A Hand Contusion

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 1, Case 14

Alson S. Inaba, MD

Rodney B. Boychuk, MD

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

A 17 year old male presents to the ED with right

wrist and hand pain two hours after falling on his

out-stretched (extended) right hand. The patient was

jogging along the sidewalk when he lost his balance,

tripped on the curb and broke his fall by landing on his

out-stretched right hand. There was no loss of

consciousness and the only area of pain was his right

wrist.

Exam: Except for some very superficial palmar

abrasions, there were no other visible signs of external

trauma over the entire right upper extremity from the

clavicle to the tips of the fingers. The shoulder and

elbow both demonstrated full range of motion without

any pain. His fingers were all pink with intact

neurovascular integrity. Upon closer examination of the

wrist, the patient complained of point tenderness in the

floor of the anatomic snuff box. This point tenderness

was exacerbated with wrist flexion, extension and radial

deviation. Because of point tenderness in this area,

radiographs were obtained to rule out a fracture.

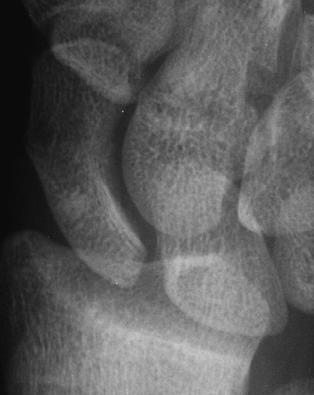

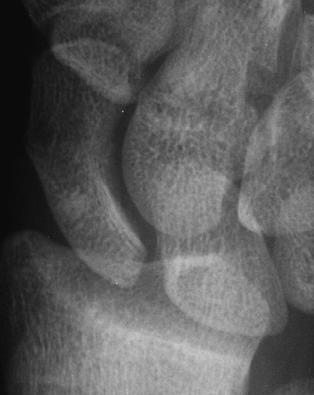

View wrist radiographs: AP view

View wrist radiographs: Oblique view

View wrist radiographs: Oblique view

The lateral view of the wrist was not contributory so

it is not included here. A scaphoid view was also taken

because of the area of tenderness over the scaphoid.

View scaphoid radiograph.

The lateral view of the wrist was not contributory so

it is not included here. A scaphoid view was also taken

because of the area of tenderness over the scaphoid.

View scaphoid radiograph.

Questions:

1) What is the significance of point tenderness in

the area of the scaphoid (navicular) bone?

2) How would you interpret the radiographs shown

above?

3) What are the complications of this type of injury?

4) How should these types of injuries be managed

in the ED and when should you consult an orthopedic

surgeon?

This set of radiographs were initially read by the

emergency physician as normal. However, a fracture

was still suspected and the patient was placed in a

thumb spica splint and given orthopedic referral

arrangements. A radiologist then read the radiographs

as showing a tiny fracture of the scaphoid. On the

enlarged views of the scaphoid, there is a slight

irregularity of the cortex on the lateral side. You may

have to adjust the brightness and contrast on your

monitor to appreciate this. A second radiologist

disagreed and insisted that these radiographs were

normal.

Teaching Points:

a) Point tenderness in the "anatomic snuff box"

region should always alert one to the possibility of a

scaphoid (navicular) fracture. The scaphoid bone is the

most commonly fractured carpal bone. These types of

fractures are most commonly seen in patients between

15 and 35 years of age as a result of a forceful

hyperextension type injury to the wrist.

View another example.

Questions:

1) What is the significance of point tenderness in

the area of the scaphoid (navicular) bone?

2) How would you interpret the radiographs shown

above?

3) What are the complications of this type of injury?

4) How should these types of injuries be managed

in the ED and when should you consult an orthopedic

surgeon?

This set of radiographs were initially read by the

emergency physician as normal. However, a fracture

was still suspected and the patient was placed in a

thumb spica splint and given orthopedic referral

arrangements. A radiologist then read the radiographs

as showing a tiny fracture of the scaphoid. On the

enlarged views of the scaphoid, there is a slight

irregularity of the cortex on the lateral side. You may

have to adjust the brightness and contrast on your

monitor to appreciate this. A second radiologist

disagreed and insisted that these radiographs were

normal.

Teaching Points:

a) Point tenderness in the "anatomic snuff box"

region should always alert one to the possibility of a

scaphoid (navicular) fracture. The scaphoid bone is the

most commonly fractured carpal bone. These types of

fractures are most commonly seen in patients between

15 and 35 years of age as a result of a forceful

hyperextension type injury to the wrist.

View another example.

This patient complained of distal forearm pain. The

scaphoid region was not specifically examined. This

pitfall must be avoided. A forearm film which included

the wrist was obtained. A distal radius fracture and an

ulnar styloid fracture were noted. At the very top of the

film, where it ends, a fracture through the scaphoid was

noted. Patients may not complain of pain exactly over

the fracture site, especially when there are fractures

elsewhere. However, examination for the location(s) of

point tenderness will usually improve the clinician's

ability to locate the site of injury.

View another example.

This patient complained of distal forearm pain. The

scaphoid region was not specifically examined. This

pitfall must be avoided. A forearm film which included

the wrist was obtained. A distal radius fracture and an

ulnar styloid fracture were noted. At the very top of the

film, where it ends, a fracture through the scaphoid was

noted. Patients may not complain of pain exactly over

the fracture site, especially when there are fractures

elsewhere. However, examination for the location(s) of

point tenderness will usually improve the clinician's

ability to locate the site of injury.

View another example.

This radiograph shows another scaphoid fracture.

However even in the absence of such a radiographically

evident fracture, point tenderness over the scaphoid

warrants the same treatment.

View the anatomic snuff box.

This radiograph shows another scaphoid fracture.

However even in the absence of such a radiographically

evident fracture, point tenderness over the scaphoid

warrants the same treatment.

View the anatomic snuff box.

The arrow points to the floor of the anatomic snuff

box. The scaphoid bone forms the floor of the anatomic

snuff box. Tenderness in the area should raise the

suspicion of a scaphoid fracture.

b) The blood supply to the scaphoid penetrates

the cortex at both the distal aspect (on the dorsal

aspect near the scaphoid turbercle) and the waist

(middle third of the scaphoid). Because of this tenuous

blood supply, there is no direct blood supply to the

proximal third of the scaphoid. Therefore, scaphoid

fractures (even if properly diagnosed and treated) have

a tendency for dreaded complications, such as

avascular necrosis of the proximal third and non-union.

In general, the more proximal the fracture, the greater

the likelihood of avascular necrosis.

c) Although adults are more likely to present with

fractures involving the middle third or proximal aspect of

the scaphoid, children have a higher incidence of

fractures involving the distal third of the scaphoid.

d) If one is clinically suspicious of a scaphoid

fracture, always be sure to obtain isolated scaphoid

views in addition to the standard AP, lateral and oblique

views of the wrist. Even if there is no obvious

radiographic evidence of a scaphoid fracture, all

patients with point tenderness over the anatomic snuff

box region should be properly immobilized in the ED

and referred to an orthopedist for further evaluation and

management.

e) Proper immobilization of a scaphoid fracture

should prevent wrist flexion/extension, radial wrist

deviation and any movement of the thumb metacarpal.

Therefore a simple volar wrist splint would NOT be

considered proper immobilization for a scaphoid

fracture. A more adequate immobilization technique

would be to apply a thumb spica/radial gutter splint

(which could also be combined with a volar wrist splint).

View thumb spica/radial gutter splint.

The arrow points to the floor of the anatomic snuff

box. The scaphoid bone forms the floor of the anatomic

snuff box. Tenderness in the area should raise the

suspicion of a scaphoid fracture.

b) The blood supply to the scaphoid penetrates

the cortex at both the distal aspect (on the dorsal

aspect near the scaphoid turbercle) and the waist

(middle third of the scaphoid). Because of this tenuous

blood supply, there is no direct blood supply to the

proximal third of the scaphoid. Therefore, scaphoid

fractures (even if properly diagnosed and treated) have

a tendency for dreaded complications, such as

avascular necrosis of the proximal third and non-union.

In general, the more proximal the fracture, the greater

the likelihood of avascular necrosis.

c) Although adults are more likely to present with

fractures involving the middle third or proximal aspect of

the scaphoid, children have a higher incidence of

fractures involving the distal third of the scaphoid.

d) If one is clinically suspicious of a scaphoid

fracture, always be sure to obtain isolated scaphoid

views in addition to the standard AP, lateral and oblique

views of the wrist. Even if there is no obvious

radiographic evidence of a scaphoid fracture, all

patients with point tenderness over the anatomic snuff

box region should be properly immobilized in the ED

and referred to an orthopedist for further evaluation and

management.

e) Proper immobilization of a scaphoid fracture

should prevent wrist flexion/extension, radial wrist

deviation and any movement of the thumb metacarpal.

Therefore a simple volar wrist splint would NOT be

considered proper immobilization for a scaphoid

fracture. A more adequate immobilization technique

would be to apply a thumb spica/radial gutter splint

(which could also be combined with a volar wrist splint).

View thumb spica/radial gutter splint.

Only the radial gutter and thumb immobilizing

portion of the splint is shown here without the overlying

elastic wrap. The thumb is immobilized to prevent wrist

ab/ad-duction and first metacarpal movement. A volar

splint can be added to this.

f) Definitive treatment by an orthopedic surgeon

usually involves a thumb spica cast for 6-12 weeks.

References

1. Simon RR, Koenigsknecht SJ: Emergency

Orthopedics: The Extremities (second edition).

Appleton & Lange, pp. 81-84, 1987.

2. Letts RM: Management of Pediatric Fractures.

Churchill Livingston, pp. 389-396, 1994.

3. Etzwiler LS. Hand and Wrist Injuries. In:

Barkin R (ed). Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts

and Clinical Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book,

1992, p. 332.

Only the radial gutter and thumb immobilizing

portion of the splint is shown here without the overlying

elastic wrap. The thumb is immobilized to prevent wrist

ab/ad-duction and first metacarpal movement. A volar

splint can be added to this.

f) Definitive treatment by an orthopedic surgeon

usually involves a thumb spica cast for 6-12 weeks.

References

1. Simon RR, Koenigsknecht SJ: Emergency

Orthopedics: The Extremities (second edition).

Appleton & Lange, pp. 81-84, 1987.

2. Letts RM: Management of Pediatric Fractures.

Churchill Livingston, pp. 389-396, 1994.

3. Etzwiler LS. Hand and Wrist Injuries. In:

Barkin R (ed). Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts

and Clinical Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book,

1992, p. 332.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

View wrist radiographs: Oblique view

View wrist radiographs: Oblique view

The lateral view of the wrist was not contributory so

it is not included here. A scaphoid view was also taken

because of the area of tenderness over the scaphoid.

View scaphoid radiograph.

The lateral view of the wrist was not contributory so

it is not included here. A scaphoid view was also taken

because of the area of tenderness over the scaphoid.

View scaphoid radiograph.

Questions:

1) What is the significance of point tenderness in

the area of the scaphoid (navicular) bone?

2) How would you interpret the radiographs shown

above?

3) What are the complications of this type of injury?

4) How should these types of injuries be managed

in the ED and when should you consult an orthopedic

surgeon?

This set of radiographs were initially read by the

emergency physician as normal. However, a fracture

was still suspected and the patient was placed in a

thumb spica splint and given orthopedic referral

arrangements. A radiologist then read the radiographs

as showing a tiny fracture of the scaphoid. On the

enlarged views of the scaphoid, there is a slight

irregularity of the cortex on the lateral side. You may

have to adjust the brightness and contrast on your

monitor to appreciate this. A second radiologist

disagreed and insisted that these radiographs were

normal.

Teaching Points:

a) Point tenderness in the "anatomic snuff box"

region should always alert one to the possibility of a

scaphoid (navicular) fracture. The scaphoid bone is the

most commonly fractured carpal bone. These types of

fractures are most commonly seen in patients between

15 and 35 years of age as a result of a forceful

hyperextension type injury to the wrist.

View another example.

Questions:

1) What is the significance of point tenderness in

the area of the scaphoid (navicular) bone?

2) How would you interpret the radiographs shown

above?

3) What are the complications of this type of injury?

4) How should these types of injuries be managed

in the ED and when should you consult an orthopedic

surgeon?

This set of radiographs were initially read by the

emergency physician as normal. However, a fracture

was still suspected and the patient was placed in a

thumb spica splint and given orthopedic referral

arrangements. A radiologist then read the radiographs

as showing a tiny fracture of the scaphoid. On the

enlarged views of the scaphoid, there is a slight

irregularity of the cortex on the lateral side. You may

have to adjust the brightness and contrast on your

monitor to appreciate this. A second radiologist

disagreed and insisted that these radiographs were

normal.

Teaching Points:

a) Point tenderness in the "anatomic snuff box"

region should always alert one to the possibility of a

scaphoid (navicular) fracture. The scaphoid bone is the

most commonly fractured carpal bone. These types of

fractures are most commonly seen in patients between

15 and 35 years of age as a result of a forceful

hyperextension type injury to the wrist.

View another example.

This patient complained of distal forearm pain. The

scaphoid region was not specifically examined. This

pitfall must be avoided. A forearm film which included

the wrist was obtained. A distal radius fracture and an

ulnar styloid fracture were noted. At the very top of the

film, where it ends, a fracture through the scaphoid was

noted. Patients may not complain of pain exactly over

the fracture site, especially when there are fractures

elsewhere. However, examination for the location(s) of

point tenderness will usually improve the clinician's

ability to locate the site of injury.

View another example.

This patient complained of distal forearm pain. The

scaphoid region was not specifically examined. This

pitfall must be avoided. A forearm film which included

the wrist was obtained. A distal radius fracture and an

ulnar styloid fracture were noted. At the very top of the

film, where it ends, a fracture through the scaphoid was

noted. Patients may not complain of pain exactly over

the fracture site, especially when there are fractures

elsewhere. However, examination for the location(s) of

point tenderness will usually improve the clinician's

ability to locate the site of injury.

View another example.

This radiograph shows another scaphoid fracture.

However even in the absence of such a radiographically

evident fracture, point tenderness over the scaphoid

warrants the same treatment.

View the anatomic snuff box.

This radiograph shows another scaphoid fracture.

However even in the absence of such a radiographically

evident fracture, point tenderness over the scaphoid

warrants the same treatment.

View the anatomic snuff box.

The arrow points to the floor of the anatomic snuff

box. The scaphoid bone forms the floor of the anatomic

snuff box. Tenderness in the area should raise the

suspicion of a scaphoid fracture.

b) The blood supply to the scaphoid penetrates

the cortex at both the distal aspect (on the dorsal

aspect near the scaphoid turbercle) and the waist

(middle third of the scaphoid). Because of this tenuous

blood supply, there is no direct blood supply to the

proximal third of the scaphoid. Therefore, scaphoid

fractures (even if properly diagnosed and treated) have

a tendency for dreaded complications, such as

avascular necrosis of the proximal third and non-union.

In general, the more proximal the fracture, the greater

the likelihood of avascular necrosis.

c) Although adults are more likely to present with

fractures involving the middle third or proximal aspect of

the scaphoid, children have a higher incidence of

fractures involving the distal third of the scaphoid.

d) If one is clinically suspicious of a scaphoid

fracture, always be sure to obtain isolated scaphoid

views in addition to the standard AP, lateral and oblique

views of the wrist. Even if there is no obvious

radiographic evidence of a scaphoid fracture, all

patients with point tenderness over the anatomic snuff

box region should be properly immobilized in the ED

and referred to an orthopedist for further evaluation and

management.

e) Proper immobilization of a scaphoid fracture

should prevent wrist flexion/extension, radial wrist

deviation and any movement of the thumb metacarpal.

Therefore a simple volar wrist splint would NOT be

considered proper immobilization for a scaphoid

fracture. A more adequate immobilization technique

would be to apply a thumb spica/radial gutter splint

(which could also be combined with a volar wrist splint).

View thumb spica/radial gutter splint.

The arrow points to the floor of the anatomic snuff

box. The scaphoid bone forms the floor of the anatomic

snuff box. Tenderness in the area should raise the

suspicion of a scaphoid fracture.

b) The blood supply to the scaphoid penetrates

the cortex at both the distal aspect (on the dorsal

aspect near the scaphoid turbercle) and the waist

(middle third of the scaphoid). Because of this tenuous

blood supply, there is no direct blood supply to the

proximal third of the scaphoid. Therefore, scaphoid

fractures (even if properly diagnosed and treated) have

a tendency for dreaded complications, such as

avascular necrosis of the proximal third and non-union.

In general, the more proximal the fracture, the greater

the likelihood of avascular necrosis.

c) Although adults are more likely to present with

fractures involving the middle third or proximal aspect of

the scaphoid, children have a higher incidence of

fractures involving the distal third of the scaphoid.

d) If one is clinically suspicious of a scaphoid

fracture, always be sure to obtain isolated scaphoid

views in addition to the standard AP, lateral and oblique

views of the wrist. Even if there is no obvious

radiographic evidence of a scaphoid fracture, all

patients with point tenderness over the anatomic snuff

box region should be properly immobilized in the ED

and referred to an orthopedist for further evaluation and

management.

e) Proper immobilization of a scaphoid fracture

should prevent wrist flexion/extension, radial wrist

deviation and any movement of the thumb metacarpal.

Therefore a simple volar wrist splint would NOT be

considered proper immobilization for a scaphoid

fracture. A more adequate immobilization technique

would be to apply a thumb spica/radial gutter splint

(which could also be combined with a volar wrist splint).

View thumb spica/radial gutter splint.

Only the radial gutter and thumb immobilizing

portion of the splint is shown here without the overlying

elastic wrap. The thumb is immobilized to prevent wrist

ab/ad-duction and first metacarpal movement. A volar

splint can be added to this.

f) Definitive treatment by an orthopedic surgeon

usually involves a thumb spica cast for 6-12 weeks.

References

1. Simon RR, Koenigsknecht SJ: Emergency

Orthopedics: The Extremities (second edition).

Appleton & Lange, pp. 81-84, 1987.

2. Letts RM: Management of Pediatric Fractures.

Churchill Livingston, pp. 389-396, 1994.

3. Etzwiler LS. Hand and Wrist Injuries. In:

Barkin R (ed). Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts

and Clinical Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book,

1992, p. 332.

Only the radial gutter and thumb immobilizing

portion of the splint is shown here without the overlying

elastic wrap. The thumb is immobilized to prevent wrist

ab/ad-duction and first metacarpal movement. A volar

splint can be added to this.

f) Definitive treatment by an orthopedic surgeon

usually involves a thumb spica cast for 6-12 weeks.

References

1. Simon RR, Koenigsknecht SJ: Emergency

Orthopedics: The Extremities (second edition).

Appleton & Lange, pp. 81-84, 1987.

2. Letts RM: Management of Pediatric Fractures.

Churchill Livingston, pp. 389-396, 1994.

3. Etzwiler LS. Hand and Wrist Injuries. In:

Barkin R (ed). Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts

and Clinical Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book,

1992, p. 332.