalize the patient (especially with

teenagers) with a small pneumothorax, if follow-up is

reliable and the family lives near a medical facility.

Elective consultation with a surgeon may be beneficial if

a tube thoracostomy is anticipated.

References

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1348-1349.

After reviewing the previous case of aortic

dissection, chest pain in a tall slender patient

suggesting Marfan's Syndrome, is highly suggestive of

another aortic dissection. Marfan's Syndrome is a

connective tissue disorder prone to aortic dissection.

Patients with Marfan's Syndrome classically have a

body stature similar to that of Abraham Lincoln.

Although such tall slender individuals with chest pain

raise the possibility of aortic dissection, such individuals

are also at a higher risk of a spontaneous

pneumothorax. Other activities associated with an

increased risk of air leaks include coughing, valsalva

maneuvers (eg., musical instrument playing and

carrying one's mother), substance abuse, positive

pressure devices, etc. Patients with chronic lung

disease such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic

fibrosis, bronchiectasis, metastatic disease, etc., are at

greater risk for a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Patients with a spontaneous pneumothorax may

present with chest pain or symptoms of respiratory

difficulty. The chest pain may be similar to that of chest

wall pain in that the pain is usually worse when taking in

a deep breath. Crepitance may be palpable if air is

dissecting into the soft tissues of the neck or the chest

wall. Diminished breath sounds may be noticeable if

the pneumothorax is large enough. Small

pneumothoraces may not be detectable by auscultation.

An immediate chest tube is indicated only if the

patient is in severe distress. Otherwise, it may be best

to obtain a chest radiograph to establish a diagnosis

before performing an invasive procedure. This

pneumothorax was difficult to see on this recumbent

CXR view. If a pneumothorax is still suspected, an

expiratory erect view would accentuate the radiographic

findings, making it easier to identify a small

pneumothorax. As demonstrated in this case, CT scan

is very sensitive at identifying a pneumothorax, but it is

usually not necessary since pneumothoraces can

usually be identified on plain radiographs.

If the pneumothorax is small and the patient is doing

well, it is usually not necessary to evacuate it with a

thoracentesis or a tube thoracostomy. If no

deterioration is noted during an observation period in

the emergency department (that meets with the comfort

level of the physician and family), it may not be

necessary to hospitalize the patient (especially with

teenagers) with a small pneumothorax, if follow-up is

reliable and the family lives near a medical facility.

Elective consultation with a surgeon may be beneficial if

a tube thoracostomy is anticipated.

References

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1348-1349.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

This CXR shows a long thorax with hyperexpanded

lungs. The aortic shadow is not obviously widened.

The cardiac silhouette is not enlarged. There is no

obvious pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or

subcutaneous emphysema.

Aortic dissection is suspected because of his

Marfanoid appearance. A CT scan of the chest and

aorta is ordered.

View CT scan.

This CXR shows a long thorax with hyperexpanded

lungs. The aortic shadow is not obviously widened.

The cardiac silhouette is not enlarged. There is no

obvious pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or

subcutaneous emphysema.

Aortic dissection is suspected because of his

Marfanoid appearance. A CT scan of the chest and

aorta is ordered.

View CT scan.

The CT scan demonstrates a small left-sided

pneumothorax. The arrows point to the visceral pleura

of the lung. An air space is evident within the pleural

space. The aorta is normal.

Upon closer inspection of subsequent CXR's, the

pneumothorax is visible as a thin rim of air over the

apex of the left lung. It is more obvious on erect and

expiratory views. Pneumothoraces may be difficult to

see on a supine or a partially supine film. The patient

should be upright or in the lateral decubitus position to

see it best.

View close-up of left apex and expiratory view.

The CT scan demonstrates a small left-sided

pneumothorax. The arrows point to the visceral pleura

of the lung. An air space is evident within the pleural

space. The aorta is normal.

Upon closer inspection of subsequent CXR's, the

pneumothorax is visible as a thin rim of air over the

apex of the left lung. It is more obvious on erect and

expiratory views. Pneumothoraces may be difficult to

see on a supine or a partially supine film. The patient

should be upright or in the lateral decubitus position to

see it best.

View close-up of left apex and expiratory view.

After reviewing the previous case of aortic

dissection, chest pain in a tall slender patient

suggesting Marfan's Syndrome, is highly suggestive of

another aortic dissection. Marfan's Syndrome is a

connective tissue disorder prone to aortic dissection.

Patients with Marfan's Syndrome classically have a

body stature similar to that of Abraham Lincoln.

Although such tall slender individuals with chest pain

raise the possibility of aortic dissection, such individuals

are also at a higher risk of a spontaneous

pneumothorax. Other activities associated with an

increased risk of air leaks include coughing, valsalva

maneuvers (eg., musical instrument playing and

carrying one's mother), substance abuse, positive

pressure devices, etc. Patients with chronic lung

disease such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic

fibrosis, bronchiectasis, metastatic disease, etc., are at

greater risk for a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Patients with a spontaneous pneumothorax may

present with chest pain or symptoms of respiratory

difficulty. The chest pain may be similar to that of chest

wall pain in that the pain is usually worse when taking in

a deep breath. Crepitance may be palpable if air is

dissecting into the soft tissues of the neck or the chest

wall. Diminished breath sounds may be noticeable if

the pneumothorax is large enough. Small

pneumothoraces may not be detectable by auscultation.

An immediate chest tube is indicated only if the

patient is in severe distress. Otherwise, it may be best

to obtain a chest radiograph to establish a diagnosis

before performing an invasive procedure. This

pneumothorax was difficult to see on this recumbent

CXR view. If a pneumothorax is still suspected, an

expiratory erect view would accentuate the radiographic

findings, making it easier to identify a small

pneumothorax. As demonstrated in this case, CT scan

is very sensitive at identifying a pneumothorax, but it is

usually not necessary since pneumothoraces can

usually be identified on plain radiographs.

If the pneumothorax is small and the patient is doing

well, it is usually not necessary to evacuate it with a

thoracentesis or a tube thoracostomy. If no

deterioration is noted during an observation period in

the emergency department (that meets with the comfort

level of the physician and family), it may not be

necessary to hospitalize the patient (especially with

teenagers) with a small pneumothorax, if follow-up is

reliable and the family lives near a medical facility.

Elective consultation with a surgeon may be beneficial if

a tube thoracostomy is anticipated.

References

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1348-1349.

After reviewing the previous case of aortic

dissection, chest pain in a tall slender patient

suggesting Marfan's Syndrome, is highly suggestive of

another aortic dissection. Marfan's Syndrome is a

connective tissue disorder prone to aortic dissection.

Patients with Marfan's Syndrome classically have a

body stature similar to that of Abraham Lincoln.

Although such tall slender individuals with chest pain

raise the possibility of aortic dissection, such individuals

are also at a higher risk of a spontaneous

pneumothorax. Other activities associated with an

increased risk of air leaks include coughing, valsalva

maneuvers (eg., musical instrument playing and

carrying one's mother), substance abuse, positive

pressure devices, etc. Patients with chronic lung

disease such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic

fibrosis, bronchiectasis, metastatic disease, etc., are at

greater risk for a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Patients with a spontaneous pneumothorax may

present with chest pain or symptoms of respiratory

difficulty. The chest pain may be similar to that of chest

wall pain in that the pain is usually worse when taking in

a deep breath. Crepitance may be palpable if air is

dissecting into the soft tissues of the neck or the chest

wall. Diminished breath sounds may be noticeable if

the pneumothorax is large enough. Small

pneumothoraces may not be detectable by auscultation.

An immediate chest tube is indicated only if the

patient is in severe distress. Otherwise, it may be best

to obtain a chest radiograph to establish a diagnosis

before performing an invasive procedure. This

pneumothorax was difficult to see on this recumbent

CXR view. If a pneumothorax is still suspected, an

expiratory erect view would accentuate the radiographic

findings, making it easier to identify a small

pneumothorax. As demonstrated in this case, CT scan

is very sensitive at identifying a pneumothorax, but it is

usually not necessary since pneumothoraces can

usually be identified on plain radiographs.

If the pneumothorax is small and the patient is doing

well, it is usually not necessary to evacuate it with a

thoracentesis or a tube thoracostomy. If no

deterioration is noted during an observation period in

the emergency department (that meets with the comfort

level of the physician and family), it may not be

necessary to hospitalize the patient (especially with

teenagers) with a small pneumothorax, if follow-up is

reliable and the family lives near a medical facility.

Elective consultation with a surgeon may be beneficial if

a tube thoracostomy is anticipated.

References

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, MD, Williams and

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1348-1349.