On January 20th, the John Young Museum of Art hosted “Te Wa: Experimental Looking Lab with Jack Gray.” The workshop was support by the Student Activity and Program Fee Board (SAPFB) and hosted over fifty University of Hawai’i students, staff, and community members. This short paper was written as an assignment for Art Museums and Preservation Practices (ART 400B) by Chelsea Shimabukuro a third year undergraduate student in Art History at the University of Hawai’i, Mānoa.

I was pleasantly surprised at guest speaker Jack Gray’s approach to the idea of “Practices of Looking” during his workshop entitled “Te Wa: Experimental Looking Lab.” Rather than focusing just on “looking” he introduced the concept of perception as relating to the surrounding space that we, the audience and participants inhabited as we took part in a series of exercises that utilized the majority of our senses.

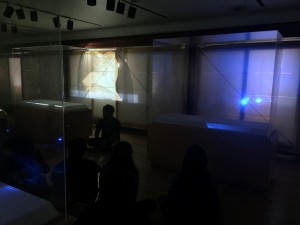

In the first installment in the Commons Gallery, I have to admit that I was at first perplexed and a bit uncomfortable. Removing my shoes outside of my home defies social norms, let alone sitting with many other people in such a small space so close together. Here, the element of tactile sensation, touch, was just as, or more important than, the arbitrary and more passive act of watching or seeing. By seating us in an enclosed space and asking us to remove our shoes, our guest and the performer put us into a scenario in which we needed to become more intimate with the floor, the walls and the space bounded by them; this had the added effect of forcing us to confront her movements and disregard of personal space. The pencils were a hallmark of the intersection between the senses; touching the points to the otherwise blank paper impelled us to make visual marks while maintaining contact with her.

The second installment, in the grassy area in front of JYMA, promoted the role of sound in our participation. Since we were outside, we had to work more to block out the background noise to be able to hear Jack speak, as well as to communicate with each other in what I’ll call the “seeing-eye” exercise, relying on our ears and our feet to tell us where we were. Vision played more of a role when we worked cooperatively, to show our partners what path they took, and when we collectively walked in a straight line; space in relation to each other and the ground.

My favorite installment was the last one, inside the museum, where sound, space and our numbers combined. Here, vision and touch did not dominate as they did in the previous installments. We all had to rely on our ears to listen to Jack and to synchronize our voices to sing and create a circulation of resonance within the enclosed area. This time, perception was guided by collective sound as relating to an interior, enclosed space and recalling other, bigger spaces.