Respiratory Distress - That's a Tension Pneumothorax Isn't It ?

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 1, Case 9

Linda M. Rosen, M.D.

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

A two and one-half week old male infant presents

with a history of distressed noisy breathing for several

hours, progressively worsening with periods of apnea

and cyanosis. He had appeared well all day at the

baby-sitter's until one hour after his last feeding when

he was found to have the symptoms of respiratory

distress. He had no history of fever, URI symptoms,

vomiting, or diarrhea. No possible exposure to toxins or

foreign bodies could be found. Birth history was that of

a full term, NSVD, 7lb. 8oz. born to a 23 y/o G3P2

mother without sepsis risk factors. He seemed to be

doing well since discharge but had been noted by his

parents to have "funny breathing" since birth. This was

described as periodic rapid breathing with "deep caving"

in of his anterior chest. It did not cause cyanosis, nor

did it interfere with feeding. Weight gain since birth has

been appropriate.

Exam VS T36.7, P160, R60, BP 100/70. Oxygen

saturation 86% in room air. He was alert and anxious,

with obvious tachypnea and retractions. Skin color was

intermittently dusky until oxygen was administered and

then remained pink (oxygen saturation 96-100%).

Head atraumatic. No signs of URI. Neck supple.

Suprasternal, intercostal, and subcostal retractions

present. Breath sounds are faint throughout the chest,

without auscultatory rales, wheezes, or stridor heard.

Heart sounds are distant, and no murmur is heard.

Pulses are strong and regular. Capillary refill is brisk.

There are no rashes. Abdominal, neurologic, and

musculoskeletal exams are unremarkable.

A CBC with differential, blood culture, electrolytes,

glucose, UA and CXR are obtained. Room air ABG:

pH 7.33, pCO2 46, pO2 43 in room air. On oxygen by

mask, his pO2 increased to 150. A chest radiograph

is obtained.

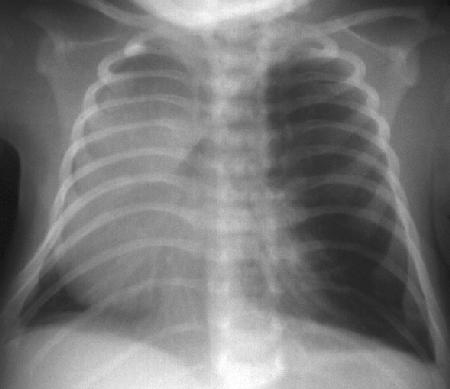

View CXR PA view.

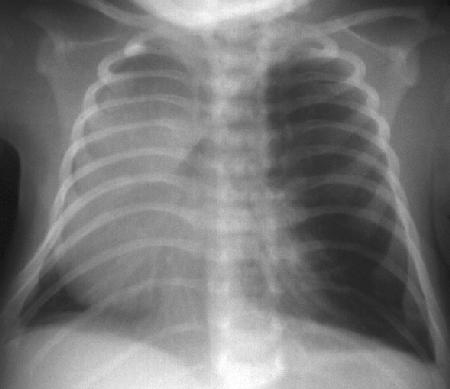

View CXR lateral view.

View CXR lateral view.

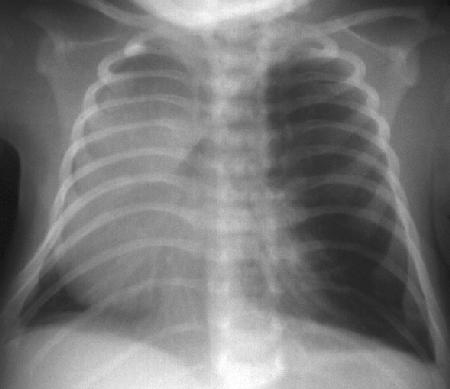

This CXR shows hyperlucency of the left chest with

a mediastinal/cardiac shift to the right.

Management Questions:

This looks like left tension pneumothorax. Should

you perform an emergency needle thoracostomy?

Where would you do it in a 2 1/2 week old?

Before needling the chest (2nd intercostal space,

midclavicular line with an 18 or 20G catheter over the

needle) review the evidence for a tension pneumothorax.

This infant has respiratory distress with hypoxia.

Breath sounds were described as faint throughout the

chest rather than unequal. Is this consistent with a

tension pneumothorax?

Yes, infants with tension pneumothorax rarely have

unequal breath sounds. The intrathoracic volume of the

infant's chest is so small and the mediastinum is so

mobile that decreased ventilation due to free air

compressing both lungs usually results in distant or faint

breath sounds and decreased chest movement

bilaterally, rather than the differential findings between

the two sides seen in adults.

This infant's circulation does not appear

compromised clinically. The patient was alert with good

pulses and capillary refill. Is this consistent with tension

pneumothorax?

No, the hallmark of tension pneumothorax is

persistent hypoxia (despite supplemental oxygen) with

circulatory compromise (hypotension and/or

bradycardia). The fact that this patient did not have

impaired perfusion should make you refrain from

needling the chest and examine the CXR more carefully.

Re-examine the CXR.

This CXR shows hyperlucency of the left chest with

a mediastinal/cardiac shift to the right.

Management Questions:

This looks like left tension pneumothorax. Should

you perform an emergency needle thoracostomy?

Where would you do it in a 2 1/2 week old?

Before needling the chest (2nd intercostal space,

midclavicular line with an 18 or 20G catheter over the

needle) review the evidence for a tension pneumothorax.

This infant has respiratory distress with hypoxia.

Breath sounds were described as faint throughout the

chest rather than unequal. Is this consistent with a

tension pneumothorax?

Yes, infants with tension pneumothorax rarely have

unequal breath sounds. The intrathoracic volume of the

infant's chest is so small and the mediastinum is so

mobile that decreased ventilation due to free air

compressing both lungs usually results in distant or faint

breath sounds and decreased chest movement

bilaterally, rather than the differential findings between

the two sides seen in adults.

This infant's circulation does not appear

compromised clinically. The patient was alert with good

pulses and capillary refill. Is this consistent with tension

pneumothorax?

No, the hallmark of tension pneumothorax is

persistent hypoxia (despite supplemental oxygen) with

circulatory compromise (hypotension and/or

bradycardia). The fact that this patient did not have

impaired perfusion should make you refrain from

needling the chest and examine the CXR more carefully.

Re-examine the CXR.

What at first appears to be a tension pneumothorax

may instead be severe emphysema of one or more

lobes of the lung. Every attempt should be made to

visualize lung markings and the lung edge within the

hyperlucent space. Remember that lung markings

may be very faint because the blood vessels are spread

out. Additionally, there may be reflex hypoxic

vasoconstriction as an attempt to match VQ. Carefully

examining the CXR using a hot light may prevent you

from mistakenly needling the chest and causing a

severe complication. There are indeed lung markings

throughout the left chest (These are evident on the

original film, but it was very difficult to reproduce this on

the scanned image). You decide to intubate the patient

and transfer to the ICU, but the patient's condition

worsens after intubation. What can you do?

If this patient's emphysema becomes life-threatening

(which may happen rapidly if positive pressure is

applied) the only treatment would be a lateral

thoracotomy to allow the lung to herniate out of the

chest. When you call the surgeon, he/she asks if you

are sure this is not hypoplasia of the right lung or

a diaphragmatic hernia. How do you support the

diagnosis of emphysema on CXR?

There are several parameters to assess in order to

answer this question. Before anything else, it is

essential to evaluate the CXR for the presence of any

rotation. A rotated chest film can both mimic and

obscure a mediastinal shift. Evaluation of the clavicles

is one recommended method, but is often confounded

by irregular positioning of both clavicles. Another useful

method is to evaluate the horizontal length of the ribs at

the midchest level measuring from the lateral chest to

the center of the spine on either side. If one side is

longer, the patient is rotated to that side and all

structures will appear to be falsely shifted to the same

side.

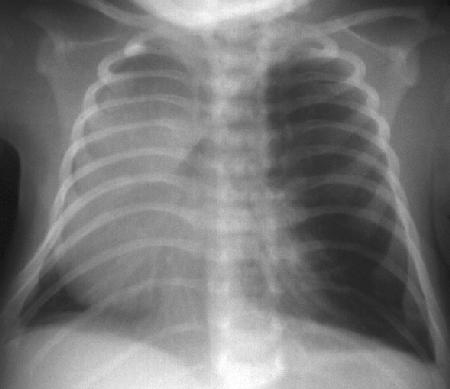

View rotated CXR.

What at first appears to be a tension pneumothorax

may instead be severe emphysema of one or more

lobes of the lung. Every attempt should be made to

visualize lung markings and the lung edge within the

hyperlucent space. Remember that lung markings

may be very faint because the blood vessels are spread

out. Additionally, there may be reflex hypoxic

vasoconstriction as an attempt to match VQ. Carefully

examining the CXR using a hot light may prevent you

from mistakenly needling the chest and causing a

severe complication. There are indeed lung markings

throughout the left chest (These are evident on the

original film, but it was very difficult to reproduce this on

the scanned image). You decide to intubate the patient

and transfer to the ICU, but the patient's condition

worsens after intubation. What can you do?

If this patient's emphysema becomes life-threatening

(which may happen rapidly if positive pressure is

applied) the only treatment would be a lateral

thoracotomy to allow the lung to herniate out of the

chest. When you call the surgeon, he/she asks if you

are sure this is not hypoplasia of the right lung or

a diaphragmatic hernia. How do you support the

diagnosis of emphysema on CXR?

There are several parameters to assess in order to

answer this question. Before anything else, it is

essential to evaluate the CXR for the presence of any

rotation. A rotated chest film can both mimic and

obscure a mediastinal shift. Evaluation of the clavicles

is one recommended method, but is often confounded

by irregular positioning of both clavicles. Another useful

method is to evaluate the horizontal length of the ribs at

the midchest level measuring from the lateral chest to

the center of the spine on either side. If one side is

longer, the patient is rotated to that side and all

structures will appear to be falsely shifted to the same

side.

View rotated CXR.

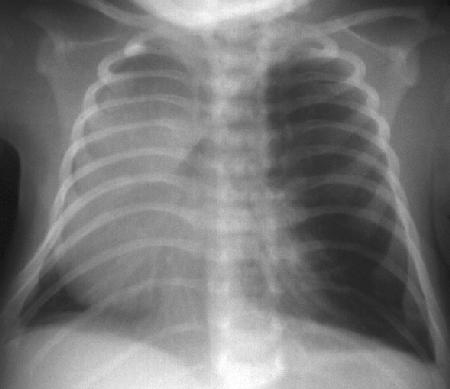

This neonatal CXR is rotated, as can be determined

by looking at the location of the proximal clavicles and

the non-symmetry of the rib origins. This gives the

CXR the appearance of left sided hyperexpansion with

the heart pushed over to the right; however, this

appearance is purely due to rotational artifact.

Once the degree, if any, of rotation has been

determined, several other areas should be evaluated.

The bony thorax may show increased space between

the ribs on one side, indicative of emphysema or

pneumothorax. The diaphragms should be evaluated

for position and evidence of compression or elevation.

A flattened (compressed) hemidiaphragm implies

emphysema of an adjacent lobe or tension

pneumothorax. An elevated hemidiaphragm implies

volume loss in that hemithorax due to atelectasis,

hypoplasia or a diaphragmatic hernia. A decubitus film

can demonstrate failure of the emphysematous lobe to

deflate when placed down. Fluid in the hemithorax will

displace the heart, but would appear radiopaque.

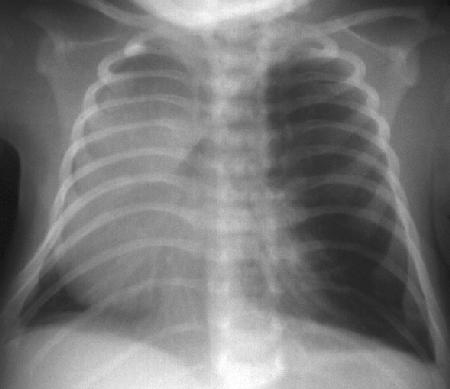

View patient's CXR again.

This neonatal CXR is rotated, as can be determined

by looking at the location of the proximal clavicles and

the non-symmetry of the rib origins. This gives the

CXR the appearance of left sided hyperexpansion with

the heart pushed over to the right; however, this

appearance is purely due to rotational artifact.

Once the degree, if any, of rotation has been

determined, several other areas should be evaluated.

The bony thorax may show increased space between

the ribs on one side, indicative of emphysema or

pneumothorax. The diaphragms should be evaluated

for position and evidence of compression or elevation.

A flattened (compressed) hemidiaphragm implies

emphysema of an adjacent lobe or tension

pneumothorax. An elevated hemidiaphragm implies

volume loss in that hemithorax due to atelectasis,

hypoplasia or a diaphragmatic hernia. A decubitus film

can demonstrate failure of the emphysematous lobe to

deflate when placed down. Fluid in the hemithorax will

displace the heart, but would appear radiopaque.

View patient's CXR again.

Our patient's CXR shows:

1. Hyperexpanded left "lung" (actually the left upper

lobe) that herniates into the right chest.

2. Spreading of ribs of the left chest.

3. Shift of the mediastinum to the right.

4. Compression of the left hemidiaphragm.

5. Left lower lobe atelectasis (It is so small, that you

can hardly see it. It is largely obscured.) visible in the

left inferior medial chest.

6. Normal position of the right hemidiaphragm.

7. No infiltrates or fluid.

8. All these findings are consistent with emphysema

of the left upper lobe.

Discussion

An important aspect of pediatric emergency care is

to be aware of congenital anomalies and the manner

and timing with which they present. The differential

diagnosis of any acute medical presentation in the first

few months of life must include congenital problems.

Within the first weeks of life, respiratory and cardiac

problems often present precipitously.

This patient had congenital lobar emphysema of the

left upper lobe and was also found to have a patent

ductus arteriosus. The history suggests mild symptoms

since birth with acute deterioration. At lobectomy, the

left upper lobe bronchus was noted to have

abnormalities of the cartilage structures. The bronchus

was collapsed with an intraluminal mucous plug.

Emphysema may be caused by cartilaginous

malformation, intrinsic obstruction, or extrinsic

compression. This condition is most common in the

upper lobes and associated in 10% of cases with

congenital heart defects, most commonly patent ductus

arteriosus. Most cases present with respiratory distress

within the first 4 months of life and may eventually

require resection. Occasionally, asymptomatic cases

are found fortuitously on chest radiographs in later

years. Evaluation for coexisting congenital anomalies

may be made through non-invasive tests such as

echocardiography, CT, MRI, and ventilation-perfusion

lung scan.

Additional Teaching Points: Be Aware of . . .

Whenever regional emphysema is present in the

lung, suspicion of a foreign body should be very high.

The young age of our patient made this unlikely but in

the high-risk age group, approximately 5 months to 5

years of age, this diagnosis must be pursued even in

the face of a negative history. Often bronchoscopy is

needed to make the diagnosis and alleviate the

condition. Also, think of a foreign body when faced with

cases of recurrent wheezing or pneumonia (See Case

8 of Volume 1, Foreign Body Aspiration in a Child).

If this infant had a true tension pneumothorax,

staphylococcal pneumonia should be highly suspected.

It is most common in the first six months of life and

often has an extremely rapid onset with fever,

tachypnea, and grunting. Commonly, endobronchial

infection ruptures through to the pleural space, creating

a bronchopleural fistula early in the course of disease,

leading to life-threatening pneumothorax and/or

empyema. This requires urgent placement of a chest

tube, along with appropriate antibiotics and treatment

for septic shock. Staphylococcal pneumonia develops

rapidly and initial CXR findings may show no evident

infiltrate or only a smal amount of pleural fluid.

References

Gerbeaux J, Couvreur J, Tournier G. Pediatric

Respiratory Disease, second edition. New York, J.

Wiley and Sons, 1982, pp. 217-223.

Markowitz RI, Mercurio MR, Vahjen GA, Gross I,

Touloukian RT. Congenital Lobar Emphysema.

Clinical Pediatrics 1989;28(1):19-23.

Scarpeli EM, Auld P, Goldman HS. Pulmonary

Disease of the Fetus, Newborn, and Child.

Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1978, pp. 194-196.

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams &

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1336-1362.

Our patient's CXR shows:

1. Hyperexpanded left "lung" (actually the left upper

lobe) that herniates into the right chest.

2. Spreading of ribs of the left chest.

3. Shift of the mediastinum to the right.

4. Compression of the left hemidiaphragm.

5. Left lower lobe atelectasis (It is so small, that you

can hardly see it. It is largely obscured.) visible in the

left inferior medial chest.

6. Normal position of the right hemidiaphragm.

7. No infiltrates or fluid.

8. All these findings are consistent with emphysema

of the left upper lobe.

Discussion

An important aspect of pediatric emergency care is

to be aware of congenital anomalies and the manner

and timing with which they present. The differential

diagnosis of any acute medical presentation in the first

few months of life must include congenital problems.

Within the first weeks of life, respiratory and cardiac

problems often present precipitously.

This patient had congenital lobar emphysema of the

left upper lobe and was also found to have a patent

ductus arteriosus. The history suggests mild symptoms

since birth with acute deterioration. At lobectomy, the

left upper lobe bronchus was noted to have

abnormalities of the cartilage structures. The bronchus

was collapsed with an intraluminal mucous plug.

Emphysema may be caused by cartilaginous

malformation, intrinsic obstruction, or extrinsic

compression. This condition is most common in the

upper lobes and associated in 10% of cases with

congenital heart defects, most commonly patent ductus

arteriosus. Most cases present with respiratory distress

within the first 4 months of life and may eventually

require resection. Occasionally, asymptomatic cases

are found fortuitously on chest radiographs in later

years. Evaluation for coexisting congenital anomalies

may be made through non-invasive tests such as

echocardiography, CT, MRI, and ventilation-perfusion

lung scan.

Additional Teaching Points: Be Aware of . . .

Whenever regional emphysema is present in the

lung, suspicion of a foreign body should be very high.

The young age of our patient made this unlikely but in

the high-risk age group, approximately 5 months to 5

years of age, this diagnosis must be pursued even in

the face of a negative history. Often bronchoscopy is

needed to make the diagnosis and alleviate the

condition. Also, think of a foreign body when faced with

cases of recurrent wheezing or pneumonia (See Case

8 of Volume 1, Foreign Body Aspiration in a Child).

If this infant had a true tension pneumothorax,

staphylococcal pneumonia should be highly suspected.

It is most common in the first six months of life and

often has an extremely rapid onset with fever,

tachypnea, and grunting. Commonly, endobronchial

infection ruptures through to the pleural space, creating

a bronchopleural fistula early in the course of disease,

leading to life-threatening pneumothorax and/or

empyema. This requires urgent placement of a chest

tube, along with appropriate antibiotics and treatment

for septic shock. Staphylococcal pneumonia develops

rapidly and initial CXR findings may show no evident

infiltrate or only a smal amount of pleural fluid.

References

Gerbeaux J, Couvreur J, Tournier G. Pediatric

Respiratory Disease, second edition. New York, J.

Wiley and Sons, 1982, pp. 217-223.

Markowitz RI, Mercurio MR, Vahjen GA, Gross I,

Touloukian RT. Congenital Lobar Emphysema.

Clinical Pediatrics 1989;28(1):19-23.

Scarpeli EM, Auld P, Goldman HS. Pulmonary

Disease of the Fetus, Newborn, and Child.

Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1978, pp. 194-196.

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams &

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1336-1362.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

View CXR lateral view.

View CXR lateral view.

This CXR shows hyperlucency of the left chest with

a mediastinal/cardiac shift to the right.

Management Questions:

This looks like left tension pneumothorax. Should

you perform an emergency needle thoracostomy?

Where would you do it in a 2 1/2 week old?

Before needling the chest (2nd intercostal space,

midclavicular line with an 18 or 20G catheter over the

needle) review the evidence for a tension pneumothorax.

This infant has respiratory distress with hypoxia.

Breath sounds were described as faint throughout the

chest rather than unequal. Is this consistent with a

tension pneumothorax?

Yes, infants with tension pneumothorax rarely have

unequal breath sounds. The intrathoracic volume of the

infant's chest is so small and the mediastinum is so

mobile that decreased ventilation due to free air

compressing both lungs usually results in distant or faint

breath sounds and decreased chest movement

bilaterally, rather than the differential findings between

the two sides seen in adults.

This infant's circulation does not appear

compromised clinically. The patient was alert with good

pulses and capillary refill. Is this consistent with tension

pneumothorax?

No, the hallmark of tension pneumothorax is

persistent hypoxia (despite supplemental oxygen) with

circulatory compromise (hypotension and/or

bradycardia). The fact that this patient did not have

impaired perfusion should make you refrain from

needling the chest and examine the CXR more carefully.

Re-examine the CXR.

This CXR shows hyperlucency of the left chest with

a mediastinal/cardiac shift to the right.

Management Questions:

This looks like left tension pneumothorax. Should

you perform an emergency needle thoracostomy?

Where would you do it in a 2 1/2 week old?

Before needling the chest (2nd intercostal space,

midclavicular line with an 18 or 20G catheter over the

needle) review the evidence for a tension pneumothorax.

This infant has respiratory distress with hypoxia.

Breath sounds were described as faint throughout the

chest rather than unequal. Is this consistent with a

tension pneumothorax?

Yes, infants with tension pneumothorax rarely have

unequal breath sounds. The intrathoracic volume of the

infant's chest is so small and the mediastinum is so

mobile that decreased ventilation due to free air

compressing both lungs usually results in distant or faint

breath sounds and decreased chest movement

bilaterally, rather than the differential findings between

the two sides seen in adults.

This infant's circulation does not appear

compromised clinically. The patient was alert with good

pulses and capillary refill. Is this consistent with tension

pneumothorax?

No, the hallmark of tension pneumothorax is

persistent hypoxia (despite supplemental oxygen) with

circulatory compromise (hypotension and/or

bradycardia). The fact that this patient did not have

impaired perfusion should make you refrain from

needling the chest and examine the CXR more carefully.

Re-examine the CXR.

What at first appears to be a tension pneumothorax

may instead be severe emphysema of one or more

lobes of the lung. Every attempt should be made to

visualize lung markings and the lung edge within the

hyperlucent space. Remember that lung markings

may be very faint because the blood vessels are spread

out. Additionally, there may be reflex hypoxic

vasoconstriction as an attempt to match VQ. Carefully

examining the CXR using a hot light may prevent you

from mistakenly needling the chest and causing a

severe complication. There are indeed lung markings

throughout the left chest (These are evident on the

original film, but it was very difficult to reproduce this on

the scanned image). You decide to intubate the patient

and transfer to the ICU, but the patient's condition

worsens after intubation. What can you do?

If this patient's emphysema becomes life-threatening

(which may happen rapidly if positive pressure is

applied) the only treatment would be a lateral

thoracotomy to allow the lung to herniate out of the

chest. When you call the surgeon, he/she asks if you

are sure this is not hypoplasia of the right lung or

a diaphragmatic hernia. How do you support the

diagnosis of emphysema on CXR?

There are several parameters to assess in order to

answer this question. Before anything else, it is

essential to evaluate the CXR for the presence of any

rotation. A rotated chest film can both mimic and

obscure a mediastinal shift. Evaluation of the clavicles

is one recommended method, but is often confounded

by irregular positioning of both clavicles. Another useful

method is to evaluate the horizontal length of the ribs at

the midchest level measuring from the lateral chest to

the center of the spine on either side. If one side is

longer, the patient is rotated to that side and all

structures will appear to be falsely shifted to the same

side.

View rotated CXR.

What at first appears to be a tension pneumothorax

may instead be severe emphysema of one or more

lobes of the lung. Every attempt should be made to

visualize lung markings and the lung edge within the

hyperlucent space. Remember that lung markings

may be very faint because the blood vessels are spread

out. Additionally, there may be reflex hypoxic

vasoconstriction as an attempt to match VQ. Carefully

examining the CXR using a hot light may prevent you

from mistakenly needling the chest and causing a

severe complication. There are indeed lung markings

throughout the left chest (These are evident on the

original film, but it was very difficult to reproduce this on

the scanned image). You decide to intubate the patient

and transfer to the ICU, but the patient's condition

worsens after intubation. What can you do?

If this patient's emphysema becomes life-threatening

(which may happen rapidly if positive pressure is

applied) the only treatment would be a lateral

thoracotomy to allow the lung to herniate out of the

chest. When you call the surgeon, he/she asks if you

are sure this is not hypoplasia of the right lung or

a diaphragmatic hernia. How do you support the

diagnosis of emphysema on CXR?

There are several parameters to assess in order to

answer this question. Before anything else, it is

essential to evaluate the CXR for the presence of any

rotation. A rotated chest film can both mimic and

obscure a mediastinal shift. Evaluation of the clavicles

is one recommended method, but is often confounded

by irregular positioning of both clavicles. Another useful

method is to evaluate the horizontal length of the ribs at

the midchest level measuring from the lateral chest to

the center of the spine on either side. If one side is

longer, the patient is rotated to that side and all

structures will appear to be falsely shifted to the same

side.

View rotated CXR.

This neonatal CXR is rotated, as can be determined

by looking at the location of the proximal clavicles and

the non-symmetry of the rib origins. This gives the

CXR the appearance of left sided hyperexpansion with

the heart pushed over to the right; however, this

appearance is purely due to rotational artifact.

Once the degree, if any, of rotation has been

determined, several other areas should be evaluated.

The bony thorax may show increased space between

the ribs on one side, indicative of emphysema or

pneumothorax. The diaphragms should be evaluated

for position and evidence of compression or elevation.

A flattened (compressed) hemidiaphragm implies

emphysema of an adjacent lobe or tension

pneumothorax. An elevated hemidiaphragm implies

volume loss in that hemithorax due to atelectasis,

hypoplasia or a diaphragmatic hernia. A decubitus film

can demonstrate failure of the emphysematous lobe to

deflate when placed down. Fluid in the hemithorax will

displace the heart, but would appear radiopaque.

View patient's CXR again.

This neonatal CXR is rotated, as can be determined

by looking at the location of the proximal clavicles and

the non-symmetry of the rib origins. This gives the

CXR the appearance of left sided hyperexpansion with

the heart pushed over to the right; however, this

appearance is purely due to rotational artifact.

Once the degree, if any, of rotation has been

determined, several other areas should be evaluated.

The bony thorax may show increased space between

the ribs on one side, indicative of emphysema or

pneumothorax. The diaphragms should be evaluated

for position and evidence of compression or elevation.

A flattened (compressed) hemidiaphragm implies

emphysema of an adjacent lobe or tension

pneumothorax. An elevated hemidiaphragm implies

volume loss in that hemithorax due to atelectasis,

hypoplasia or a diaphragmatic hernia. A decubitus film

can demonstrate failure of the emphysematous lobe to

deflate when placed down. Fluid in the hemithorax will

displace the heart, but would appear radiopaque.

View patient's CXR again.

Our patient's CXR shows:

1. Hyperexpanded left "lung" (actually the left upper

lobe) that herniates into the right chest.

2. Spreading of ribs of the left chest.

3. Shift of the mediastinum to the right.

4. Compression of the left hemidiaphragm.

5. Left lower lobe atelectasis (It is so small, that you

can hardly see it. It is largely obscured.) visible in the

left inferior medial chest.

6. Normal position of the right hemidiaphragm.

7. No infiltrates or fluid.

8. All these findings are consistent with emphysema

of the left upper lobe.

Discussion

An important aspect of pediatric emergency care is

to be aware of congenital anomalies and the manner

and timing with which they present. The differential

diagnosis of any acute medical presentation in the first

few months of life must include congenital problems.

Within the first weeks of life, respiratory and cardiac

problems often present precipitously.

This patient had congenital lobar emphysema of the

left upper lobe and was also found to have a patent

ductus arteriosus. The history suggests mild symptoms

since birth with acute deterioration. At lobectomy, the

left upper lobe bronchus was noted to have

abnormalities of the cartilage structures. The bronchus

was collapsed with an intraluminal mucous plug.

Emphysema may be caused by cartilaginous

malformation, intrinsic obstruction, or extrinsic

compression. This condition is most common in the

upper lobes and associated in 10% of cases with

congenital heart defects, most commonly patent ductus

arteriosus. Most cases present with respiratory distress

within the first 4 months of life and may eventually

require resection. Occasionally, asymptomatic cases

are found fortuitously on chest radiographs in later

years. Evaluation for coexisting congenital anomalies

may be made through non-invasive tests such as

echocardiography, CT, MRI, and ventilation-perfusion

lung scan.

Additional Teaching Points: Be Aware of . . .

Whenever regional emphysema is present in the

lung, suspicion of a foreign body should be very high.

The young age of our patient made this unlikely but in

the high-risk age group, approximately 5 months to 5

years of age, this diagnosis must be pursued even in

the face of a negative history. Often bronchoscopy is

needed to make the diagnosis and alleviate the

condition. Also, think of a foreign body when faced with

cases of recurrent wheezing or pneumonia (See Case

8 of Volume 1, Foreign Body Aspiration in a Child).

If this infant had a true tension pneumothorax,

staphylococcal pneumonia should be highly suspected.

It is most common in the first six months of life and

often has an extremely rapid onset with fever,

tachypnea, and grunting. Commonly, endobronchial

infection ruptures through to the pleural space, creating

a bronchopleural fistula early in the course of disease,

leading to life-threatening pneumothorax and/or

empyema. This requires urgent placement of a chest

tube, along with appropriate antibiotics and treatment

for septic shock. Staphylococcal pneumonia develops

rapidly and initial CXR findings may show no evident

infiltrate or only a smal amount of pleural fluid.

References

Gerbeaux J, Couvreur J, Tournier G. Pediatric

Respiratory Disease, second edition. New York, J.

Wiley and Sons, 1982, pp. 217-223.

Markowitz RI, Mercurio MR, Vahjen GA, Gross I,

Touloukian RT. Congenital Lobar Emphysema.

Clinical Pediatrics 1989;28(1):19-23.

Scarpeli EM, Auld P, Goldman HS. Pulmonary

Disease of the Fetus, Newborn, and Child.

Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1978, pp. 194-196.

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams &

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1336-1362.

Our patient's CXR shows:

1. Hyperexpanded left "lung" (actually the left upper

lobe) that herniates into the right chest.

2. Spreading of ribs of the left chest.

3. Shift of the mediastinum to the right.

4. Compression of the left hemidiaphragm.

5. Left lower lobe atelectasis (It is so small, that you

can hardly see it. It is largely obscured.) visible in the

left inferior medial chest.

6. Normal position of the right hemidiaphragm.

7. No infiltrates or fluid.

8. All these findings are consistent with emphysema

of the left upper lobe.

Discussion

An important aspect of pediatric emergency care is

to be aware of congenital anomalies and the manner

and timing with which they present. The differential

diagnosis of any acute medical presentation in the first

few months of life must include congenital problems.

Within the first weeks of life, respiratory and cardiac

problems often present precipitously.

This patient had congenital lobar emphysema of the

left upper lobe and was also found to have a patent

ductus arteriosus. The history suggests mild symptoms

since birth with acute deterioration. At lobectomy, the

left upper lobe bronchus was noted to have

abnormalities of the cartilage structures. The bronchus

was collapsed with an intraluminal mucous plug.

Emphysema may be caused by cartilaginous

malformation, intrinsic obstruction, or extrinsic

compression. This condition is most common in the

upper lobes and associated in 10% of cases with

congenital heart defects, most commonly patent ductus

arteriosus. Most cases present with respiratory distress

within the first 4 months of life and may eventually

require resection. Occasionally, asymptomatic cases

are found fortuitously on chest radiographs in later

years. Evaluation for coexisting congenital anomalies

may be made through non-invasive tests such as

echocardiography, CT, MRI, and ventilation-perfusion

lung scan.

Additional Teaching Points: Be Aware of . . .

Whenever regional emphysema is present in the

lung, suspicion of a foreign body should be very high.

The young age of our patient made this unlikely but in

the high-risk age group, approximately 5 months to 5

years of age, this diagnosis must be pursued even in

the face of a negative history. Often bronchoscopy is

needed to make the diagnosis and alleviate the

condition. Also, think of a foreign body when faced with

cases of recurrent wheezing or pneumonia (See Case

8 of Volume 1, Foreign Body Aspiration in a Child).

If this infant had a true tension pneumothorax,

staphylococcal pneumonia should be highly suspected.

It is most common in the first six months of life and

often has an extremely rapid onset with fever,

tachypnea, and grunting. Commonly, endobronchial

infection ruptures through to the pleural space, creating

a bronchopleural fistula early in the course of disease,

leading to life-threatening pneumothorax and/or

empyema. This requires urgent placement of a chest

tube, along with appropriate antibiotics and treatment

for septic shock. Staphylococcal pneumonia develops

rapidly and initial CXR findings may show no evident

infiltrate or only a smal amount of pleural fluid.

References

Gerbeaux J, Couvreur J, Tournier G. Pediatric

Respiratory Disease, second edition. New York, J.

Wiley and Sons, 1982, pp. 217-223.

Markowitz RI, Mercurio MR, Vahjen GA, Gross I,

Touloukian RT. Congenital Lobar Emphysema.

Clinical Pediatrics 1989;28(1):19-23.

Scarpeli EM, Auld P, Goldman HS. Pulmonary

Disease of the Fetus, Newborn, and Child.

Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1978, pp. 194-196.

Templeton JM. Thoracic Emergencies. In: Fleisher

GR, Ludwig S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams &

Wilkins, 1993, pp. 1336-1362.