Foreign Body Aspiration in a Child

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 1, Case 8

Rodney B. Boychuk, MD

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

A 17 month old male presents to the ED in the

evening with a one-hour history of noisy and abnormal

breathing after a choking episode while he was eating a

chocolate and almond bar. He was able to speak and

drink fluids without difficulty.

Exam: VS T36.8, P200 (crying), R28 (crying),

oxygen saturation 99% in room air. He appeared alert,

with no signs of respiratory distress. He was able to

speak, had no cyanosis, no drooling, and no dyspnea.

His lung sounds showed mild wheezing with possible

mild inspiratory stridor. An albuterol aerosol was

administered but no improvement was noted. A

chest radiograph was ordered.

View CXR.

Questions:

1. Are any foreign bodies visible on this radiograph?

2. Are there any subtle findings on this radiograph

to suggest a foreign body?

3. Are there other radiologic procedures that can be

done to try to identify a foreign body?

4. Is an invasive procedure necessary or indicated

at this point, i.e., bronchoscopy?

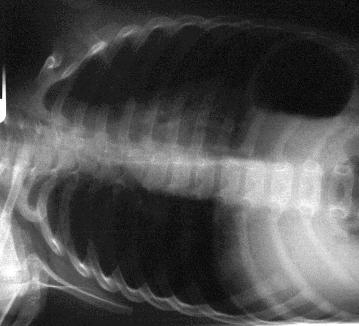

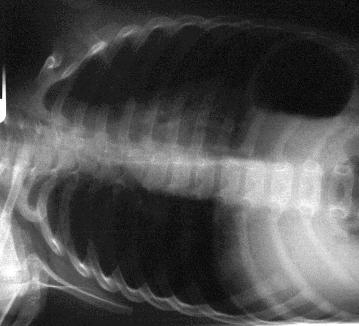

This CXR is within normal limits; however, when a

clinical suspicion of an airway foreign body is present,

a standard PA and lateral CXR are an insufficient

evaluation. A lateral neck film should be obtained to

examine the upper airway for evidence of swelling or

foreign body. Decubitus films and/or expiratory films

should also be obtained to look for evidence of air

trapping.

View supplementary radiographs.

Lateral neck.

Questions:

1. Are any foreign bodies visible on this radiograph?

2. Are there any subtle findings on this radiograph

to suggest a foreign body?

3. Are there other radiologic procedures that can be

done to try to identify a foreign body?

4. Is an invasive procedure necessary or indicated

at this point, i.e., bronchoscopy?

This CXR is within normal limits; however, when a

clinical suspicion of an airway foreign body is present,

a standard PA and lateral CXR are an insufficient

evaluation. A lateral neck film should be obtained to

examine the upper airway for evidence of swelling or

foreign body. Decubitus films and/or expiratory films

should also be obtained to look for evidence of air

trapping.

View supplementary radiographs.

Lateral neck.

Expiratory Chest.

Expiratory Chest.

Left lateral decubitus.

Left lateral decubitus.

Right lateral decubitus.

Right lateral decubitus.

The lateral neck radiograph is within normal limits.

The black dots in the upper right are pointing to a

metallic object in the holder's watch band.

These other radiographs were interpreted as

possible bilateral air trapping.

The expiratory view is fairly symmetric in this

instance. A foreign body in a bronchus is expected to

show air trapping with some hyperexpansion visible in

that lung. In the expiratory view, both lung volumes

should normally be decreased. If one side is still

expanded during expiration, this indicates air trapping

and a possible foreign body on that side.

An expiratory CXR that shows symmetry of both

lung volumes does not rule out a foreign body. Such a

CXR is often assumed to be consistent with asthma.

Although this is often true, this is occasionally a pitfall

that should be avoided by considering such a CXR to

also be consistent with a tracheal foreign body.

Examine the expiratory CXR again. It shows that both

lungs empty poorly, indicating bilateral air trapping.

This could be consistent with asthma or with a tracheal

foreign body.

The left lateral decubitus view (left side down) shows

the left lung volume to be somewhat smaller than the

right lung volume. However, one might expect the left

lung to be even smaller in the dependent position, so

perhaps it isn't as small as it should be. This suggests

some degree of air trapping on the left.

The right lateral decubitus view (right side down)

is of poor quality. The original film was very dark so

the scanned image is very grainy. This shows the right

lung to be clearly expanded even though it is

dependent. This suggests air trapping since a normal

lung should appear smaller in the dependent position.

The patient was taken to the operating room for

bronchoscopy. At bronchoscopy, about 15-20 pieces of

nut particles in the lower trachea and in both major

bronchi were found. They were somewhat difficult to

remove because of their small size. Most were

removed with grasping forceps and suction. He did well

postoperatively.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Approximately 75% of all cases of foreign body

aspiration occur in children less than 3 years of age.

Organic debris is most frequently retrieved on

bronchoscopy. Peanuts are the most common

offending agent. Unfortunately, only 6-17% of airway

foreign bodies are radio-opaque. Respiratory

symptoms may be produced by an object lodged

anywhere in the airway, from the hypopharynx to a

segmental bronchus.

Children who ingest or aspirate foreign bodies may

present in acute respiratory distress days or months

after the aspiration episode. Between 50% and 90% of

children have a suggestive history, most commonly of

an acute episode of paroxysmal cough. Other common

signs are cyanosis, choking, and dyspnea. However,

delays in presentation for care are common, and

concern about aspiration as a cause of the child's

symptoms may diminish as the primary event becomes

more distant. Only half of all children are diagnosed

correctly in the first 24 hours after an aspiration event.

An additional 30% receive the correct diagnosis in the

following week, while the remainder may have delays in

diagnosis of weeks to years. One-fourth of children

may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation, and

up to 38% may have no helpful physical exam findings.

The complete triad of coughing, wheezing, and

decreased or absent breath sounds is present in only

about 40% of cases. Other suggestive physical exam

findings are stridor, tachypnea, retractions, rales, and

fever. They are often misdiagnosed as croup, asthma,

pneumonia, or bronchitis. This is a diagnostic pitfall

that should be avoided. Thus, the diagnosis of foreign

body aspiration must be considered in any previously

well, child who has a history of acute onset of choking,

coughing, or wheezing, as well as any child who has a

poorly defined, chronic respiratory complaint.

Remember this general principle:

Nuts + Choking = Bronchoscopy

(regardless of radiographic results)

Roughly 85% of foreign bodies are bronchial, while

15% are laryngotracheal. Laryngotracheal foreign

bodies are more difficult to diagnose and they have a

higher mortality rate. Differential findings, clinically or

radiographically, may only be present in unilateral

bronchial foreign bodies. Differential findings are often

absent in bilateral bronchial foreign bodies or

laryngotracheal foreign bodies. Additionally, foreign

bodies may shift in position. Thus, a previously

suspicious radiographic study may be negative if it is

repeated. One cannot assume that such a patient is

now normal since a more likely explanation is that the

foreign body has moved. Avoid this pitfall.

Although appropriate radiologic studies may localize

the site of the foreign body, a significant number of

children with retained airway foreign bodies have

non-diagnostic films. Radiologic evaluation should start

with AP and lateral views of the chest and neck.

Although plain films may be interpreted as normal,

differential inflation of the affected lung, the most

common abnormality identified, may be documented by

fluoroscopy, lateral decubitus views, or an assisted

expiratory film (the examiner compresses the patient's

abdomen during expiration). Other indirect signs of an

airway foreign body include reabsorption atelectasis

beyond the site of bronchial obstruction, and the

presence of pulmonary infiltrates reflecting an

inflammatory reaction. One source (Esclamado)

reported positive findings on chest radiographs in only

42% of children with laryngotracheal (as opposed to

bronchial) foreign bodies, but a higher rate of positive

findings on lateral neck films in the same series. This

emphasizes the need to direct the examination to the

neck (ie., lateral neck view) when signs of upper airway

obstruction are present. Esophageal foreign bodies

may also cause predominantly respiratory symptoms.

Although CT scan, xeroradiography, and

ultrasonography have been advocated for foreign body

imaging, their utility is not well defined at this time.

CT scanning may be non diagnostic because of

respiratory motion (resulting in poor images) and such

patients usually require sedation which can be risky in

the presence of airway compromise. Given the high

morbidity associated with delay in the diagnosis of an

airway foreign body, and the limited sensitivity of

radiographic studies in identifying this condition, clinical

judgment must dictate whether the child should be

scheduled for diagnostic bronchoscopy in the absence

of radiographic findings.

References

Schunk JE. Foreign Body-Ingestion/Aspiration. In:

Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric

Emergency Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams

& Wilkins, 1993, pp. 210-217.

Brownstein D. Foreign Bodies of the

Gastrointestinal Tract and Airway. In: Barkin R (ed).

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical

Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book, 1992, pp.

311-314.

Hamilton AH, Carswell F, Wisheart JD. The Bristol

Children's Experience of Tracheobronchial Foreign

Bodies 1977-87. Bristol Med Chir Journal 1989;104:72.

Esclamado RM, Richardson MA. Laryngotracheal

Foreign Bodies in Children. American Journal of

Diseases in Children 1987;141:259.

The lateral neck radiograph is within normal limits.

The black dots in the upper right are pointing to a

metallic object in the holder's watch band.

These other radiographs were interpreted as

possible bilateral air trapping.

The expiratory view is fairly symmetric in this

instance. A foreign body in a bronchus is expected to

show air trapping with some hyperexpansion visible in

that lung. In the expiratory view, both lung volumes

should normally be decreased. If one side is still

expanded during expiration, this indicates air trapping

and a possible foreign body on that side.

An expiratory CXR that shows symmetry of both

lung volumes does not rule out a foreign body. Such a

CXR is often assumed to be consistent with asthma.

Although this is often true, this is occasionally a pitfall

that should be avoided by considering such a CXR to

also be consistent with a tracheal foreign body.

Examine the expiratory CXR again. It shows that both

lungs empty poorly, indicating bilateral air trapping.

This could be consistent with asthma or with a tracheal

foreign body.

The left lateral decubitus view (left side down) shows

the left lung volume to be somewhat smaller than the

right lung volume. However, one might expect the left

lung to be even smaller in the dependent position, so

perhaps it isn't as small as it should be. This suggests

some degree of air trapping on the left.

The right lateral decubitus view (right side down)

is of poor quality. The original film was very dark so

the scanned image is very grainy. This shows the right

lung to be clearly expanded even though it is

dependent. This suggests air trapping since a normal

lung should appear smaller in the dependent position.

The patient was taken to the operating room for

bronchoscopy. At bronchoscopy, about 15-20 pieces of

nut particles in the lower trachea and in both major

bronchi were found. They were somewhat difficult to

remove because of their small size. Most were

removed with grasping forceps and suction. He did well

postoperatively.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Approximately 75% of all cases of foreign body

aspiration occur in children less than 3 years of age.

Organic debris is most frequently retrieved on

bronchoscopy. Peanuts are the most common

offending agent. Unfortunately, only 6-17% of airway

foreign bodies are radio-opaque. Respiratory

symptoms may be produced by an object lodged

anywhere in the airway, from the hypopharynx to a

segmental bronchus.

Children who ingest or aspirate foreign bodies may

present in acute respiratory distress days or months

after the aspiration episode. Between 50% and 90% of

children have a suggestive history, most commonly of

an acute episode of paroxysmal cough. Other common

signs are cyanosis, choking, and dyspnea. However,

delays in presentation for care are common, and

concern about aspiration as a cause of the child's

symptoms may diminish as the primary event becomes

more distant. Only half of all children are diagnosed

correctly in the first 24 hours after an aspiration event.

An additional 30% receive the correct diagnosis in the

following week, while the remainder may have delays in

diagnosis of weeks to years. One-fourth of children

may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation, and

up to 38% may have no helpful physical exam findings.

The complete triad of coughing, wheezing, and

decreased or absent breath sounds is present in only

about 40% of cases. Other suggestive physical exam

findings are stridor, tachypnea, retractions, rales, and

fever. They are often misdiagnosed as croup, asthma,

pneumonia, or bronchitis. This is a diagnostic pitfall

that should be avoided. Thus, the diagnosis of foreign

body aspiration must be considered in any previously

well, child who has a history of acute onset of choking,

coughing, or wheezing, as well as any child who has a

poorly defined, chronic respiratory complaint.

Remember this general principle:

Nuts + Choking = Bronchoscopy

(regardless of radiographic results)

Roughly 85% of foreign bodies are bronchial, while

15% are laryngotracheal. Laryngotracheal foreign

bodies are more difficult to diagnose and they have a

higher mortality rate. Differential findings, clinically or

radiographically, may only be present in unilateral

bronchial foreign bodies. Differential findings are often

absent in bilateral bronchial foreign bodies or

laryngotracheal foreign bodies. Additionally, foreign

bodies may shift in position. Thus, a previously

suspicious radiographic study may be negative if it is

repeated. One cannot assume that such a patient is

now normal since a more likely explanation is that the

foreign body has moved. Avoid this pitfall.

Although appropriate radiologic studies may localize

the site of the foreign body, a significant number of

children with retained airway foreign bodies have

non-diagnostic films. Radiologic evaluation should start

with AP and lateral views of the chest and neck.

Although plain films may be interpreted as normal,

differential inflation of the affected lung, the most

common abnormality identified, may be documented by

fluoroscopy, lateral decubitus views, or an assisted

expiratory film (the examiner compresses the patient's

abdomen during expiration). Other indirect signs of an

airway foreign body include reabsorption atelectasis

beyond the site of bronchial obstruction, and the

presence of pulmonary infiltrates reflecting an

inflammatory reaction. One source (Esclamado)

reported positive findings on chest radiographs in only

42% of children with laryngotracheal (as opposed to

bronchial) foreign bodies, but a higher rate of positive

findings on lateral neck films in the same series. This

emphasizes the need to direct the examination to the

neck (ie., lateral neck view) when signs of upper airway

obstruction are present. Esophageal foreign bodies

may also cause predominantly respiratory symptoms.

Although CT scan, xeroradiography, and

ultrasonography have been advocated for foreign body

imaging, their utility is not well defined at this time.

CT scanning may be non diagnostic because of

respiratory motion (resulting in poor images) and such

patients usually require sedation which can be risky in

the presence of airway compromise. Given the high

morbidity associated with delay in the diagnosis of an

airway foreign body, and the limited sensitivity of

radiographic studies in identifying this condition, clinical

judgment must dictate whether the child should be

scheduled for diagnostic bronchoscopy in the absence

of radiographic findings.

References

Schunk JE. Foreign Body-Ingestion/Aspiration. In:

Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric

Emergency Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams

& Wilkins, 1993, pp. 210-217.

Brownstein D. Foreign Bodies of the

Gastrointestinal Tract and Airway. In: Barkin R (ed).

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical

Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book, 1992, pp.

311-314.

Hamilton AH, Carswell F, Wisheart JD. The Bristol

Children's Experience of Tracheobronchial Foreign

Bodies 1977-87. Bristol Med Chir Journal 1989;104:72.

Esclamado RM, Richardson MA. Laryngotracheal

Foreign Bodies in Children. American Journal of

Diseases in Children 1987;141:259.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

Questions:

1. Are any foreign bodies visible on this radiograph?

2. Are there any subtle findings on this radiograph

to suggest a foreign body?

3. Are there other radiologic procedures that can be

done to try to identify a foreign body?

4. Is an invasive procedure necessary or indicated

at this point, i.e., bronchoscopy?

This CXR is within normal limits; however, when a

clinical suspicion of an airway foreign body is present,

a standard PA and lateral CXR are an insufficient

evaluation. A lateral neck film should be obtained to

examine the upper airway for evidence of swelling or

foreign body. Decubitus films and/or expiratory films

should also be obtained to look for evidence of air

trapping.

View supplementary radiographs.

Lateral neck.

Questions:

1. Are any foreign bodies visible on this radiograph?

2. Are there any subtle findings on this radiograph

to suggest a foreign body?

3. Are there other radiologic procedures that can be

done to try to identify a foreign body?

4. Is an invasive procedure necessary or indicated

at this point, i.e., bronchoscopy?

This CXR is within normal limits; however, when a

clinical suspicion of an airway foreign body is present,

a standard PA and lateral CXR are an insufficient

evaluation. A lateral neck film should be obtained to

examine the upper airway for evidence of swelling or

foreign body. Decubitus films and/or expiratory films

should also be obtained to look for evidence of air

trapping.

View supplementary radiographs.

Lateral neck.

Expiratory Chest.

Expiratory Chest.

Left lateral decubitus.

Left lateral decubitus.

Right lateral decubitus.

Right lateral decubitus.

The lateral neck radiograph is within normal limits.

The black dots in the upper right are pointing to a

metallic object in the holder's watch band.

These other radiographs were interpreted as

possible bilateral air trapping.

The expiratory view is fairly symmetric in this

instance. A foreign body in a bronchus is expected to

show air trapping with some hyperexpansion visible in

that lung. In the expiratory view, both lung volumes

should normally be decreased. If one side is still

expanded during expiration, this indicates air trapping

and a possible foreign body on that side.

An expiratory CXR that shows symmetry of both

lung volumes does not rule out a foreign body. Such a

CXR is often assumed to be consistent with asthma.

Although this is often true, this is occasionally a pitfall

that should be avoided by considering such a CXR to

also be consistent with a tracheal foreign body.

Examine the expiratory CXR again. It shows that both

lungs empty poorly, indicating bilateral air trapping.

This could be consistent with asthma or with a tracheal

foreign body.

The left lateral decubitus view (left side down) shows

the left lung volume to be somewhat smaller than the

right lung volume. However, one might expect the left

lung to be even smaller in the dependent position, so

perhaps it isn't as small as it should be. This suggests

some degree of air trapping on the left.

The right lateral decubitus view (right side down)

is of poor quality. The original film was very dark so

the scanned image is very grainy. This shows the right

lung to be clearly expanded even though it is

dependent. This suggests air trapping since a normal

lung should appear smaller in the dependent position.

The patient was taken to the operating room for

bronchoscopy. At bronchoscopy, about 15-20 pieces of

nut particles in the lower trachea and in both major

bronchi were found. They were somewhat difficult to

remove because of their small size. Most were

removed with grasping forceps and suction. He did well

postoperatively.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Approximately 75% of all cases of foreign body

aspiration occur in children less than 3 years of age.

Organic debris is most frequently retrieved on

bronchoscopy. Peanuts are the most common

offending agent. Unfortunately, only 6-17% of airway

foreign bodies are radio-opaque. Respiratory

symptoms may be produced by an object lodged

anywhere in the airway, from the hypopharynx to a

segmental bronchus.

Children who ingest or aspirate foreign bodies may

present in acute respiratory distress days or months

after the aspiration episode. Between 50% and 90% of

children have a suggestive history, most commonly of

an acute episode of paroxysmal cough. Other common

signs are cyanosis, choking, and dyspnea. However,

delays in presentation for care are common, and

concern about aspiration as a cause of the child's

symptoms may diminish as the primary event becomes

more distant. Only half of all children are diagnosed

correctly in the first 24 hours after an aspiration event.

An additional 30% receive the correct diagnosis in the

following week, while the remainder may have delays in

diagnosis of weeks to years. One-fourth of children

may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation, and

up to 38% may have no helpful physical exam findings.

The complete triad of coughing, wheezing, and

decreased or absent breath sounds is present in only

about 40% of cases. Other suggestive physical exam

findings are stridor, tachypnea, retractions, rales, and

fever. They are often misdiagnosed as croup, asthma,

pneumonia, or bronchitis. This is a diagnostic pitfall

that should be avoided. Thus, the diagnosis of foreign

body aspiration must be considered in any previously

well, child who has a history of acute onset of choking,

coughing, or wheezing, as well as any child who has a

poorly defined, chronic respiratory complaint.

Remember this general principle:

Nuts + Choking = Bronchoscopy

(regardless of radiographic results)

Roughly 85% of foreign bodies are bronchial, while

15% are laryngotracheal. Laryngotracheal foreign

bodies are more difficult to diagnose and they have a

higher mortality rate. Differential findings, clinically or

radiographically, may only be present in unilateral

bronchial foreign bodies. Differential findings are often

absent in bilateral bronchial foreign bodies or

laryngotracheal foreign bodies. Additionally, foreign

bodies may shift in position. Thus, a previously

suspicious radiographic study may be negative if it is

repeated. One cannot assume that such a patient is

now normal since a more likely explanation is that the

foreign body has moved. Avoid this pitfall.

Although appropriate radiologic studies may localize

the site of the foreign body, a significant number of

children with retained airway foreign bodies have

non-diagnostic films. Radiologic evaluation should start

with AP and lateral views of the chest and neck.

Although plain films may be interpreted as normal,

differential inflation of the affected lung, the most

common abnormality identified, may be documented by

fluoroscopy, lateral decubitus views, or an assisted

expiratory film (the examiner compresses the patient's

abdomen during expiration). Other indirect signs of an

airway foreign body include reabsorption atelectasis

beyond the site of bronchial obstruction, and the

presence of pulmonary infiltrates reflecting an

inflammatory reaction. One source (Esclamado)

reported positive findings on chest radiographs in only

42% of children with laryngotracheal (as opposed to

bronchial) foreign bodies, but a higher rate of positive

findings on lateral neck films in the same series. This

emphasizes the need to direct the examination to the

neck (ie., lateral neck view) when signs of upper airway

obstruction are present. Esophageal foreign bodies

may also cause predominantly respiratory symptoms.

Although CT scan, xeroradiography, and

ultrasonography have been advocated for foreign body

imaging, their utility is not well defined at this time.

CT scanning may be non diagnostic because of

respiratory motion (resulting in poor images) and such

patients usually require sedation which can be risky in

the presence of airway compromise. Given the high

morbidity associated with delay in the diagnosis of an

airway foreign body, and the limited sensitivity of

radiographic studies in identifying this condition, clinical

judgment must dictate whether the child should be

scheduled for diagnostic bronchoscopy in the absence

of radiographic findings.

References

Schunk JE. Foreign Body-Ingestion/Aspiration. In:

Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric

Emergency Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams

& Wilkins, 1993, pp. 210-217.

Brownstein D. Foreign Bodies of the

Gastrointestinal Tract and Airway. In: Barkin R (ed).

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical

Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book, 1992, pp.

311-314.

Hamilton AH, Carswell F, Wisheart JD. The Bristol

Children's Experience of Tracheobronchial Foreign

Bodies 1977-87. Bristol Med Chir Journal 1989;104:72.

Esclamado RM, Richardson MA. Laryngotracheal

Foreign Bodies in Children. American Journal of

Diseases in Children 1987;141:259.

The lateral neck radiograph is within normal limits.

The black dots in the upper right are pointing to a

metallic object in the holder's watch band.

These other radiographs were interpreted as

possible bilateral air trapping.

The expiratory view is fairly symmetric in this

instance. A foreign body in a bronchus is expected to

show air trapping with some hyperexpansion visible in

that lung. In the expiratory view, both lung volumes

should normally be decreased. If one side is still

expanded during expiration, this indicates air trapping

and a possible foreign body on that side.

An expiratory CXR that shows symmetry of both

lung volumes does not rule out a foreign body. Such a

CXR is often assumed to be consistent with asthma.

Although this is often true, this is occasionally a pitfall

that should be avoided by considering such a CXR to

also be consistent with a tracheal foreign body.

Examine the expiratory CXR again. It shows that both

lungs empty poorly, indicating bilateral air trapping.

This could be consistent with asthma or with a tracheal

foreign body.

The left lateral decubitus view (left side down) shows

the left lung volume to be somewhat smaller than the

right lung volume. However, one might expect the left

lung to be even smaller in the dependent position, so

perhaps it isn't as small as it should be. This suggests

some degree of air trapping on the left.

The right lateral decubitus view (right side down)

is of poor quality. The original film was very dark so

the scanned image is very grainy. This shows the right

lung to be clearly expanded even though it is

dependent. This suggests air trapping since a normal

lung should appear smaller in the dependent position.

The patient was taken to the operating room for

bronchoscopy. At bronchoscopy, about 15-20 pieces of

nut particles in the lower trachea and in both major

bronchi were found. They were somewhat difficult to

remove because of their small size. Most were

removed with grasping forceps and suction. He did well

postoperatively.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Approximately 75% of all cases of foreign body

aspiration occur in children less than 3 years of age.

Organic debris is most frequently retrieved on

bronchoscopy. Peanuts are the most common

offending agent. Unfortunately, only 6-17% of airway

foreign bodies are radio-opaque. Respiratory

symptoms may be produced by an object lodged

anywhere in the airway, from the hypopharynx to a

segmental bronchus.

Children who ingest or aspirate foreign bodies may

present in acute respiratory distress days or months

after the aspiration episode. Between 50% and 90% of

children have a suggestive history, most commonly of

an acute episode of paroxysmal cough. Other common

signs are cyanosis, choking, and dyspnea. However,

delays in presentation for care are common, and

concern about aspiration as a cause of the child's

symptoms may diminish as the primary event becomes

more distant. Only half of all children are diagnosed

correctly in the first 24 hours after an aspiration event.

An additional 30% receive the correct diagnosis in the

following week, while the remainder may have delays in

diagnosis of weeks to years. One-fourth of children

may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation, and

up to 38% may have no helpful physical exam findings.

The complete triad of coughing, wheezing, and

decreased or absent breath sounds is present in only

about 40% of cases. Other suggestive physical exam

findings are stridor, tachypnea, retractions, rales, and

fever. They are often misdiagnosed as croup, asthma,

pneumonia, or bronchitis. This is a diagnostic pitfall

that should be avoided. Thus, the diagnosis of foreign

body aspiration must be considered in any previously

well, child who has a history of acute onset of choking,

coughing, or wheezing, as well as any child who has a

poorly defined, chronic respiratory complaint.

Remember this general principle:

Nuts + Choking = Bronchoscopy

(regardless of radiographic results)

Roughly 85% of foreign bodies are bronchial, while

15% are laryngotracheal. Laryngotracheal foreign

bodies are more difficult to diagnose and they have a

higher mortality rate. Differential findings, clinically or

radiographically, may only be present in unilateral

bronchial foreign bodies. Differential findings are often

absent in bilateral bronchial foreign bodies or

laryngotracheal foreign bodies. Additionally, foreign

bodies may shift in position. Thus, a previously

suspicious radiographic study may be negative if it is

repeated. One cannot assume that such a patient is

now normal since a more likely explanation is that the

foreign body has moved. Avoid this pitfall.

Although appropriate radiologic studies may localize

the site of the foreign body, a significant number of

children with retained airway foreign bodies have

non-diagnostic films. Radiologic evaluation should start

with AP and lateral views of the chest and neck.

Although plain films may be interpreted as normal,

differential inflation of the affected lung, the most

common abnormality identified, may be documented by

fluoroscopy, lateral decubitus views, or an assisted

expiratory film (the examiner compresses the patient's

abdomen during expiration). Other indirect signs of an

airway foreign body include reabsorption atelectasis

beyond the site of bronchial obstruction, and the

presence of pulmonary infiltrates reflecting an

inflammatory reaction. One source (Esclamado)

reported positive findings on chest radiographs in only

42% of children with laryngotracheal (as opposed to

bronchial) foreign bodies, but a higher rate of positive

findings on lateral neck films in the same series. This

emphasizes the need to direct the examination to the

neck (ie., lateral neck view) when signs of upper airway

obstruction are present. Esophageal foreign bodies

may also cause predominantly respiratory symptoms.

Although CT scan, xeroradiography, and

ultrasonography have been advocated for foreign body

imaging, their utility is not well defined at this time.

CT scanning may be non diagnostic because of

respiratory motion (resulting in poor images) and such

patients usually require sedation which can be risky in

the presence of airway compromise. Given the high

morbidity associated with delay in the diagnosis of an

airway foreign body, and the limited sensitivity of

radiographic studies in identifying this condition, clinical

judgment must dictate whether the child should be

scheduled for diagnostic bronchoscopy in the absence

of radiographic findings.

References

Schunk JE. Foreign Body-Ingestion/Aspiration. In:

Fleisher GR, Ludwig S (eds). Textbook of Pediatric

Emergency Medicine, third edition. Baltimore, Williams

& Wilkins, 1993, pp. 210-217.

Brownstein D. Foreign Bodies of the

Gastrointestinal Tract and Airway. In: Barkin R (ed).

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical

Practice. Chicago, Mosby Year Book, 1992, pp.

311-314.

Hamilton AH, Carswell F, Wisheart JD. The Bristol

Children's Experience of Tracheobronchial Foreign

Bodies 1977-87. Bristol Med Chir Journal 1989;104:72.

Esclamado RM, Richardson MA. Laryngotracheal

Foreign Bodies in Children. American Journal of

Diseases in Children 1987;141:259.