Abdominal Pain with a Negative Abdominal Examination

Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Volume 1, Case 3

Loren G. Yamamoto, MD, MPH

Kapiolani Medical Center For Women And Children

University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine

A 6 year old male presents to the ED with a chief

complaint of fever and stomach pain since last night. It

is now 11:00 a.m. The temperature was not measured

at home but he felt warm. He was given an unspecified

dose of acetaminophen at 4:00 a.m. There was no

history of nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. His last bowel

movement was three days ago. He pointed to his

epigastrium as the location of most of his pain.

Exam: VS T38 (tympanic), P136, R24, BP 113/61.

He was noted to be small for age (19.3 kg), alert,

active, in no distress. He did not appear to be

uncomfortable at all. HEENT exam was unremarkable.

Neck supple without adenopathy. Heart regular without

murmurs. Lungs clear. Abdominal exam was positive

for mild tenderness in the epigastrium. Bowel sounds

were active. No tenderness in the right lower quadrant.

No rebound tenderness. No hepatosplenomegaly or

masses were appreciated. Testes were normal. A

rectal exam revealed normal sphincter tone, no

masses, and no right lower quadrant tenderness. The

stool tested negative for occult blood. An abdominal

series was ordered. An AP view of the chest was also

ordered as part of the abdominal series.

View abdominal series: Flat (Supine) view

View abdominal series: Upright view

View abdominal series: Upright view

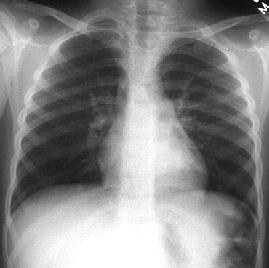

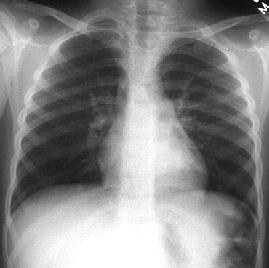

View AP chest:

View AP chest:

The radiographs were interpreted as showing

non-specific findings. Because the cause of the

abdominal pain was suspected to be constipation, the

patient was given an enema. Following this, he passed

a large amount of stool and felt much better. His

abdominal exam continued to be benign. He was

discharged from the ED. Overnight, the patient

continued to experience fever at home and some

abdominal pain though the degree of abdominal pain

was improved. A review of his radiographs the

following morning revealed an alternative diagnosis for

his symptoms.

Review his abdominal series again above.

If you are still unable to identify the radiographic

diagnosis, review the focused enlarged view of the

lesion.

The radiographs were interpreted as showing

non-specific findings. Because the cause of the

abdominal pain was suspected to be constipation, the

patient was given an enema. Following this, he passed

a large amount of stool and felt much better. His

abdominal exam continued to be benign. He was

discharged from the ED. Overnight, the patient

continued to experience fever at home and some

abdominal pain though the degree of abdominal pain

was improved. A review of his radiographs the

following morning revealed an alternative diagnosis for

his symptoms.

Review his abdominal series again above.

If you are still unable to identify the radiographic

diagnosis, review the focused enlarged view of the

lesion.

This view provides a focused view of the lesion.

Note the triangular density superimposed on the heart.

The flat (supine) view shows this best (see below).

It is located at the very top of the flat (supine view).

This view provides a focused view of the lesion.

Note the triangular density superimposed on the heart.

The flat (supine) view shows this best (see below).

It is located at the very top of the flat (supine view).

This represents a pulmonary infiltrate in the medial

aspect of the left lower lobe. The top of it is cut off in

the flat (supine) view of the abdomen. It is almost

impossible to appreciate this density on the upright view

because most of it is cut off. The chest radiograph was

taken using a different degree of penetration to view the

lungs better. Because of this, it is even more difficult to

appreciate the infiltrate behind the heart. Upon close

inspection, you should be able to appreciate the

triangular density superimposed on the heart on the

chest radiograph view. A lateral view of the chest was

not taken in this case since the chest view was part of

an abdominal series that was ordered.

The patient was placed on antibiotics and his fever

promptly improved by the next day. His abdominal pain

and his other symptoms gradually improved.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Pneumonia is a known cause of abdominal pain.

This diagnosis is often not considered because the

abdominal pain is the chief complaint. The pain can be

very severe at times. This can easily mislead a

clinician to limit the area of investigation to the

abdomen. This pitfall should be avoided. Causes of

abdominal pain that are not related to the abdomen

include pneumonia, pneumothorax,

pneumomediastinum, pericarditis, zoster, vertebral

conditions (eg., osteomyelitis, discitis), diabetic

ketoacidosis, etc. Adult conditions that are less likely

but still possible in children include myocardial ischemia

and aortic dissection.

Pulmonary conditions should be considered in

patients with respiratory symptoms, tachypnea, or a

borderline oxygen saturation. Documentation of these

findings should be routine in patients with abdominal

pain. The history should include the presence of and

the severity of respiratory symptoms. The vital signs

should include a respiratory rate and a pulse oximetry

reading. The examination should include notes

describing the presence or absence of any observed

tachypnea, the degree of coughing observed, the

characteristics of the cough (eg., moist, productive,

bronchospastic, dry, etc.), and the standard pulmonary

auscultation and percussion findings. If any of these

findings suggest the possibility of pneumonia, PA and

lateral chest radiographs should be ordered, or

alternatively, treatment prescribed for a clinical

diagnosis of a respiratory infection.

Although the likelihood of aortic dissection is low

(especially in children), this condition is associated with

a substantial likelihood of death which may be

preventable if the diagnosis is suspected early. While

aortic contrast studies by CT or aortography are not

routine, one suggestion has been to document the

presence and character of peripheral pulses in all

patients presenting with abdominal pain.

Although the appendix is often the focus of clinical

examination in patients with abdominal pain, there are

other serious causes of abdominal pain that should be

considered as well, such as intussusception, volvulus,

pancreatitis, ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, acute

cholecystitis, etc.

The radiographic findings in intussusception may

range from normal to various indirect signs of

intussusception (refer to Case 2 which describes the

radiographic findings in intussusception). A volvulus

is usually associated with a true bowel obstruction, but

the presentation clinically and radiographically can

occasionally be subtle.

Ovarian torsion may be a difficult diagnosis to make.

Even the use of color flow doppler ultrasound used to

assess blood flow to the ovaries is not able to totally

rule out this diagnosis since, early in its presentation,

some blood flow may still be preserved.

Testicular torsion is usually suspected on clinical

grounds, but occasionally the testes are not examined

in some patients because their pants and underwear (or

diapers) are not removed. Younger patients may fail to

point to their testes as the location of the pain. Some

may complain of non-specific abdominal pain because

of failure to appreciate the source of the pain, or

because of modesty.

In summary, the causes of abdominal pain are

extensive. In the acute care setting, it is most important

to rule out diagnoses that must be made early to result

in the best possible outcome for the patient. Some of

these diagnoses have been mentioned, but there are

others.

This represents a pulmonary infiltrate in the medial

aspect of the left lower lobe. The top of it is cut off in

the flat (supine) view of the abdomen. It is almost

impossible to appreciate this density on the upright view

because most of it is cut off. The chest radiograph was

taken using a different degree of penetration to view the

lungs better. Because of this, it is even more difficult to

appreciate the infiltrate behind the heart. Upon close

inspection, you should be able to appreciate the

triangular density superimposed on the heart on the

chest radiograph view. A lateral view of the chest was

not taken in this case since the chest view was part of

an abdominal series that was ordered.

The patient was placed on antibiotics and his fever

promptly improved by the next day. His abdominal pain

and his other symptoms gradually improved.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Pneumonia is a known cause of abdominal pain.

This diagnosis is often not considered because the

abdominal pain is the chief complaint. The pain can be

very severe at times. This can easily mislead a

clinician to limit the area of investigation to the

abdomen. This pitfall should be avoided. Causes of

abdominal pain that are not related to the abdomen

include pneumonia, pneumothorax,

pneumomediastinum, pericarditis, zoster, vertebral

conditions (eg., osteomyelitis, discitis), diabetic

ketoacidosis, etc. Adult conditions that are less likely

but still possible in children include myocardial ischemia

and aortic dissection.

Pulmonary conditions should be considered in

patients with respiratory symptoms, tachypnea, or a

borderline oxygen saturation. Documentation of these

findings should be routine in patients with abdominal

pain. The history should include the presence of and

the severity of respiratory symptoms. The vital signs

should include a respiratory rate and a pulse oximetry

reading. The examination should include notes

describing the presence or absence of any observed

tachypnea, the degree of coughing observed, the

characteristics of the cough (eg., moist, productive,

bronchospastic, dry, etc.), and the standard pulmonary

auscultation and percussion findings. If any of these

findings suggest the possibility of pneumonia, PA and

lateral chest radiographs should be ordered, or

alternatively, treatment prescribed for a clinical

diagnosis of a respiratory infection.

Although the likelihood of aortic dissection is low

(especially in children), this condition is associated with

a substantial likelihood of death which may be

preventable if the diagnosis is suspected early. While

aortic contrast studies by CT or aortography are not

routine, one suggestion has been to document the

presence and character of peripheral pulses in all

patients presenting with abdominal pain.

Although the appendix is often the focus of clinical

examination in patients with abdominal pain, there are

other serious causes of abdominal pain that should be

considered as well, such as intussusception, volvulus,

pancreatitis, ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, acute

cholecystitis, etc.

The radiographic findings in intussusception may

range from normal to various indirect signs of

intussusception (refer to Case 2 which describes the

radiographic findings in intussusception). A volvulus

is usually associated with a true bowel obstruction, but

the presentation clinically and radiographically can

occasionally be subtle.

Ovarian torsion may be a difficult diagnosis to make.

Even the use of color flow doppler ultrasound used to

assess blood flow to the ovaries is not able to totally

rule out this diagnosis since, early in its presentation,

some blood flow may still be preserved.

Testicular torsion is usually suspected on clinical

grounds, but occasionally the testes are not examined

in some patients because their pants and underwear (or

diapers) are not removed. Younger patients may fail to

point to their testes as the location of the pain. Some

may complain of non-specific abdominal pain because

of failure to appreciate the source of the pain, or

because of modesty.

In summary, the causes of abdominal pain are

extensive. In the acute care setting, it is most important

to rule out diagnoses that must be made early to result

in the best possible outcome for the patient. Some of

these diagnoses have been mentioned, but there are

others.

Return to Radiology Cases In Ped Emerg Med Case Selection Page

Return to Univ. Hawaii Dept. Pediatrics Home Page

View abdominal series: Upright view

View abdominal series: Upright view

View AP chest:

View AP chest:

The radiographs were interpreted as showing

non-specific findings. Because the cause of the

abdominal pain was suspected to be constipation, the

patient was given an enema. Following this, he passed

a large amount of stool and felt much better. His

abdominal exam continued to be benign. He was

discharged from the ED. Overnight, the patient

continued to experience fever at home and some

abdominal pain though the degree of abdominal pain

was improved. A review of his radiographs the

following morning revealed an alternative diagnosis for

his symptoms.

Review his abdominal series again above.

If you are still unable to identify the radiographic

diagnosis, review the focused enlarged view of the

lesion.

The radiographs were interpreted as showing

non-specific findings. Because the cause of the

abdominal pain was suspected to be constipation, the

patient was given an enema. Following this, he passed

a large amount of stool and felt much better. His

abdominal exam continued to be benign. He was

discharged from the ED. Overnight, the patient

continued to experience fever at home and some

abdominal pain though the degree of abdominal pain

was improved. A review of his radiographs the

following morning revealed an alternative diagnosis for

his symptoms.

Review his abdominal series again above.

If you are still unable to identify the radiographic

diagnosis, review the focused enlarged view of the

lesion.

This view provides a focused view of the lesion.

Note the triangular density superimposed on the heart.

The flat (supine) view shows this best (see below).

It is located at the very top of the flat (supine view).

This view provides a focused view of the lesion.

Note the triangular density superimposed on the heart.

The flat (supine) view shows this best (see below).

It is located at the very top of the flat (supine view).

This represents a pulmonary infiltrate in the medial

aspect of the left lower lobe. The top of it is cut off in

the flat (supine) view of the abdomen. It is almost

impossible to appreciate this density on the upright view

because most of it is cut off. The chest radiograph was

taken using a different degree of penetration to view the

lungs better. Because of this, it is even more difficult to

appreciate the infiltrate behind the heart. Upon close

inspection, you should be able to appreciate the

triangular density superimposed on the heart on the

chest radiograph view. A lateral view of the chest was

not taken in this case since the chest view was part of

an abdominal series that was ordered.

The patient was placed on antibiotics and his fever

promptly improved by the next day. His abdominal pain

and his other symptoms gradually improved.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Pneumonia is a known cause of abdominal pain.

This diagnosis is often not considered because the

abdominal pain is the chief complaint. The pain can be

very severe at times. This can easily mislead a

clinician to limit the area of investigation to the

abdomen. This pitfall should be avoided. Causes of

abdominal pain that are not related to the abdomen

include pneumonia, pneumothorax,

pneumomediastinum, pericarditis, zoster, vertebral

conditions (eg., osteomyelitis, discitis), diabetic

ketoacidosis, etc. Adult conditions that are less likely

but still possible in children include myocardial ischemia

and aortic dissection.

Pulmonary conditions should be considered in

patients with respiratory symptoms, tachypnea, or a

borderline oxygen saturation. Documentation of these

findings should be routine in patients with abdominal

pain. The history should include the presence of and

the severity of respiratory symptoms. The vital signs

should include a respiratory rate and a pulse oximetry

reading. The examination should include notes

describing the presence or absence of any observed

tachypnea, the degree of coughing observed, the

characteristics of the cough (eg., moist, productive,

bronchospastic, dry, etc.), and the standard pulmonary

auscultation and percussion findings. If any of these

findings suggest the possibility of pneumonia, PA and

lateral chest radiographs should be ordered, or

alternatively, treatment prescribed for a clinical

diagnosis of a respiratory infection.

Although the likelihood of aortic dissection is low

(especially in children), this condition is associated with

a substantial likelihood of death which may be

preventable if the diagnosis is suspected early. While

aortic contrast studies by CT or aortography are not

routine, one suggestion has been to document the

presence and character of peripheral pulses in all

patients presenting with abdominal pain.

Although the appendix is often the focus of clinical

examination in patients with abdominal pain, there are

other serious causes of abdominal pain that should be

considered as well, such as intussusception, volvulus,

pancreatitis, ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, acute

cholecystitis, etc.

The radiographic findings in intussusception may

range from normal to various indirect signs of

intussusception (refer to Case 2 which describes the

radiographic findings in intussusception). A volvulus

is usually associated with a true bowel obstruction, but

the presentation clinically and radiographically can

occasionally be subtle.

Ovarian torsion may be a difficult diagnosis to make.

Even the use of color flow doppler ultrasound used to

assess blood flow to the ovaries is not able to totally

rule out this diagnosis since, early in its presentation,

some blood flow may still be preserved.

Testicular torsion is usually suspected on clinical

grounds, but occasionally the testes are not examined

in some patients because their pants and underwear (or

diapers) are not removed. Younger patients may fail to

point to their testes as the location of the pain. Some

may complain of non-specific abdominal pain because

of failure to appreciate the source of the pain, or

because of modesty.

In summary, the causes of abdominal pain are

extensive. In the acute care setting, it is most important

to rule out diagnoses that must be made early to result

in the best possible outcome for the patient. Some of

these diagnoses have been mentioned, but there are

others.

This represents a pulmonary infiltrate in the medial

aspect of the left lower lobe. The top of it is cut off in

the flat (supine) view of the abdomen. It is almost

impossible to appreciate this density on the upright view

because most of it is cut off. The chest radiograph was

taken using a different degree of penetration to view the

lungs better. Because of this, it is even more difficult to

appreciate the infiltrate behind the heart. Upon close

inspection, you should be able to appreciate the

triangular density superimposed on the heart on the

chest radiograph view. A lateral view of the chest was

not taken in this case since the chest view was part of

an abdominal series that was ordered.

The patient was placed on antibiotics and his fever

promptly improved by the next day. His abdominal pain

and his other symptoms gradually improved.

Discussion and Teaching Points:

Pneumonia is a known cause of abdominal pain.

This diagnosis is often not considered because the

abdominal pain is the chief complaint. The pain can be

very severe at times. This can easily mislead a

clinician to limit the area of investigation to the

abdomen. This pitfall should be avoided. Causes of

abdominal pain that are not related to the abdomen

include pneumonia, pneumothorax,

pneumomediastinum, pericarditis, zoster, vertebral

conditions (eg., osteomyelitis, discitis), diabetic

ketoacidosis, etc. Adult conditions that are less likely

but still possible in children include myocardial ischemia

and aortic dissection.

Pulmonary conditions should be considered in

patients with respiratory symptoms, tachypnea, or a

borderline oxygen saturation. Documentation of these

findings should be routine in patients with abdominal

pain. The history should include the presence of and

the severity of respiratory symptoms. The vital signs

should include a respiratory rate and a pulse oximetry

reading. The examination should include notes

describing the presence or absence of any observed

tachypnea, the degree of coughing observed, the

characteristics of the cough (eg., moist, productive,

bronchospastic, dry, etc.), and the standard pulmonary

auscultation and percussion findings. If any of these

findings suggest the possibility of pneumonia, PA and

lateral chest radiographs should be ordered, or

alternatively, treatment prescribed for a clinical

diagnosis of a respiratory infection.

Although the likelihood of aortic dissection is low

(especially in children), this condition is associated with

a substantial likelihood of death which may be

preventable if the diagnosis is suspected early. While

aortic contrast studies by CT or aortography are not

routine, one suggestion has been to document the

presence and character of peripheral pulses in all

patients presenting with abdominal pain.

Although the appendix is often the focus of clinical

examination in patients with abdominal pain, there are

other serious causes of abdominal pain that should be

considered as well, such as intussusception, volvulus,

pancreatitis, ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, acute

cholecystitis, etc.

The radiographic findings in intussusception may

range from normal to various indirect signs of

intussusception (refer to Case 2 which describes the

radiographic findings in intussusception). A volvulus

is usually associated with a true bowel obstruction, but

the presentation clinically and radiographically can

occasionally be subtle.

Ovarian torsion may be a difficult diagnosis to make.

Even the use of color flow doppler ultrasound used to

assess blood flow to the ovaries is not able to totally

rule out this diagnosis since, early in its presentation,

some blood flow may still be preserved.

Testicular torsion is usually suspected on clinical

grounds, but occasionally the testes are not examined

in some patients because their pants and underwear (or

diapers) are not removed. Younger patients may fail to

point to their testes as the location of the pain. Some

may complain of non-specific abdominal pain because

of failure to appreciate the source of the pain, or

because of modesty.

In summary, the causes of abdominal pain are

extensive. In the acute care setting, it is most important

to rule out diagnoses that must be made early to result

in the best possible outcome for the patient. Some of

these diagnoses have been mentioned, but there are

others.