By Alison D. Nugent, Ryan J. Longman, Clay Trauernicht, Mathew P. Lucas, Henry F. Diaz, and Thomas W. Giambelluca. Click here to read the publication.

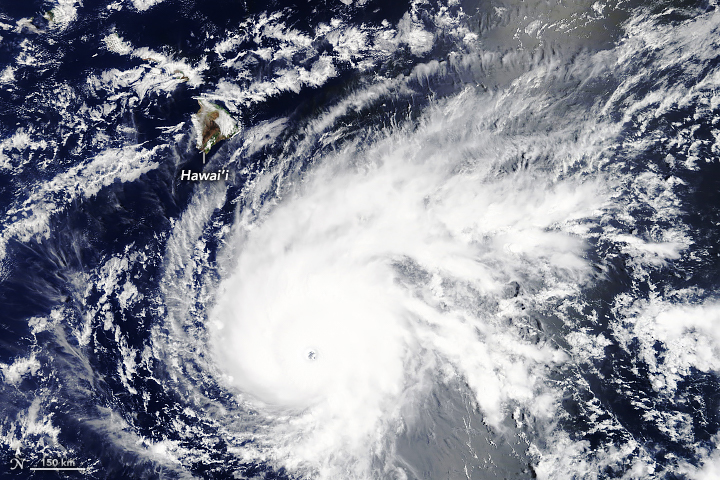

“Hurricane Lane, which struck the Hawaiian islands on 22–25 August 2018, presented a textbook example of the compounding hazards that can be produced by a single storm. Over a four-day period, the island of Hawaiʻi received an average 17 inches of rainfall. One location received 57 inches, making Hurricane Lane the wettest tropical storm ever recorded in the state and the second wettest ever recorded in the US.

At the same time, three wildfires on the island of Maui and one on Oʻahu burned nearly 3,000 acres of abandoned agricultural land. All of these fires occurred on the drier, leeward slopes of the islands, driven by hot summer weather, preexisting drought, and high winds around the periphery of the hurricane.

The simultaneous occurrence of rain-driven flooding and landslides, high-intensity winds, and multiple fires complicated emergency response. These compound hazards highlight the need to improve anticipation and preparation for complex climate- and weather-related phenomena.

In Hawaiʻi, hurricanes rarely make landfall due to persistent vertical wind shear over the islands. When hurricanes occur near Hawaiʻi, however, the geography of the islands can exacerbate the hazards. The nearly 746 miles of coastline make much of the state susceptible to coastal flooding, and the mountainous topography can intensify rainfall and wind speeds. In addition, the steep mountainous terrain can enhance flash flooding and trigger landslides.

The center of Hurricane Lane did not pass closer than 140 miles from the island of Hawaiʻi. Nevertheless, the prolonged, torrential rains associated with the hurricane’s large scale and slow speed resulted in flooding, mudslides, and landslides across many parts of the island and other parts of the state.

Hurricane Lane provides a unique case study of how atmospheric conditions associated with hurricanes can contribute to both record rainfall and increased fire risk at the same time. While heavy rain is a familiar feature of tropical storms, the strong convection near the storm center is also associated with, or perhaps compensated by, descending air around the storm’s periphery. This subsiding air is warm and dry, and together with intense storm-driven winds, it can increase the risk of fire hazard in the periphery of a hurricane, especially if preexisting conditions predispose the area to fire.

On Maui and Oʻahu, nonnative, fire-prone grass- and shrublands accounted for more than 85 percent of the area burned. A previous weather pattern of wet months followed by dry months led to a surplus of dead, dry grass that fueled the fires.

The immediate causes of the Maui fires remain unknown, but the Honolulu Fire Department attributed the Oʻahu fire to arcing from electrical lines caused by high winds. Altogether, more than 100 county firefighters were required to contain and extinguish the blazes. The strong, erratic winds associated with the hurricane grounded helicopters, which are a critical resource for fire suppression in Hawaiʻi’s steep terrain. The deputy fire chief on Maui described firefighting conditions as “some of the most adverse the Maui Fire Department has faced in recent history.”

The Hawaiian islands suffered considerable damage. The wildfires in west Maui destroyed 21 structures and 30 vehicles and forced the evacuation of 100 homes and the relocation of a hurricane shelter. On Hawaiʻi island, severe flooding and landslides led to road closures across the island, and torrential rains damaged 30 businesses and 152 homes and forced more than 100 people to evacuate. Altogether, the hurricane caused one death and an estimated US$250 million in property damage.” (East-West Wire)