University of Hawai'i at Manoa • William S. Richardson School of Law

ELP Colloquia Series

The William S. Richardson School of Law Environmental Law Program (ELP) is pleased to sponsor an ongoing Environmental Law Colloquia Series. This series brings leading environmental law scholars to the School of Law to discuss their research and perspectives on current environmental issues.

Spring 2004

Madelyn D`Enbeau, Deputy Corporation Counsel, County of Maui

Alan Murakami, The Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation

Jon Van Dyke, Professor, William S. Richardson School of Law

Fall 2003

Lisa Munger, Partner, Goodsill, Anderson, Quinn & Stifel

Paul Achitoff, EarthJustice, Honolulu Office

Spring 2003

Patrick Parenteau, Vermont Law School

Marsha Green, Ocean Mammal Institute

Eudora Iris Lee, Environmental Justice Director for the United Church of Christ

Mike Walker, Environmental Protection Agency, Washington D.C.

Professor David Firestone, Vermont Law School

Fall 2002

Professor Stephen E. Roady, EarthJustice, Washington, D.C.

Spring 2002

Cherie P. Shanteau, Esq., Senior Mediator/Program Manager, U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution, Tucson, Arizona

Professor Howard Latin, International Environmental Law Professor, Rutgers School of Law at Newark, New Jersey

Spring 2001

Professor Alison Rieser, University of Maine School of Law, Portland, Maine

Professor Dan Tarlock, Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, Illinois

Professor James Salzman, American University, Washington, D.C.

Spring 2004 Series

“Land Use Practice After RLUIPA: Special Permits for Religious Use”

Madelyn D'Enbeau, Deputy Corporation Counsel, County of Maui

(April 27, 2004)

D’Enbeau explained that churches are generally concerned with the financial burden of complying with zoning and land use restrictions. |

|

| While zoning plans typically designate specific areas where churches may develop as a legitimate exercise of police power for the health, safety and welfare of citizens, limiting land use for churches presents a special challenge because of historical separation of church and state. The First Amendment prohibits Congress from making any law “respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” A complex doctrine has since evolved, partially because of the wide range of conceivable interpretations for key terms of the clause. The landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court in Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 177, 2 L.Ed. 60, gave the Supreme Court authority to review Constitutional issues. In Reynolds v. United States, 98 US 145, 162 (1879), the Court ruled that a law limiting a religious exercise must have a rational basis for its enactment. This standard is still the law today, except for cases regarding employment benefits for terminations founded on religiously motivated behavior and cases involving hybrid rights (IE: rights of parents to educate their children according to their religious beliefs). For these types of cases alone, the strict scrutiny standard exists. However, after receiving pressure to protect religious freedoms, Congress, in November 1993, passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to reinstate the compelling interest test (the strict scrutiny standard) for application in all cases where free exercise of religion is substantially burdened. Soon after, the Supreme Court invalidated RFRA as it applied to the states, ruling that RFRA contradicted vital principles necessary to maintain separation of powers and the federal balance, and freed religious exemptions from all conceivable civic duties. The Court ruled that a law which is neutral and of general applicability need not be justified by a compelling governmental interest even if the law has the incidental effect of burdening a particular religious practice. Three years later, Congress passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA). RLUIPA warrants litigation in cases 1) that involve federally funded programs or activities, 2) where there is a substantial burden on commerce with foreign nations, among states, or with Native American tribes, 3) or where there is a system of land use regulations involving individualized assessments of the proposed uses for the property. Under RLUIPA, the religious person or entity has the burden of proving that the governmental action “substantially” burdens religious exercise. The Seventh, Ninth and Eleventh Circuits have recently issued varying opinions on the “substantial burden” requirement. A recent Maui case,

Hale O Kaula Church v. County of Maui, reveals a possible discrimination

problem with RLUIPA. A religious organization called Hale O Kaula

applied for a special use permit to build a church on agricultural

land in Kula, Maui. The Maui County Planning Commission denied the

permit. The group, represented by D.C.’s Beckett Foundation,

filed suit in federal court against County and individual Commission

members, claiming that their religious beliefs, which involve farming

the land, require building on agricultural land. The court granted

the county’s motion for summary judgment, but only after the

court initially rejected the county’s motion for legislative

immunity on the grounds that review of a conditional use permit

application is ad hoc rather than legislative. The court later dismissed

the commissioners on quasi judicial immunity grounds. The case is

now in settlement mode and, according to D’Enbeau, the Planning

Commission will probably consider the application again in November

of 2004 after additional evidence is presented to the hearing officer.

D’Enbeau commented that allowing a church to locate on agricultural land because of a belief and denying another religious group without that belief would be a form of discrimination based on religious doctrine. Prior to RLUIPA, most federal courts held that “religious exercise” must be a central tenant of an established faith; and that particular locations and buildings are not protected. RLUIPA states that the term “religious exercise” includes any exercise of religion, whether or not compelled by or central to a system of religious belief; and that the use, conversion or building of real property for the purpose of religious exercise shall be considered to be religious exercise of the person or entity that uses or intends to use the property for that purpose. D’Enbeau explained that a process that allows for individual assessments creates a subtext for racial/religious exclusion. Decisions could secretly be made on impermissible grounds, and this possibility raises the issue of how necessary the process is. D’Enbeau pointed out that the RLUIPA “any exercise” clause has, in one instance, been stretched as far as the creation of a church as a venue for rock and roll concerts. In an environmental context, land use entitlements are very difficult to come by and there is the possibility of RLUIPA abuse by people who want to get on the fast track to an entitlement. Additionally, D’Enbeau said that, because the government is telling citizens what they can do on church land, the separation between church and state has been violated. As there have been over fifty state and federal court decisions since Congress enacted RLUIPA, D’Enbeau predicts that the Supreme Court will soon clarify the “free exercise” and “establish” clauses of the First Amendment. |

|

“Hawaiians and the Environment: Legal and Political Challenges.”

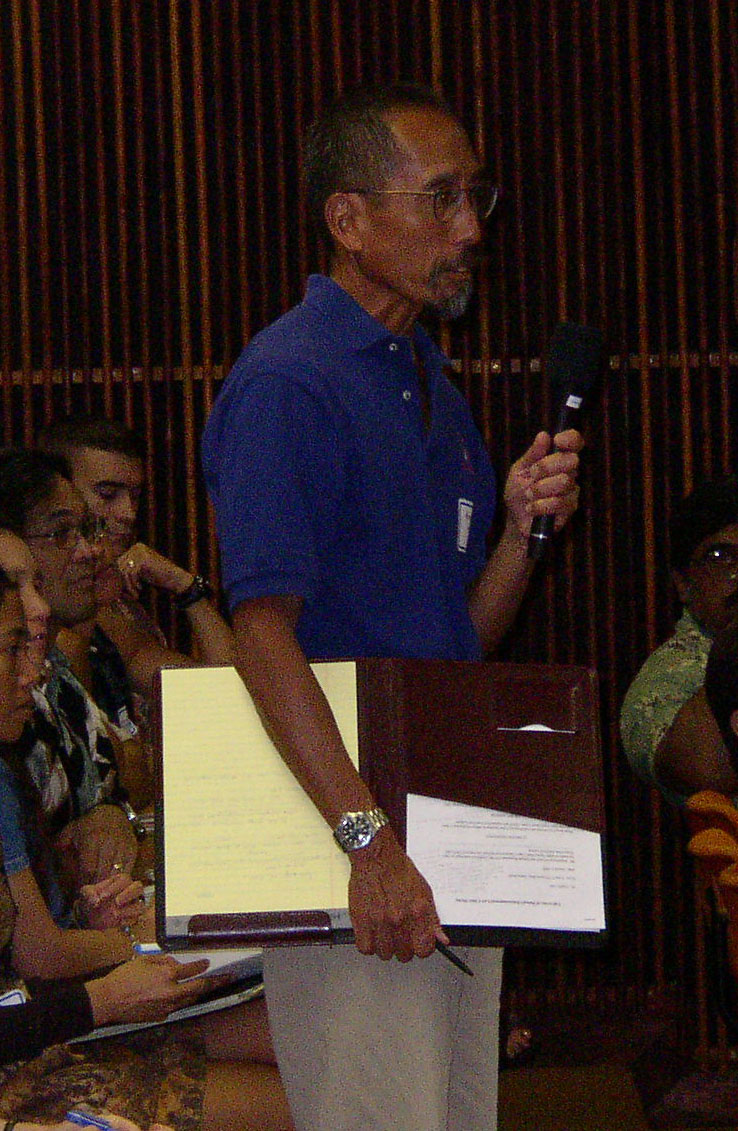

Alan Murakami, The Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation

(Tuesday, March 16, 2004)

Alan Murakami discusses legal issues related to native Hawaiian culture and the environment. |

On Tuesday, March 16, Alan Murakami of the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation shared part of his extensive knowledge on Hawaii’s culture and environment with students and guests of Environmental Law Program. Murakami, introduced by Professor Casey Jarman as the “quintessential public interest lawyer,” has been director of litigation at NHLC for the last 17 years. Named in the Hawaii’s Star Bulletin as among “10 people to make a difference in 2003”, Murakami is widely recognized as a top legal expert on water and land resource issues in Hawaii. In his talk, “Hawaiians and the Environment,” Murakami depicted how Hawaii’s environmental law collides with real-world economics and politics. Murakami set forth two paradigms for development in Hawaii: development accomplished in harmony with culture and tradition in Hawaii and development pursued without respect to culture and environment. He asserted that although Hawaii law is developed to protect and preserve culture and environment, economic and political pressures surrounding development often conflict with the law when development is out of harmony with these values. |

Murakami demonstrated that Hawaiian tradition and culture have been and are at the foundation of Hawaii’s legal system since the transition from oral to written law in Hawaii. For example, early kingdom water law was intended to correct abuses of land by landowners. Thus, early water law was designed to preclude agents monopolizing all of the water from being enriched at the expense of lower classes. This protected the auwai system of irrigation for taro growing, which was premised on freely-flowing stream water and its timely application to fields.

Subsequent Hawaii laws carried forth this intent. The Kuleana Act of 1850 ensured tenants’ rights by recognizing that, without water, land value was significantly reduced. Today, this same act is embodied in Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 7-1.

Case law further delineated protection of cultural environmental rights to water. McBryde provided limits for Mahele grants of title to water. The court restricted water use by sugarcane and pineapple plantations and clarified that the ownership of water remained in the public good. In Robinson v. Ariyoshi, the court held that by sovereign reservation a public trust could be imposed on all waters. In the recent Waiahole Ditch case, a dispute over water formerly used by a sugar plantation, the Hawaii Supreme Court, in a reaffirmation of earlier cases, recognized that the enforcement of native Hawaiian rights is a public trust purpose.

Hawaiian law embodies the

intent set forth by kingdom law to protect culture and environment. Even

what appeared to be the anomalous recognition of a right to the fisheries

in Hawaii’s property law early in the 20th century has been acknowledged

by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Holmes to be a property right, which, if

sanctioned by legislation, he affirmed as valid law. HRS §1-1 declared

English common law to be Hawaiian common law except for that fixed by

judicial precedent or established by Hawaiian usage.

Art. XI §1 of Hawaii’s Constitution affirms that for the benefit

of present and future generations, Hawaii shall preserve and protect resources

in the interest of conservation and self-sufficiency of state. In addition,

Art XII §7 provides that the state shall protect and reaffirm rights

traditionally exercised for religious, cultural, and subsistence purposes.

The Hawaii Supreme Court has regularly reaffirmed these rights and recognizes

the fundamental need to protect them as part of the public trust.

Murakami provided examples of development pursued without respect to culture and environment, which predictably resulted in catastrophic consequences. Cultural rights such as traditional subsistence gathering and fishing often depend on the environment and have been managed over centuries by Hawaiians. In more modern times, developers have ignored culture and tradition by desecrating cultural resources, preventing access to beaches and polluting fishing waters.

Murakami’s most dramatic examples involved the development polluting fishing waters. In Hulopoe Bay, Lanai, a golf course was constructed next to the ocean. Engineers promised they would prevent soil erosion and that their plastic silt fences would hold back the soil. However, in that instance, a small irrigation line broke, the fences failed and thick mud traveled into the ocean, staining rocks that left evidence of these failed promises. In the formerly pristine Hulopoe Bay, at least ten dump truck loads of mud entered the ocean. Similarly, on the Kona Coast of Hawaii, the city engineer exempted golf course developers from an ordinance establishing a 20-acre at a time maximum development restriction. As a result, erosion caused significant soil runoff into Class AA waters off Hokulia on two occasions.

In addition to erosion, the diversion of freshwater streams along the East Maui coast, and the digging of ditches and drilling of wells has negatively impacted taro farming dependent and marine life dependent on that same water. These diversions have upset the fragile balance of the fish food pyramid. According to Murakami, the plain lesson is that developers “shouldn’t play with mother nature.”

Murakami also talked about the disrespect shown by the Hokulia developer for ancient Hawaiian burial sites. Exposed gravesites left poorly protected by plastic fences and tarps failed and ancestral bones washed away during torrential downpours. Archaeologists only discovered a mass burial of what appeared to be hundreds of potential burial remains after bulldozing for a golf course. Due to the failure to accurately map burial lava tubes, the developer went forward nonetheless and built its 7th fairway over a burial tube. In the same development, the State Historic Preservation Division of the Department of Land and Natural Resources refused to protect the burial site of a grandmother of Queen Liliokalani by authorizing the developer to use about one-third of the mass burial site on Pu’u, Ohau unprotected. In another instance, the developer removed historic Alaloa stones without permission by the SHPD to conform to the design of the 16th fairway of the golf course until Third Circuit Judge Ibarra ordered the developer to restore it.

Murakami concluded with optimism, emphasizing that although development continues to ignore culture and tradition at the risk of Hawaiian culture and nature, development in harmony with these values is possible and can be accomplished in Hawaii.

"The Wai`ola Water Rights Decision--Protecting the Rights to Water of the Native Hawaiian People"

Jon Van Dyke, Professor, William S. Richardson School of Law

(February

19, 2004)

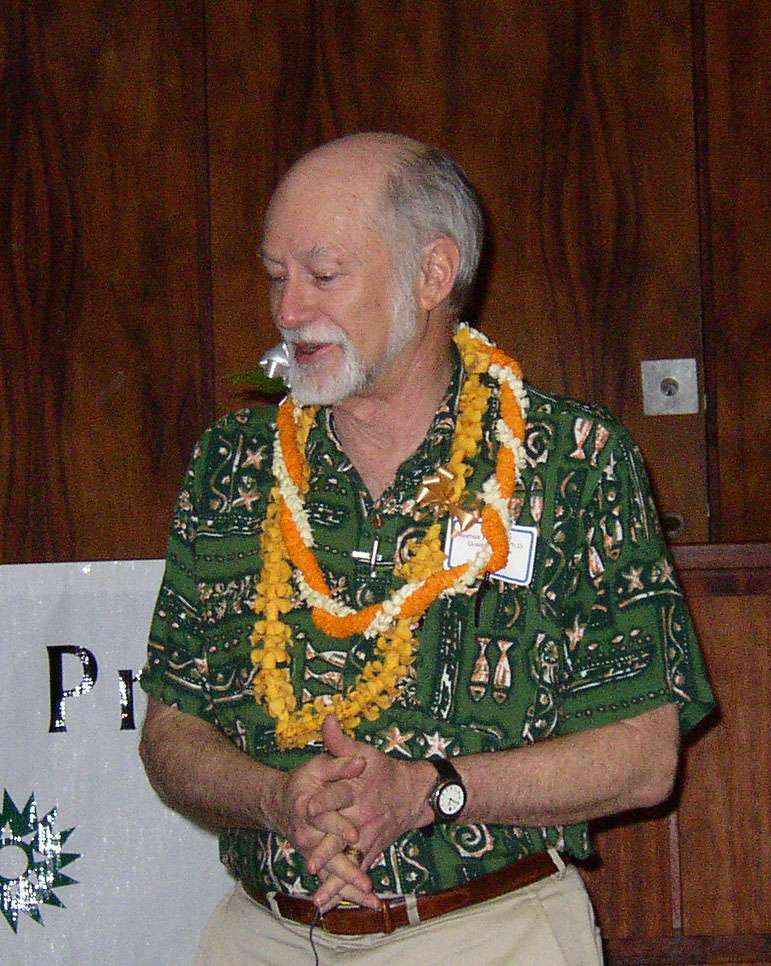

On February 19, 2004, the Environmental Law Program was pleased to have

Professor Jon Van Dyke make a presentation on the Hawai`i Supreme Court’s

recent decision in Wai`ola O Molokai (2004)—an important water rights

victory for Native Hawaiians on Moloka`i. Professor Van Dyke served as

counsel for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (“OHA”) in the

Wai`ola O Molokai case and has also been assisting in the pending companion

case, Kukui (Molokai) Inc.

Professor Van Dyke explained

that the entire island of Moloka`i was designated as a Water Management

Area in 1992. This classification requires all water users to register

their water uses and to seek permission from the Commission on Water Resources

Management (“Water Commission”) for any new uses of water.

The applicant in the case, Molokai Ranch, owns Wai`ola O Molokai, Inc,

as well as approximately 40% of land on Moloka`i. OHA contested plans

by Molokai Ranch developers to build a new well at Kamiloloa that would

draw 1.25 million gallons of water a day (“mg/d”) from the

Kualapu`u aquifer system.

Four groups joined as interveners in the case to help protect the water

rights of Moloka`i homesteaders: OHA, The Department of Hawaiian Home

Lands (“DHHL”), Native Hawaiians represented by EarthJustice,

and Native Hawaiians represented by the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation.

The Wai`ola O Molokai Decision

“MR–Wai`ola

was obligated to demonstrate affirmatively that

the proposed well would not affect native Hawaiians’ rights.”

~ Wai’ola O Molokai (2004)

After reviewing the Water Commission’s decision, the Hawai`i Supreme Court remanded the case back to the Water Commission for further proceedings on Molokai Ranch’s request to develop a new well in central Molokai. The Hawai`i Supreme Court ruled that the Commission’s decision had “violated DHHL’s reservation rights as guaranteed” by the Hawai`i Constitution, the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, and Hawaii’s Water Code. The Court wrote: “MR-Wai’ola had the burden of establishing…that the proposed use would not interfere with DHHL’s 2.905 [mg/d] reservation of water in the Kualapu`u aquifer system.” The Court held that the Commission had not adequately evaluated whether the new well would interfere with the rights of DHHL to develop water sources for its lands on Molokai in the future; therefore, the Commission “clearly erred” in issuing a water permit to Molokai Ranch.

The Court explained that the “reservation” of 2.905 mg/d that had previously been granted to DHHL was a “public trust purpose” and “an essential mechanism by which to effectuate the State’s public trust duty” and was thus “entitled to the full panoply of constitutional protections afforded by the other public trust purposes enunciated by th[e] Court in Waiahole.” The Court’s decision extended the “public trust” protections that it had previously affirmed in the 2000 Waiahole Ditch case to the water rights of the Native Hawaiian people and confirmed that the State’s Water Commission was obligated to ensure that all its actions protected the rights of Native Hawaiians. Reconfirming that Native Hawaiians are in a special category, the Court’s ruling stated: “We have consistently recognized the heightened duty of care owed to the native Hawaiians.”

Professor Van Dyke also discussed issues raised in Kukui Molokai Inc., a companion case to Wai`ola O Molokai that is presently before the Hawaii Supreme Court (as of Feb. 19, 2004).

Fall 2003 Series

"Hawaii's Environmental Response Law and Voluntary Response Program: Forging Alliances with Business and the Environment"

Lisa Munger, Partner, Goodsill, Anderson, Quinn, & Stifel

(October 15, 2003)

|

Lisa Munger enthusiastically explains how the Environmental Response Law works. |

U.H. Manoa Zoology Professor Sheila Conant (left) asks Munger a few questions after her presentation. |

The Environmental Law Program continued its Fall Colloquia Series with an insightful presentation by Lisa Woods Munger, a partner at the law firm of Goodsill Anderson Quinn and Stifel. Ms. Munger has practiced in the fields of environmental law, antitrust law and commercial litigation since 1978. To learn more about Lisa Munger and her achievements visit www.goodsill.com. Ms. Munger has been very supportive of the Environmental Law Program and we were honored to have her speak to a group of students, professors, and community members.

She began the Colloquium by posing the question “How can you join the business community in Hawaii and still do wonderful things for the environment?” Ms. Munger explained that those in the local business community can help the environment by cleaning up sites contaminated with hazardous materials and setting up businesses on these sites. In this way, we can preserve more pristine lands by taking off pressure to develop them.

Ms. Munger explained that Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) to assist in the clean up of these sites. She believes that Hawaii is behind the rest of the country in terms of taking advantage of this law. Nationally more time and money is being spent to clean up areas affected by hazardous waste. In her view more can be done to take advantage of CERCLA. If businesses are not encouraged to use these sites, they will go to undeveloped land to construct their businesses.

She went on to describe how the National Brownsfield Initiative works. It is a program that will release the property owner from future liability under CERCLA. The government monitors the clean-up and gives the property owner a letter stating that the land is sufficiently treated. There are exclusions to this program, it is not available to people who have already bought land, if the site is on the EPA’s National Priority List, or if the property owner is under a court order to clean up the land. The New York Giants Ball Park, Oakland’s Jack London Square, and the San Francisco Presidio are all examples of previous Brownsfields that were cleaned up using this program.

In 1989, the State of Hawaii passed the Environmental Response Law to establish a similar program at the state level. Then in 1997, Hawaii enacted the Voluntary Response Program (VRP) as an amendment to the Hawaii Environmental Response Program. The EPA gave DBEDT over $2 million to administer programs, but according to Ms. Munger, the state is currently working at a snail’s pace and is not taking full advantage of the program. The Office of Hazard Evaluation and Emergency Response administers the VRP and more information can be obtained by visiting their webpage at http://www.hawaii.gov/doh/eh/heer/index.html.

Home Depot was the first company to take advantage of the VRP in Hawaii. This project took previously vacant contaminated land in Iwilei and cleaned it up and developed the land. Ms. Munger explained how this is a good example of how Hawaii business has taken positive steps to enhance Hawaii’s environment.

Dawn Nekoba, 3L

“Environmental Advocacy: Differences, Advantages, and Disadvantages of Working within a Public Interest Organization versus within a Private Law Firm”

Paul Achitoff, Managing Attorney, EarthJustice, Honolulu Office

(September 17, 2003)

|

Paul Achitoff |

The Environmental Law Program was pleased to kick off its Fall Colloquia Series, focusing on environmental challenges facing Hawaii, with a presentation by Paul Achitoff. Achitoff, the Managing Attorney for EarthJustice’s Honolulu Office, spoke to a group of twenty students, professors, and attorneys about his experiences working for both a private firm and public interest organization. Achitoff began his talk with the proposition that the purpose of a private firm is to attract clients and maximize profits, not necessarily to pursue justice; without such bottom-line pressures, a public interest organization, on the other hand, has the freedom to truly advocate for controversial, grass-roots environmental causes. |

Achitoff painted a bleak picture of firm life and its attendant pressures to win and produce income for the firm. Whether a firm takes on a client has much to do with the financial benefits that would follow a victory in court. Achitoff also related his criticism of the pro bono opportunities within firms. While it is true that firm attorneys have the freedom to pursue pro bono work, many don’t have the time. Achitoff said that in many firms, all pro bono must be done on an attorney’s own time. Moreover, in taking on pro bono clients, the firm attorney must be wary of creating a conflict of interest with the rest of the firm’s clients. For that reason, most pro bono work within firms involves family law, not cases that stir up political hostility or threaten the commercial interests of the firm. Pro bono work, therefore, rarely involves environmental advocacy, a political hot button in Hawaii. Inevitably, Achitoff became disillusioned with firm life, the amount of control clients exert over firm attorneys, and their lack of gratitude for his services. He jokingly recalled never receiving a “fruit basket” for his efforts. Although he recognizes that the firm’s clients deserve a defense, he no longer wanted to be the attorney called upon to provide it.

By contrast, work for EarthJustice, a public interest environmental law firm, has energized Achitoff. Within a public interest organization, business principles regarding maximizing profits simply don’t apply. There is no pressure to win or to take on clients who would increase the bottom line. Achitoff is paid a straight salary, commensurate with the amount of years that he has been out of law school. EarthJustice itself is funded through donations and the occasional attorney’s fee award. The organization’s main purpose in advocating for its clients is to defend Hawaii’s environment, not winning or even collecting attorneys’ fees. To that end, the relationship between attorney and client is collaborative and rewarding, in Achitoff’s opinion. EarthJustice most frequently challenges the government for not obeying or enforcing environmental laws. Some of its most important cases involve Clean Water Act violations in Kailua and Honouliuli, as well as the landmark Waiahole Ditch case, which is currently on appeal to the Hawaii Supreme Court for a second time. To emphasize his point that money doesn’t drive EarthJustice’s work, Achitoff made it clear that EarthJustice will not, by statute, collect any attorneys’ fees in the Waiahole Ditch case, even though over a million dollars in work has been invested in that case. EarthJustice’s work revolves around what is at stake, be it a threatened resource, public health, or endangered species, when government fails in its responsibility to the environment. To Achitoff, work within a public interest organization has provided him with more compelling litigation and greater satisfaction than firm life could have.

Spring 2003 Series

Professor Patrick Parenteau, Vermont Law School

(May 7, 2003)

|

Professor Patrick Parenteau |

The Environmental Law Program presented its last colloquium for the academic year on May 7, 2003. The featured speaker was Professor Patrick Parenteau, a professor (and former director of the Environmental Law Center) at Vermont Law School. Professor Parenteau received his B.S. in business administration from Regis College, his J.D. from Creighton University, and his L.L.M. from George Washington University. He has worked as an attorney for the Legal Aid Society of Omaha, the National Wildlife Federation, and the U.S. EPA Region I in Boston. Professor Parenteau’s many specialties include citizens’ suits, the Endangered Species Act, biological diversity, wetlands, and property rights and takings, to name a few. |

Parenteau, who was in Hawaii to deliver the keynote speech at the Seminar Group conference on the Endangered Species Act, took time to share his unusual experiences with law students and faculty from the William S. Richardson School of Law and from the Zoology Department of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Parenteau has been involved in numerous high-profile environmental law cases around the nation.

Parenteau spoke about protecting the whooping crane from the adverse effects of a highway development project, setting wetlands precedent in the Sweedens Swamp/Attleboro Mall case, and defending Native American lands. Not all of his environmental litigation experiences were successful, however. Parenteau was on the briefs for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the Tellico Dam case, which he considers one of the worst environmental law decisions made by the U.S. Supreme Court to date.

In his irrepressible and animated way, Parenteau went on to describe what it was like to be of Special Counsel to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the spotted owl case before the “God Squad” in 1992. He recounted coming face-to-face with a gigantic Oregon logger on the morning of the proceedings. Parenteau, who thought he would be “returned to the earth” at that moment, recalled that the logger had only this to say to him: Where were you ten years ago? His message to the audience was that, in the name of sustainability, both environmentalists and loggers have an interest in saving forests from exploitation.

After his presentation, Parenteau entertained questions from the audience and conversed with students and professors on campus. He spent the rest of the week speaking at the Seminar Group conference and enjoying Hawaii with his family. Photo (from left to right): Andrew McClung, Graduate Student, U.H. Manoa Zoology Department; Adjunct Professor Arnold Lum; Sheila Conant, Chair of U.H. Manoa Zoology Department; Professor Patrick Parenteau; Professor Denise Antolini. |

|

"The Effect of the Navy's Planned Low Frequency Active Sonar (LFAS) on Marine Mammals and the Marine Environment"

Dr. Marsha Green

(March 12, 2003)

The Environmental Law Program was pleased to present a colloquium entitled "The Effect of the Navy's Planned Low Frequency Active Sonar (LFAS) on Marine Mammals and the Marine Environment" by Dr. Marsha Green on March 12, 2003.

ELP Professor Jon Van Dyke introduced Green, a professor of psychology and psychobiology at Albright College. She is the founder of Albright College's Psychobiology and Environmental Psychobiology programs. She is also the founder and president of the Ocean Mammal Institute, a non-profit organization dedicated to conducting ecologically sensitive research on marine mammals and their interactions with humans. Dr. Green has done extensive studies of social vocalizations in humpback whales. Her recent presentations at the Fourteenth Bienniel Meeting of the Society for Marine Mammalogy included "Relationship of Social Vocalizations to Pod Size, Composition and Behavior in the Hawaiian Humpback Whale" and "Singing Humpback Whales Associate with Mothers and Calves." Dr. Green's current research focuses on the effect of noise pollution on marine mammals. She recently co-authored a paper with Whitlow Au, entitled "Acoustic Interaction of Humpback Whales and Whale Watching Boats" in Marine Environmental Research. As a result of this research, she became concerned about the impact of sonar on cetaceans.

Since the late 1980's Dr. Green has been studying the effect of engine noise, as measured in decibels, on the behavior of humpback whales. She discovered that when engine noise reaches 120 dB (the noise level of an average Zodiac boat engine), whales swim away from the source two to three times faster than normal speed. Her research is consistent with that of other researchers who now accept 115-120 dB as the level at which marine mammals display avoidance behavior.

In 1998, Green found out that the Navy was planning to test LFAS off of the Big Island. LFAS produces long-lasting "pings" of noise that measure 240 dB at the source. To a human being, 240 dB is equivalent to the noise one hears standing next to a Saturn 5 rocket upon take-off (assuming that cetacean and human hearing systems are comparable). The Navy had tested LFAS secretly twenty-two times before the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) heard about it. The NRDC suggested that the Navy write an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or face a lawsuit. The Navy then tested the sonar on blue, fin, and gray whales off of California and on humpback whales off of Hawaii in 1997 and 1998. In 1998, Dr. Green sent teams of researchers to Hawaii to study the effect on marine mammals. Results included the separation between mothers and calves and changes in vocalization and migration patterns. To Dr. Green, these changes in behavior reflect a probable harmful impact on mating and feeding.

|

Dr. Marsha Green |

Downplaying these findings, the Navy concluded in its EIS that there was a negligible impact on whales and that it was safe to deploy LFAS. The Navy reasoned that 240 dB will decrease in intensity to 180 dB one kilometer away from the source, and that 180 dB was a safe level of exposure for marine mammals. 180 dB is one million times louder than 120 dB. Curiously, the Navy did not test LFAS at 180 dB. Rather, they tested it at levels no louder than 155 dB. The Navy notes, in a sentence in the EIS appendix, that their lack of empirical data for effects of 155-180 dB on marine mammals presents "an issue." |

After writing the EIS, the Navy applied for a permit from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to deploy LFAS. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), a permit was necessary, because LFAS has the potential to harass, injure, or kill marine mammals. The Navy received that permit in July 2002 and was allowed to deploy LFAS in 75% of the world's oceans. In September 2002, fifteen Cuvier's beaked whales beached themselves on the Canary Islands, where the Navy, with NATO, was conducting sonar testing. According to necropsies of the whales, their deaths were consistent with acoustic trauma. The NRDC went to court to enjoin the use of LFAS, noting that LFAS would surely affect large numbers of marine mammals over a wide geographic area and that the NMFS permit should not have been given. They argued that permits are only allowable if they affect a small group of marine mammals over a limited geographic area. Federal Magistrate Judge Elizabeth LaPorte issued a preliminary injunction in November 2002, allowing the Navy to deploy LFAS only in the one million square miles surrounding the Mariana Islands. The judge's final decision is pending.

In the meantime, other environmental organizations have been successful in battling LFAS in court. Consequently, the Navy and Department of Defense (DOD) have drafted legislative proposals that would give them broad exemptions from many of the nation's environmental laws. Coincidentally, the MMPA is up for reauthorization this year, and the Navy and DOD seek to amend it to weaken the definition of "harassment." Proposed amendments also include broad exemptions for the Navy for specific kinds of testing.

| Dr. Green said that these legislative proposals are currently being fast-tracked through Congress. In addition to proposing amendments to the MMPA, the military is also asking for exemptions from the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. She calls these legislative proposals one of the biggest assaults on our environmental laws in recent memory. The proposals are included in the "Readiness and Range Preservation Initiative" which will probably be a rider on one of the Defense Appropriation Bills, currently in the House and Senate Sub-Committees on Armed Services. |

Emily Gardner, Dr. Marsha Green, and Professor Jon Van Dyke |

The military's main argument is that environmental laws have a detrimental effect on military readiness. Dr. Green disagrees with this, stating that the military is already exempt from these laws during emergencies. EPA Director Christine Todd Whitman and the General Accounting Office have also made similar statements that environmental laws do not impede military readiness in any way.The citizens of Hawaii, she said, wield much influence with regard to these legislative proposals. Of the twenty-five members of Congress that NRDC has singled out as crucial voters on the proposals, three of them-- Senators Inouye and Akaka and Representative Abercrombie-- are from Hawaii. In closing, Dr. Green asked the audience to write or call these legislators to voice their opposition to LFAS and the additional proposed military exemptions from environmental laws.

"How to Get Started on a Career in Environmental Law"

Mike Walker, Environmental Protection Agency

(March 6, 2003)

Mike Walker, the EPA's Senior Enforcement Counsel for the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, spoke with WSRSL students on March 6, 2003 about summer opportunities at the EPA and how to get started on a career in Environmental Law. Mr. Walker runs the EPA Headquarter's summer law clerkship program, which hired sixty-one students during the summer of 2002. Working under the supervision of EPA attorneys, law clerks handle enforcement of laws related to clean air, clean water, and hazardous waste, environmental crimes, international issues, environmental justice, and policy.

In his lively presentation, alternating between theatrical flair and deadpan humor, Mr. Walker spoke about his experiences in law school and beyond, and the qualities that make for a good environmental lawyer. He admitted to yawning through Civil Procedure and Administrative Law, but noted that, ironically, what he learned in these classes forms the basis of his current practice. A good environmental lawyer, he said, is one who is first and foremost "a good lawyer." Mr. Walker advised students to work hard in all of their classes to gain a solid foundation. He impressed upon students the importance of attention to detail by recounting humorous but painful mistakes that lawyers often make in bringing administrative claims. He also recommended that students take advantage of opportunities to gain practical legal expereince through externships, hone their writing skills through participation in law reviews or other publications, network early and often with practicing attorneys, and continue to educate themselves on legal issues that matter to them. When searching for jobs, students should tailor resume information to reflect past experience with environmental work, show a willingness to learn more, and demonstrate a passion and enthusiasm for the environment.

Mr. Walker encouraged students to think broadly and creatively about possible environmental jobs. The EPA itself has numerous job opportunities within each of its ten regional offices; and each office has independent hiring power, so a student interested in working for the EPA should apply to the various regions of interest. The U.S. Government also hires lawyers to handle environmental compliance for the Postal Service, the Department of Energy, and other government agencies. Environmental law comes up in many surprising contexts. He mentioned that corporations like Wal-Mart and Home Depot now have environmental lawyers who are working on issues of security (the vulnerability of their pesticide supplies against the threat of terror, for example), and compliance. In Washington D.C., lawyers for defendant corporations are making millions of dollars doing FIFRA work. The possibilities are limited only by how broadly one is willing to look. Whatever job one chooses, the bottom line, he said, is that the field of environmental law offers an opportunity to do something interesting and meaningful.

From left to right: Professor Casey Jarman, Ranae Doser (1L), Jessica Stabile (1L), Karen Dunai (1L), Mike Walker, Chad Jaffe (1L), Adrienne Iwamoto Suarez (1L), Professor Denise Antolini

"International Environmental Law: Sustainable Development and Third World Countries"

Professor David Firestone, Vermont Law School

(February 14, 2003)

Professor David Firestone of Vermont Law School recently spoke to an audience of William S. Richardson School of Law students, professors, and friends at an Environmental Law Program Colloquium entitled "International Environmental Law: Sustainable Development and Third World Countries."

Professor Firestone founded one of the first Environmental Law programs in the nation in the early 1970s, a time period that ELP Co-Director Professor Denise Antolini referred to in her introduction of Professor Firestone as the "primordial soup" of the environmental movement. He has been teaching at Vermont Law School since 1973, authored Environmental Law for Non-Lawyers, and is currently working on his next book, Global Environmental Law. Professor Firestone has traveled the world extensively to investigate ways to raise environmental awareness in Third World countries.

| Before delving into his current interest in Global Environmental Law, Professor Firestone traced the history of environmental law within the United States. He noted that environmental awareness developed in the 1960s, Congress enacted environmental legislation in the 1970s, and courts interpreted environmental law in the 1980s. The 1990s marked a shift in Congress' approach to regulation from "command-and-control" to "market-based economic incentives" for companies to protect the environment. Firestone commended the relative success of environmental protection in the United States. Though constant vigilance is necesssary on the domestic front, he sees the future challenges of environmental protection emerging most prominently in Third World countries. According to Firestone, "The environment is a global concern. There is no 'us or them.' Pollution know no boundaries; it moves through the air, the water, and the food chain, affecting all of us." |

Professor Firestone |

People can't begin to "indulge" themselves in environmental awareness when the need to survive overshadows all else. The answer, said Firestone, is sustainable development. The U.S. and other nations have come to regard "development" as a dirty word, he stated. For Third World countries, though, sustainable development could offer people a higher standard of living, stability, future security, and the choice to engage in environmental protection.

Firestone concluded his talk by suggesting that the role of the lawyer in a Third World country is to persuade the judiciary to balance the needs of the environment while promoting a better way of life for people. The judiciary provides a necessary check on typically corrupt law-making bodies in Third World countries. He also stressed the necessity of change from within, led by lawyers native to the countries they will serve. |

|

After the colloquium, a First-Year student remarked, "[Professor Firestone] was so inspirational to me, not just in relation to environmental law but to law in general, and beyond that, to thinking in general." The Environmental Law Program was honored to host Professor Firestone for this informative and timely presentation.

Fall 2002 Series

"The New Wave of Ocean Advocacy--Developments in the World of National NGO Marine Law and Policy"

Professor Stephen E. Roady, EarthJustice, Washington, D.C.

(September 18, 2002)| Professor Steve Roady, attorney with Earthjustice in Washington D.C. and long-time Adjunct Professor at American University College of Law, visited the University of Hawaii School of Law during the Fall 2002 semester. Professor Roady taught Domestic Ocean and Coastal Law. Professor Roady, who has litigated several important cases under federal statutes that implement ocean policy, founded the Ocean Law Project (supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts) and served as founding President of Oceana, a non-profit international ocean conservation organization dedicated to protecting life in the sea through public education, advocacy, communications, science and litigation. He also serves on the Advisory Board for the Duke University Marine Laboratory at Duke's Nicholas School of the Environmental and Earth Sciences. His experiences also include serving as counsel to a United States Senator on environmental matters in the Senate Committee on Environmental and Public Works (1989-90) and assisting companies in complying with environmental laws. |

L to R--Professor Roady with Dean Larry Foster (foreground). Sherwood Maynard and Adjunct Professor Arnold Lum (background). |

|

Professor Roady explaining the effects of the summer flounder crash. |

Professor

Roady began his talk about the world's oceans by highlighting a history

of environmental litigation. From 1776 through 1969, virtually all

environmental litigation fell under the common law nuisance doctrine.

One exception was the Rivers and Harbors Act, established in 1899,

which set criminal penalties for pollution. Unfortunately, the act

was never really invoked. In 1969, everything changed as an avalanche

of federal environmental legislation began to be passed--NEPA, CAA,

FWPCA, ESA, CZMA, etc.

Two groups utilized the new regulatory scheme: industry, seeking to challenge the new laws as too onerous, and citizen groups, challenging the ineffectual responses of the agencies responsible for enforcing the new laws. However, virtually none of this litigation had to do with oceans, with one exception--a suit by the Conservatiion Law Foundation (CLF) challenging mandatory reduced fishing effort. Concern over ocean trends was beginning, and it was focused in the arena of overfishing. |

In the 1970s, environmental groups took a closer look at the world's oceans and began working towards their protection utilizing federal statutes through litigation. In 1998, carefully targeted lawsuits were aimed at the federal government to further protect the oceans. The focus was usually on protecting the ocean as habitat for the creatures that lived there, using environmental statutes already in existence and sometimes combining them. The sea turtle bycatch concern (in Hawai'i) fell under the Endangered Species Act. The drop in Steller sea lion population came under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. And, the summer flounder and groundfish drop in numbers (in New England and the Pacific Coast) were related to under-regulation by the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Act.

| Professor Roady recognized the necessity and importance of litigation in the above contexts, but also pointed out how litigation can promote political backlash. One solution is to foster more public education. A number of environmental groups are now devoting more resources to education, realizing a strong need for it. Also, a need exists for more and better science and research. New technologies, such as aquaculture, have some significance for change, but the current methods raise more problems that must be resolved. The technological, political, and legislative schemes must address these concerns. Finally, lawyers must educate themselves on the issues, so that needless and provocatory litigation does not occur without investigating other, perhaps more productive, methods for change and compliance. |

UH Professor Danielle Conway-Jones (in red shirt) asks Professor Roady a question.

|

Spring 2002 Series

"An Introduction to Conflict Resolution"

Cherie P. Shanteau, Esq., Senior Mediator/Program Manager, U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution, Tucson, Arizona

(April 9, 2002)

Cherie P. Shanteau, attorney and mediator/facilitator, joined the U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution in June of 2001. Her responsibilities at the U.S. Institute include collaborative process management; mediation and facilitation services; ADR; and negotiation training relating to attorneys, the courts, the Department of Justice and Attorneys General, and the corporate sector. Her areas of subject matter expertise include property and real estate law, environmental law, Superfund, Western public lands, wilderness issues, grazing and endangered species. Before joining the U.S. Institute, Cherie spent more than 17 years in private practice, including two and one-half years as in-house legal counsel and the Dispute Resolution Manager for a Fortune 500 company owning grocery and drug stores throughout the United States. She has successfully mediated numerous litigated and non-litigated matters, represented clients in mediation, and facilitated several large public disputes. Cherie is on the mediation panels of the American Arbitration Association, U.S. Federal District Court for the District of Utah, Utah State Courts Mediation Program, and the U.S. Postal Service. She has taught mediation, negotiation, conflict resolution and communication skills to law students and other individuals, corporations, and organizations in the United States and Europe.

|

| Cherie received a B.S. in Anthropology from the University of Utah and a Juris Doctor degree from the University of San Francisco School of Law. She was admitted to the Utah State Bar in 1984. She is a member of the Association for Conflict Resolution and the Association for Psychological Type. She is qualified to administer the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Since its inception in 1998 the U.S. Institute has been involved in more than 100 cases and projects in 30 states, two territories, the District of Columbia, border regions of Canada and Mexico, as well as several regional and nationwide projects. The Institute was established by Congress as an independent executive agency to assist parties in resolving environmental, natural resource, and public land conflicts with a federal interest. The purpose of the Institute is to serve as an impartial non-partisan actor providing professional expertise, services, and resources to all parties involved in environmental disputes, regardless of who initiates or pays for assistance. |

From left: Chuck Crumpton (Stanton Clay Chapman Crumpton & Iwamura), Lisa Bail (Goodsill Anderson Quinn & Stifel), Professor Denise Antolini (Co-Director, UH Environmental Law Program), Cherie P. Shanteau (Senior Mediator, US Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution, Tucson, Arizona), Professor Casey Jarman (Co-Director, UH Environmental Law Program), Howard Latin (Visiting Scholar, Rutgers School of Law at Newark) |

The institute provides services such as Conflict Assessment, Process Design, Consultation, Convening, Referral, Consensus Building, Facilitation, Mediation, Training, System Design, Program Development, and Evaluations. The Institute also has a mandate to increase the National Capacity for conflict resolution. The capacity building process includes the creation of a national roster as well as creating a Federal Partnership Program and ECR Participation Program.

The Institute is involved in both ECR and Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). Ms. Shanteau distinguished ADR from ECR in that ADR is a specific from of ECR. ADR is a negotiation assisted by an impartial third party; whereas, ECR encompasses any method of resolving environmental disputes other than adjudication. ECR tends to connote a broad set of processes and issues when applied to the environmental arena.

The benefits of ECR are noted in the results, parties, and resources/time. No single party has complete control over the situation; non-parties must be included in the ultimate solution; and the framework creates a relative balance of power among the parties. Also, relationships are preserved between parties that have or may have an on-going association. Results are tailored by the agencies involved and are promoted by the current political environment. Resources are used more efficiently; for example rather than employing 'dueling experts', joint inquiries are made.

"Fundamental Dilemmas of Environmental Law"

Professor Howard Latin, International Environmental Law Professor, Rutgers School of Law at Newark, New Jersey

(February 19, 2002)

| I. INTRODUCTION

|

Professor

Howard Latin |

Is it possible that most law professors, lawyers, and law students know virtually nothing about Environmental Law (EL) except the tautology that it deals with various aspects of the environment? As a heuristic device to explain why EL is uniquely challenging, this Article identifies five "fundamental dilemmas" that arise from the underlying circumstances, conditions, and values in varied environmental contexts.

II. DILEMMA ONE: MULTIPLICITY OF LEGALLY PROTECTED INTERESTS

EL must recognize and accommodate a broader range of legally protected interests than any other field of law. EL not only encompasses a wider range of legally protected interests than other legal fields, but it is the only field that must deal with legally protected interests that are not exclusively focused on human effects and benefits. The multiplicity, incommensurability, and unquantifiable character of many environmental interests requires legislative policy-makers and administrative officials to balance diverse competing factors under nebulous decisional criteria. The resulting decisions are certain to be controversial whether they seek to include all conflicting environmental, economic, and social interests or to exclude some relevant interests.

III. DILEMMA TWO: INAPPROPRIATE POLITICAL AND TEMPORAL BOUNDARIES

From an environmental viewpoint, the political and legal boundaries created over hundreds of years to serve human needs are inappropriate and often irrational. Most of our geopolitical boundaries were created long before ecology and toxicology were recognized as sciences and these boundaries impose arbitrary jurisdictional barriers that constantly impede effective environmental planning and regulation. The time-frames or temporal boundaries associated with most human activities and institutions are similarly inappropriate for many environmental processes. EL must somehow function despite numerous mismatches between political, legal, temporal, geological, and ecological boundaries.

IV. DILEMMA THREE: THE TRANSITION FROM PERCEIVED ABUNDANCE TO PERCEIVED SCARCITY

For many environmentalists, America is no longer perceived as "the land of plenty." With regard to natural resources depletion and related ecological degradation, proponents of continued natural resources exploitation rightly claim that their livelihoods, homes, communities, businesses, preferred life-styles, and personal autonomy are at stake. Environmental advocates rightly reply that natural resources exploitation activities are destroying irreplaceable ecological features and systems, and current practices will inevitably impose massive long-term social and environmental losses if they are allowed to continue on a non-sustainable basis. Where is the middle ground between these sets of politically powerful arguments?

V. DILEMMA FOUR: PERVASIVE COMPLEXITY AND UNCERTAINTY

In addition to the complicated human and organizational relationships at the core of other legal fields, EL must confront innumerable complexities and uncertainties arising from interactions between human behavior and environmental phenomena. Critical processes, whether systemic or random, at the boundary-lines between natural conditions and human activities, such as global climate change, deforestation, species habitat destruction, and natural resources depletion, typically lack adequate baseline data and adequate scientific understanding. Environmental agencies and reviewing courts must therefore grapple with complicated economic issues, including present and future industry profitability, foreign competition effects, ability to attract capital for investments, and retention of competitive market structures.

VI. DILEMMA FIVE: THE NEED TO REVERSE CENTURIES OF PRO-DEVELOPMENT POLICIES AND PRACTICES EMBEDDED IN AMERICAN LEGAL DOCTRINES

As one prominent EL scholar noted some years ago, EL is inescapably subversive. For centuries, established legal doctrines and practices have promoted development and have failed to protect nature or human satisfactions derived from non-consumptive interactions with nature. The law for centuries provided essentially no legal rights to environmental protection or to ecological sustainability except for the right to buy a tract of land and then not develop it. In recent decades, environmentalists have attained sufficient political influence to adopt thousands of statutes and regulations intended to overturn previous legal impediments to environmental protection. Yet, there can be no doubt that pro-entrepreneurial, pro-development biases are still dominant in the great majority of American legal contexts. EL must therefore continue to challenge the historical, doctrinal, and ideological underpinnings of a legal system that actively encouraged so many environmentally destructive practices to flourish in the past.

VII. CONCLUSION

it must be emphasized that all of these dilemmas complicate environmental decision-making concurrently and continuously. The fundamental dilemmas generate or strongly influence a much larger set of specific legal problems that routinely arise in environmental contexts. The aim of this Article is not only to describe central themes and constraints that unite diverse areas of Environmental Law and to demonstrate that EL is an independent legal field with many fascinating characteristics, but also to show that a better understanding of the fundamental dilemmas of EL can help professors, lawyers, and students involved in other legal fields. To paraphrase Clemenceau's famous dictum about war and generals, Environmental Law is too important a subject to be understood only by EL specialists. Environmental Law is a challenging field worthy of much greater academic recognition and respect than it now receives, and lawyers working in many other legal fields can understand their own subjects better if they expand their knowledge of the multifaceted dimensions and dilemmas of EL.

Spring 2001 Series

"US Fisheries Law: Two Hawai'i Case Studies"Professor Alison Rieser, University of Maine School of Law, Portland, Maine(March 19, 2001)

Professor Rieser explained the role of the National Environmental Policy Act ("NEPA"), which requires the responsible federal agency to complete either an Environmental Assessment or Environmental Impact Statement. She also discussed the role of the Endangered Species Act ("ESA"), which mandates the National Marine Fisheries Service ("NMFS") to determine whether any action which it authorizes, such as a commercial fishery, is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any species listed as endangered or adversely modify that species' habitat. In both of these case studies environmental plaintiffs brought suits before the federal district court in Hawai`i. They both resulted in injunctions of the respective fisheries pending analyses by NMFS required under the ESA and/or NEPA. According to Professor Rieser, NMFS has recently determined that the Hawai`i longline fisheries are likely to jeopardize endangered sea turtles and has recommended the closure of Hawaii's swordfish longline fishery and a two-month closed season on the tuna longline fishery. With respect to the Hawaiian monk seal, Professor Rieser explained that the court had found NMFS to be in violation of its duties under NEPA and enjoined the Northwest Hawaiian Islands lobster fishery. The judge has not yet issued a ruling with respect to the bottomfish fishery. The impact of the litigation on both of these Northwestern Hawaiian Islands fisheries is uncertain; there is also a new Northwest Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve established by President Clinton's Executive Order which may result in a different regulatory scheme for the fisheries operating in the reserve. Professor Rieser acknowledged her gratitude to the Law School and to Professor Casey Jarman whose sabbatical has enabled her to be here. Further, she acknowledged her good fortune to be here in Hawai`i during a time of so much unique activity in marine fisheries law. |

"When Is It Ever Proper to Apply the Public Trust Doctrine to the Allocation of Water? The Waiahole Ditch Case"

Professor Dan Tarlock, Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, Illinois

(February 26 2001)

| Professor Dan Tarlock taught Property Law and Second-Year Seminar at the William S. Richardson School of Law in Spring 2001. He is a Distinguished Professor of Law and the Co-Director of the Program in Environmental and Energy Law at the Chicago-Kent College of Law. He is an internationally recognized expert in environmental law and the law of land and water use. He has published a treatise, Law of Water Rights and Resources, and is a co-author of four casebooks: Water Resource Management, Environmental Law, Land Use Controls, and Environmental Protection: Law and Policy.

|

| Professor Dan Tarlock (center) with Environmental Law Program Professors Jon Van Dyke and Co-Director, Denise Antolini.

|

Professor Tarlock gave his presentation on the Waiahole Ditch Case, which involved a dispute over water rights in Hawai'i. He stated that this case was a very important one with national and international implications and has entered into a universe of significant cases. Professor Tarlock focused his talk on whether the decision in the case was legitimate or not. |

| He also stated that the Waiahole Ditch case is significant because the Hawai'i Supreme Court has integrated the California public trust doctrine in the Hawaiian statutory water regime. The bottom line is that the trust reinforces statutory duties to protect surface and ground water, placing conservation duties on the state. |

Professor Dan Tarlock talks about the Waiahole Ditch case. |

| “Beyond the Smokestack: Environmental Protection in the Service Economy” Professor James Salzman, American University, Washington, D.C.(January 29, 2001) |

|

| Professor James Salzman is a leading international environmental law scholar at the Washington College of Law at American University in Washington, D.C. He received his J.D. from Harvard University and has written numerous articles and books on the subject of environmental law. Professor Salzman gave his speech on the shifting regime to a service based economy and its potential impacts on the environment. He addressed the extent to which service is increasing, the implications for the environment, and its meaning. He pointed out that the Environmental Protection Agency does not look at the service industry because it is thought of as a "clean" industry. He then broke down the universe of services into three categories: smokestack services, cumulative services, and leverage services. |

|

|

|

Professor James Salzman |

| Check back at this site soon for future Colloquia Presentations. |

|

| Request

ELP Brochure or Law School Application / Contact

Information |

|

On

April 27, 2004, Madelyn D’Enbeau, Deputy Corporation Counsel

for the County of Maui and 1977 WSRSL graduate, shared with ELP

guests and members the legal complexities of RLUIPA-governed religious

rights to land use. D’Enbeau first guided her listeners through

a brief history of RLUIPA and how religious rights to land usage

developed. She then discussed constitutional concerns brought to

light by recent RLUIPA litigation in Maui County.

On

April 27, 2004, Madelyn D’Enbeau, Deputy Corporation Counsel

for the County of Maui and 1977 WSRSL graduate, shared with ELP

guests and members the legal complexities of RLUIPA-governed religious

rights to land use. D’Enbeau first guided her listeners through

a brief history of RLUIPA and how religious rights to land usage

developed. She then discussed constitutional concerns brought to

light by recent RLUIPA litigation in Maui County.

Professors David Callies, David Firestone, Denise Antolini, and

Bruce Wilcox (of the UH Medical School).

Professors David Callies, David Firestone, Denise Antolini, and

Bruce Wilcox (of the UH Medical School).