Figure 1. Operant conditioning and parent management therapy for ODD and CD (2,3,7,9,12)

A 10 year old boy is brought to the clinic by his mother for a well-child check. When asked about how he is doing, his mother says she is concerned about his behavior. He is disobedient and refuses to help around the house when asked. Over the past year, they have been getting into more verbal arguments, but he has never been physically violent. He has a history of anger, with many tantrums occurring since he was a toddler. He struggles with reading in school, and his teachers say that he is unable to sit still during class or pay attention for long periods of time. Mother has received several calls from the school because he shouted and cussed at other students. When asking the boy what he thinks about his motherís concerns, he shrugs and says he thinks she is unreasonable. He says he doesnít care about how he does in school because school is stupid and his classmates are all annoying. You suspect he could have oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), so you talk with his mother about what ODD is and possible behavioral interventions to be done in the home and resources his school may be able to provide. They do not return for follow-up.

Five years pass, and you are surprised to see the boy and his mother walk into the office. The mother looks distraught, saying her sonís behavior is escalating and she is at a loss for what to do. His behavior became significantly worse after the divorce of his parents. Since then, his school performance drastically dropped because he often skips school and he received multiple suspensions for bullying and getting into physical fights. He also stays out late at night and is sometimes gone for several days on end. She has been called into the police station several times because he was caught trying to steal small electronics items. When speaking with the boy alone, he tells you he isnít concerned about how heís doing in school and doesnít go home much because his mother is sad and cries all the time, and every time they see each other they get into arguments. When asked to describe his mood he replies "not great", but getting into fights and stealing helps him feel a little better. When asking if he can talk to anyone about how heís feeling, he says he doesnít have any friends because he just doesnít get along with people his age. Concerned, you ask his mother to fill out a behavioral checklist and ask if she could give copies to his teachers to fill out too. Meanwhile, you start to think of possible behavioral interventions that can help your patient and his family.

In childhood and adolescence, rebellious behaviors and disrespect towards authority can be developmentally normal. These behaviors alone are not sufficient reason to warrant medical treatment (1). In externalizing disorders such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), defiant or disrespectful behaviors are present in increased severity, cause functional impairment, and persist across a childís development (2). These conditions account for about one-third to one-half of child and adolescent psychiatry referrals and are associated with high rates of morbidity, other psychiatric comorbidities, and high rates of public expenditure in the justice system (2).

ODD is described as a pattern of angry or irritable mood and developmentally inappropriate argumentative or defiant behaviors (2,3,4,5). It primarily involves the inability to regulate oneís emotions and control oneís behavior (2,3). ODD can manifest in several ways: refusal to follow directions or testing limits of authority figures, unwillingness to compromise with others, arguing, and denying blame (5). Oppositional behaviors are more common than aggressive behaviors in children, and they usually peak around mid-childhood (6).

Conduct disorder (CD) is a persistent pattern of behavior that violates the rights of others and age-appropriate social norms (2,5,7). This includes physical aggression towards people or animals, property destruction, deceitfulness, or theft, and serious rule violations such as skipping school, staying out late, or running away from home (4,5).

ODD and CD are related conditions that seem similar, but there are several key differences. They are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Differences between ODD and CD (4,5,6,8)

| Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) | Conduct disorder (CD) |

| -Characterized by: angry/irritable mood, argumentative or defiant behavior, vindictiveness -Verbal, overt, and reactive aggression is more common -Behaviors persist for 6 months or longer -Actions tend to be less severe than CD -Risk factor for CD | -Characterized by: aggression towards people or animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness or theft, serious violation of rules -Physical, covert, and proactive aggression is displayed -Behaviors persist for 12 months or longer -Increased rates of conflict with schools and judicial systems -Rare after 16 years old |

ODD is present in about 2% to 11% of children and adolescents (3,5). The average age of onset of ODD is 6 years old (2,6). Rates of ODD diagnoses increase from preschool to high school, then decrease in college-age adolescents (2,5). It is slightly more common in boys, especially during the preadolescent years (2,3,6). ODD tends to be disproportionately prevalent in lower socioeconomic status (SES) populations (5).

CD is present in similar proportions to ODD, in around 2% to 10% of children and adolescents (5,7). The average age of onset of CD is 11 years old in boys and 15 years old in girls (2,8). Rates of CD tend to increase from middle childhood to adolescence, with the most severe behaviors occurring during adolescence (5). CD is significantly more common in boys, with this difference being pronounced in pre-adolescence as well (2,6,7). There may also be differences in behaviors most typically demonstrated according to gender. Boys tend to display more physical aggression and property destruction, such as getting into fights, stealing, and vandalizing property. Girls are more likely to violate rules (be truant, run away from home), lie, and misuse substances (9). Rates of CD are higher in children in juvenile detention, and children with early-onset CD account for a disproportionate amount of crime (2). CD is also disproportionately seen in lower SES populations (5). ODD and CD are commonly co-existing conditions, with both seen in about 96% of clinical patients and in 60% of the general population with behaviors consistent with ODD or CD (8). The etiology of ODD and CD is multifactorial, involving genetic, environmental, physiological, and psychosocial factors.

Both ODD and CD are moderately heritable with substantial genetic overlap with each other (3,6). It is thought that several genes involved in noradrenergic, dopaminergic, and serotonergic neurotransmission may be affected. These include the monoamine oxidase A gene (MAO-A), serotonin transporter gene, and dopamine receptor genes (2,6,10). In addition, lower levels of 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) may be implicated in the pathogenesis of ODD and CD (2,6,7). In CD, these genetic influences may be up to 50% responsible for acquisition of the condition, and they account for about 40% of variations in antisocial behavior (2). The risk of developing CD is higher for children whose parents have antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), alcohol use disorder (AUD), mood disorders, or schizophrenia (5). This risk is also increased in children whose siblings have CD (5).

Environmental risk factors play a significant role in the development of ODD and CD. Harsh, inconsistent parenting, and child maltreatment such as neglect and physical abuse (2,3,6,7) are heavily implicated in the pathogenesis of ODD and CD. Children with harsh parents may model those behaviors, learning they are acceptable means of interacting with others (2). There is also a high prevalence of sexual abuse among girls with CD (6). Lack of positive attention in the household may increase the likelihood of a child using oppositional behaviors to receive attention. Creating a feedback cycle that worsens behaviors as the negative attention increases (9,10). Fragmentation of the household including strained marital relationships, poor family structure, stress, and criminality also increase the risk of developing ODD or CD (2,5,6,7). Factors involving the mother such as maternal depression (2,5) and use of alcohol, nicotine, or cocaine (2,6,7) during pregnancy also increases the risk of a child developing ODD or CD. The amount of consumption matters as well; greater alcohol consumption during pregnancy has been linked with higher risk for CD (2). Lead exposure may also be a risk factor for CD and problems sustaining attention (2,6). Children living in crowded households are at higher risk for ODD and CD (2,5,7). Gene-environment interactions are also implicated in ODD and CD. For example, studies have shown children with low activity of the MAO-A gene who are exposed to abuse are more likely to report conduct issues and hostility when they are older (2,3).

Physiological factors have also been found to be linked with ODD and CD. Imaging studies have found that areas of the brain such as the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, insula, and cingulate cortices are shrunken in people with ODD and CD (2,3,6,8). Impaired function of the amygdala causes reduced sensitivity to fear. This reduces the effects of punishment and aversive cues, making it more difficult to learn to stop inappropriate behaviors (2,10). There is also a theory called the reward processing theory which states that people with antisocial behaviors are constantly in an unpleasant internal state, and to maintain a neutral state, they engage in risk-taking and aggression as sensation-seeking behaviors (2). Deficits in the orbitofrontal cortex and cingulate cortices may impair executive cognitive function, making it harder to learn from motivational factors such as punishments and rewards (10). This may also be responsible for impaired recognition of othersí emotions, especially anger, in people with ODD and CD. Children with ODD and CD have lower baseline cortisol levels than the general population, indicating decreased sensitivity to stress (2,3,8). People with CD were found to have a lower resting heart rate, which may be a predictor of violent behavior independent of other social risk factors (2,6). High testosterone levels may be implicated in aggression in ODD and CD, but this may only have substantial effect in post-pubertal children (2).

There are several psychosocial risk factors involved in the pathogenesis of ODD and CD. Infants who are irritable, impulsive, easily frustrated, emotionally volatile, or unable to adapt to new circumstances may be at increased risk (3,6). Peer rejection and associated deviant peer groups may play a large role (2, 3). In aggressive children, this may occur earlier in life due to the inability to interpret social events and recognize social cues, reflecting deficits in social information processing and problem-solving (2,6,10). Poverty and community violence increase the risk for development of ODD and CD (2, 3, 7).

Table 2. Summary of the multiple etiologies of ODD and CD and their interconnections (2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10)

| Physiologic | Genetic | Genetic + Environmental & Psychosocial | Environmental & Psychosocial |

| -Low cortisol (reduced sensitivity to stress) -Smaller amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, insula is associated with reduced sensitivity to fear and motivation, deficits in executive functioning, decreased ability to recognize emotions -High testosterone (postpubescent) | -Genes for neurotransmission (noradrenergic, serotonergic, dopaminergic) -Higher risk if parents have antisocial personality disorder, ADHD, CD, and alcohol use disorder -Higher risk if siblings have CD | -Low MAO-A activity and exposure to childhood abuse increases risk for ODD and CD -Maternal depression, substance use during pregnancy | -Harsh, inconsistent parenting -Maltreatment (neglect, physical, or sexual abuse) -Strained family relations and family structure -Irritability, impulsivity, high emotional reactivity, inability to adapt to new situations in infants -Peer rejection, association with deviant peer groups -Difficulty interpreting social cues and intentions of others -Poverty, neighborhood violence |

There are many comorbidities associated with ODD and CD. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most commonly reported comorbidity in both ODD and CD (1,2,3,5,11). Co-occurrence of ODD or CD with ADHD increases symptom severity and risk for early onset of antisocial behaviors (2,6) and substance use disorder (SUD) in adulthood (6,8). The association between ODD and ADHD may be due to genetic effects (3).

Psychiatric conditions such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders (depression, bipolar disorder), SUD, and schizophrenia are also commonly seen in children and teens with ODD and CD (2,5). In children with ODD, a dominant prevalence of an angry or irritated mood predicts increased rates of anxiety and depression (5). Females with CD were found to have higher instances of internalizing disorders (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)), SUD, and borderline personality disorder (BPD) than males, but males have higher rates of ADHD than females (9). Learning disabilities and language disorders are also commonly seen in children with ODD and CD (2).

Assessment

It can be challenging to assess for ODD and CD in the clinical setting. Diagnostic criteria for ODD and CD are defined by the DSM-V (criteria shown in Tables 3 and 4). Most often, symptoms are rarely apparent during the visit because behaviors tend to occur most commonly in the home setting and towards individuals the child knows well (5). Information should be gathered from multiple parties: parents, the child (if older), teachers, and other adults who have known the child for an extended period of time (2,6,12). It is important to form therapeutic alliances with both the child and family and to consider possible cultural barriers during the clinical visit (12). For CD, if the child is older, self-reports can be reliable if the clinical interview is conducted in a judgment-free zone and in an honest manner (2). Behavioral checklists that are used to screen for ADHD like the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) and Vanderbilt scales can be filled out by both teachers and parents with additional questions to also assess for signs of both ODD and CD (5,6). There are also assessments that measure the extent of oppositional or aggressive behaviors and ones that look at risk factors in parenting and the home environment (6).

Table 3. DSM-V criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) (4)

| A pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behavior, or vindictiveness lasting at least 6 months as evidenced by at least four symptoms of the following categories, and exhibited during interaction with at least one individual who is not a sibling:

A. Angry/irritable mood 1. Often loses temper 2. Often touchy or easily annoyed 3. Often angry and resentful B. Argumentative or defiant behavior 1. Often argues with authority figures (for children and adolescents, with adults) 2. Often actively defies or refuses to comply with requests from authority figures or with rules 3. Often deliberately annoys others 4. Often blames others for their mistakes or misbehavior C. Vindictiveness 1. Has been spiteful or vindictive at least twice in past 6 months Specifications:

|

| Disturbances in behavior are associated with distress to the individual or others in their immediate social context or negatively impacts social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Behaviors are not due to psychosis, substance use, or depressive or bipolar disorders. Criteria is also not met for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). |

| Specify current severity:

-Mild: symptoms seen in only one setting -Moderate: some symptoms in at least two settings -Severe: some symptoms in three or more settings |

Table 4. DSM-V criteria for Conduct Disorder (CD) (4)

| A repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or age-appropriate social norms or rules are violated with three or more of the following in the past 12 months, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 months:

A. Aggression to people or animals 1. Often bullies, threatens, or intimidates others 2. Often initiates physical fights 3. Has used a weapon that can cause serious physical harm to others (bat, brick, broken bottle, knife, gun) 4. Has been physically cruel to people 5. Has been physically cruel to animals 6. Has stolen while confronting a victim (mugging, purse snatching, extortion, armed robbery) 7. Has forced someone into sexual activity B. Destruction of property 1. Has deliberately engaged in fire setting with the intention of causing serious damage 2. Has deliberately destroyed othersí property (other than fire setting) C. Deceitfulness or theft 1. Has broken into someoneís house, building, or car 2. Often lies to obtain goods or favors or to avoid obligations (cons others) 3. Has stolen items of nontrivial value without confronting a victim (shoplifting but without breaking and entering; forgery) D Serious violations of rules 1. Often stays out at night despite parental prohibitions, beginning before age 13 years 2. Has run away from home overnight as least twice while living in parental or parental surrogate home (or once without returning for a lengthy period) 3. Is often truant from school, beginning before age 13 years |

| Disturbances in behavior causes clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning |

| If individual is 18 years or older, criteria are not met for antisocial personality disorder |

| Specify whether:

-Childhood onset: at least one symptom prior to age 10 -Adolescent-onset: no symptoms prior to age 10 -Unspecified-onset: unable to determine onset of symptoms |

| Limited prosocial emotions: individual must have displayed at least two of the following within 12 months and in multiple relationships and settings (needs to be reported from multiple sources who have known individual for extended periods of time: parents, teachers, coworkers, extended family members, peers):

-Lack of remorse or guilt: does not feel bad or guilty when they do something wrong (besides remorse when facing punishment) and shows lack of concern about negative consequences of their actions. E.g., not remorseful after hurting someone, does not care about consequences of breaking rules -Callous (lack of empathy): disregards and is unconcerned about othersí feelings, cold and uncaring; appears more concerned about effects of their actions on themselves than on others, even when resulting in substantial harm -Unconcerned about performance: does not show concern about poor or problematic performance at school, work, etc.; does not put forth effort to perform well even when expectations are clear and typically blames others for the poor performance -Shallow or deficient affect: does not express feelings or show emotions to others except in ways that seem shallow, insincere, or superficial or when emotional expressions are used for gain (manipulation, intimidation) |

| Specify current severity:

-Mild: no or few conduct problems in excess of those needed for diagnosis + problems cause relatively mild harm to others. E.g., lying, truancy, staying out after dark without permission, other rule breaking -Moderate: number of conduct problems and effects on others are intermediate. E.g., stealing without confronting a victim, vandalism -Severe: many conduct problems in excess of those needed for diagnosis or problems cause considerable harm to others. E.g., forced sex, physical cruelty, use of weapon stealing while confronting a victim, breaking and entering |

The clinical assessment should involve looking for signs of comorbid conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, or depression or other conditions that may exhibit similar behaviors such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (2,3,6). It is also important to identify risk factors that could be causing oppositional or aggressive behaviors such as bullying and poor school performance (3). All children need to be given opportunities to undergo academic assessments (intelligence testing, adaptive functioning tests, learning assessments) to look for co-occurring learning disabilities, intellectual disability, hearing disorders, or language impairments (2,3,6). This could help them access more structured support or accommodations at school.

Management

The management of ODD and CD is multimodal, involving the patient and their family, school, and community (2,3,7,11). Effective interventions are performed at regular intervals, are long-term, and involve collaboration with multiple disciplines (2). It is also very important to address and treat any comorbid conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, mood disorders, and learning disorders (2,3,5,11,12). Ideally, primary and secondary prevention would be initiated when at-risk patients are around preschool-age (2). However, that may not always be possible.

There are several modalities of behavioral management: parent management training, individual therapy (cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)), family therapy, and school-based interventions. Table 5 describes the specifics of each of these therapies. It is very important for parents/guardians to communicate with their child throughout these treatments, clearly explaining the reasons for certain actions (i.e., going to appointments, setting time limits to certain activities) (11).

Table 5. Modalities of management for ODD and CD in children and adolescents (2,3,5,6,7,11,12)

| Modality | Description |

| Parent management training | -Focuses on identifying problem behaviors in children and problems with parental management of those behaviors -Uses positive reinforcement to encourage desired or prosocial behaviors |

| Individual therapy (CBT) | -Anger management -Problem-solving skills, perspective-taking |

| Family therapy | -Identifies factors in the home environment, such as family relationships, that may be contributing to problem behaviors |

| School-based interventions | -Teacher education on how to improve classroom behaviors, de-escalate oppositional or aggressive behaviors, and encourage adherence to rules in classroom -Aims to improve school performance, peer relationships, and problem-solving skills |

| Pharmacotherapy | -Stimulants (methylphenidate) -Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (atomoxetine) -Alpha-agonists (clonidine, guanfacine) -For aggression: risperidone, lithium, valproate |

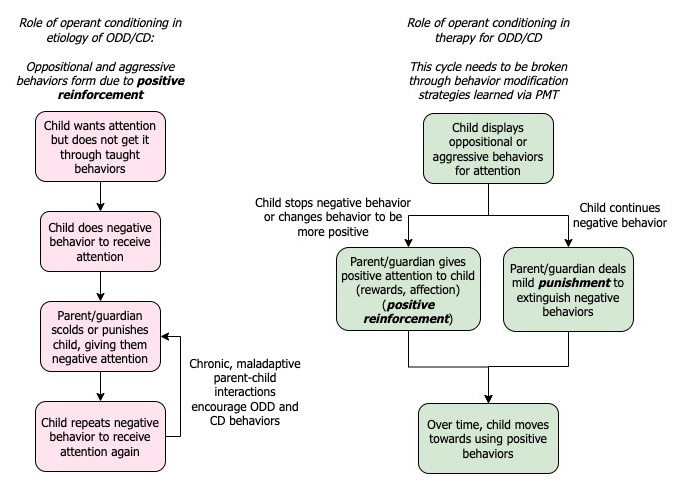

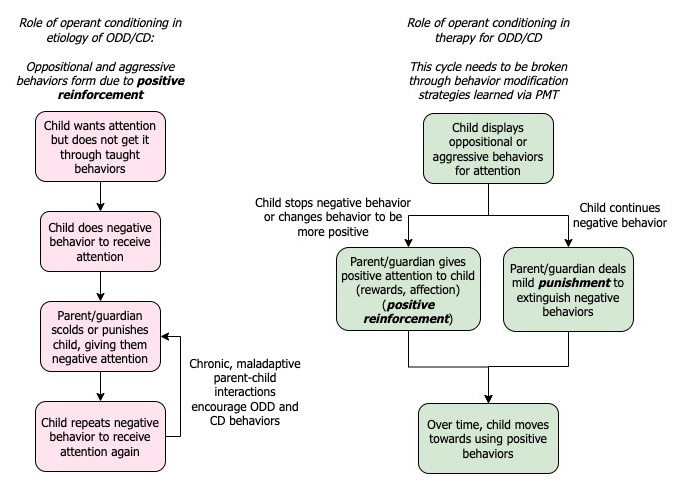

The first-line intervention, especially for school-age children, is parent management therapy (PMT) (3,6,11,12). PMT is based on operant conditioning, focused on reducing problematic or undesired behaviors and encouraging prosocial or desired ones (3,9,11,12). Parents and caregivers are the main focus of this intervention. The goal of PMT is to decrease or eliminate oppositional or aggressive behaviors. Parents or caregivers are taught how to identify behaviors that are problematic and encouraged to use consistent, positive, warm interactions (positive reinforcement) while decreasing harsh discipline practices (2,3,9,12). Figure 1 details how operant conditioning is used in this intervention. Parent/guardian-child interaction therapy (PCIT) is a specific type of parent management therapy targeted for younger children with the aim of improving the child-parent relationship using play therapy and behavioral modifications (6). Notable programs include Incredible Years and Triple P (3). Parents and guardians should also be encouraged to treat their own mental health concerns if present (11).

Figure 1. Operant conditioning and parent management therapy for ODD and CD (2,3,7,9,12)

Another mode of psychotherapy, especially for CD resulting in severe antisocial behaviors, is multisystemic therapy (MST). MST is an intensive program targeted towards adolescents 12 to 17 years old involving the family, therapists, and community in addressing the roots of severe delinquent behaviors (15,16). MST focuses on working with both the adolescent and guardian. For the youth, MST encourages patient empowerment and development of positive coping skills and support systems within oneís family and community (16,17). MST teaches the parents/guardians skills to help them address the youthís negative behaviors and how they can support their child through adversities in life (17). MST has been shown to reduce antisocial behaviors, incarceration rates, and sex-offending behavior (15,16). Treatment adherence is a large predictive factor of outcomes related to delinquency and incarceration (15). It has also been shown to improve school, work, and home functioning (16). However, MST has not shown better long-term outcomes for mood disorders and substance use (16).

Pharmacotherapy is not the recommended first-line intervention for ODD and CD, nor should it be the sole intervention. However, it can be used to help with symptoms of comorbidities such as ADHD (3,5,9,12) or as an adjunct when psychotherapy alone cannot manage aggressive behaviors (3,9). Methylphenidate and atomoxetine are commonly used for ODD and CD with comorbid ADHD (3,5,11); however, a major concern for giving stimulants to youth with ODD and especially CD is substance misuse or diversion (6). Clonidine and guanfacine may also be effective (3,5,6,11). For aggressive behaviors refractory to psychotherapy, risperidone, lithium, or valproate are possible medication options (2,3,5,6). However, they should be used with caution given the indication is primarily symptom management and because of their potential for serious adverse effects, especially risperidone (2,6).

Prognosis

Most children and teens with ODD do not progress to CD. The majority of behaviors in children with mild-moderate ODD improve with age, indicating a good prognosis (3,5). However, one-fourth to one-third of children with ODD progress to CD (8). This progression is more common in boys and is predicted by dominance of oppositional behaviors over negative affect (2,3,5,6). While family instability is the most significant factor, a diagnosis of ODD before the age of eight and more severe symptoms of ODD in adolescence may also predict the progression of a childís ODD to CD and a poorer prognosis. (2,5,7,8). ADHD and low verbal IQ are also predictors of progression to CD (3,5,7). Factors involved in multiple hospital admissions for destructive behaviors in children with ODD include younger age, and co-occurring suicidal thoughts, or diagnosis of PTSD (13).

There are two developmental pathways for children with conduct disorder: 1) a gradual decline in oppositional behaviors in childhood with a transient increase in delinquent behaviors in adolescence or 2) steadily worsening oppositional and aggressive behaviors (2). An earlier onset of CD and a large number of conduct behaviors indicates a worse prognosis such as progression to ASPD (2,6). Children with CD are also at increased risk for substance use at an early age and subsequent SUD (2,3,6,8). Adolescents with CD are also at increased risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts even when adjusting for psychiatric comorbidities (14).

No matter what a childís current behaviors are or their prognosis, it is important to be patient, compassionate, and honest when addressing and managing ODD and CD. Understanding the complex development of ODD and CD and the multiple interventions to manage them can help to decrease the stigma around these conditions and prevent children with ODD and CD from harming themselves and others.

Questions

1. What is a feature of conduct disorder that differentiates its presentation from oppositional defiant disorder?

a. Verbal, overt, reactive aggression

b. Behaviors persist for 6 months or longer

c. Physical harm towards others

d. Prevalence decreases in college-age individuals

2. Which of the following statements is true about the etiology of ODD and CD?

a. Genetics account for about 25% of the clinical presentation

b. The etiology of ODD and CD is purely psychological

c. ODD and CD are more prevalent in higher SES communities

d. Harsh, inconsistent parenting and poor family structure play a significant role in the development of ODD and CD

3. Which of the following must be considered when assessing for ODD or CD in the clinic?

a. Assessing for learning disabilities

b. Detailed neurological exam

c. Labs to rule out other conditions

d. A detailed history taken solely from the parent/guardian

4. What is the first-line intervention for children with ODD and CD?

a. Pharmacotherapy

b. Parent management therapy

c. School-based interventions

d. Treating comorbidities (e.g., ADHD)

5. True or false: the majority of children with ODD progress to developing CD.

References

1. Matthys W, Lochman JE. Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder in Childhood. Second edition, 2017. Wiley Blackwell, United Kingdom.

2. Connor DF. Chapter 46. Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Children and Adolescents. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P (eds). Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, tenth edition, 2017. Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia. pp:8178-8212

3. Aggarwal A, Marwaha R. Oppositional Defiant Disorder. [Updated 2022 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557443/

4. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed., American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

5. Welsh R, Swope M. Chapter 8. Behavioral Disorders in Children. In: South-Paul JE, Matheny SC, Lewis EL (eds). Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Family Medicine, 5th edition, 2020. McGraw Hill, New York. pp: 76-81

6. LaLonde MM, Newcom JH. Chapter 35. Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder. In: Ebert MH, Leckman JF, Petrakis IL (eds). Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Psychiatry, 3rd edition, 2019. McGraw Hill, New York. pp: 490-508.

7. Mohan L, Yilanli M, Ray S. Conduct Disorder. [Updated 2022 May 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470238/

8. Eskander N. The Psychosocial Outcome of Conduct and Oppositional Defiant Disorder in Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9521.

9. Konrad K, Kohls G, Baumann S, et al. Sex differences in psychiatric comorbidity and clinical presentation in youths with conduct disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63(2):218-228. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13428

10. Deters RK, Naaijen J, Rosa M, et al. Executive functioning and emotion regulation in youth with oppositional defiant disorder and/or conduct disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(7):539-551. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2020.1747114

11. Lillig M. Conduct Disorder: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(10):584-592.

12. Steiner H, Remsing L. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(1):126-141.

13. Boekamp JR, Liu RT, Martin SE, et al. Predictors of Partial Hospital Readmission for Young Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2017;49(4):505-511. doi: 10.1007/s10578-017-0770-8

14. Wei HT, Lan WH, Hsu JW, et al. Risk of Suicide Attempt among Adolescents with Conduct Disorder: A Longitudinal Follow-up Study. J Pediatr. 2016;177:292-296. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.06.057

15. Tan JX, Fajardo MLR. Efficacy of multisystemic therapy in youths aged 10-17 with severe antisocial behavior and emotional disorders: systematic review. Lond J Prim Care. 2017;9(6):95-103. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2017.1362713

16. Multisystemic Therapy (MST) https://youth.gov/content/multisystemic-therapy-mst. Accessed July 6, 2022.

17. Multisystemic Therapy (MST), California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/multisystemic-therapy/detailed#:~:text=Multisystemic%20Therapy%20(MST)%20is%20an,out%2Dof%2Dhome%20placements. Reviewed 2021. Accessed July 6, 2022.

Answers to questions

1.c, 2.d, 3.a, 4.b. 5.False- the majority of children have mild-moderate ODD, in which behaviors typically improve with age.